| artcornwall | ||

| home | features | exhibitions | profiles | gazetteer | links | archive | ||

eekThe Old Grammar School, Redruth, August-September 2006

The old Grammar school in Redruth was built out of distinctive local stone during the last century, at a time when the town was still one of the most prosperous and influential in Cornwall, situated as it had been in the heart of the tin-mining industry. The school lay disused for several years before being reopened, with all the original fixtures tatty but intact, as artists’ studios last year. ‘eek’ was the first exhibition held at the site. It was an open submission show curated by two artists, Sovay Berriman and Jacqueline Knight, and with the support primarily of Creative Kernow and latterly Cornwall Arts Marketing, it was able to generate a good degree of publicity and interest from the outset.

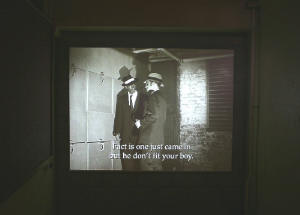

In a darkened side room a black and white film by Mike Cooter, ‘Dead reckoning’ (above) featured deaf actors re-enacting a scene from a film made in the 30s. The scene was set in a morgue, and the actors communicated using sign language, with subtitles providing an ongoing translation. The film was carefully poised between tragedy and comedy, and seemed to comment on the difficulty of pure communication.

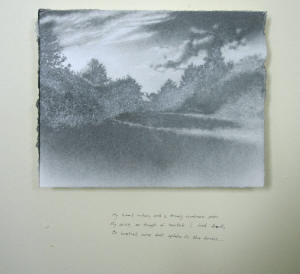

More reticent, and arrayed on two walls of the same space, were immaculate miniature pencil drawings by Barry Thompson (above). These mixed idealised images of the landscape, with depictions of rock singers and guitarists, each with a few lines of 18th century poetry or song lyrics written directly onto the wall of the old school. They were like school-boy graffiti, made into perfect and pristine statements of ambition and longing.

Jane Atkinson

has, for several years, been involved with a labour-intensive project to

map the county of Cornwall by measuring metals and other trace elements

present in its rivers.

In the last room Andrew Currie showed an ensemble of low-fi kinetic sculptures in which objects like ping-pong balls and sand from a local beach were animated by fans of the kind normally used to cool computer towers. (right). Sourced from the local pound shops, yet effortless and hypnotic, these objects had a compelling and magical quality that belied their lowly status. This summer has been a particularly interesting and eventful time in Cornwall. eek was pulled off with swagger and aplomb: certainly matching comparable artist-curated shows in London. There was little attempt by the curators to engage with local traditions of art-making, however, and this was probably a calculated risk to put some distance between the show and the artistic legacy of the county now firmly institutionalised and embodied in Tate St Ives. Instead the show has set a new precedent for Cornwall, and in making a clean break with the past, has suggested new directions for artists working in the county.

Rupert White August 2006

|