|

The Transformed Total: Margaret Mellis’s

Constructions

Michael Bird

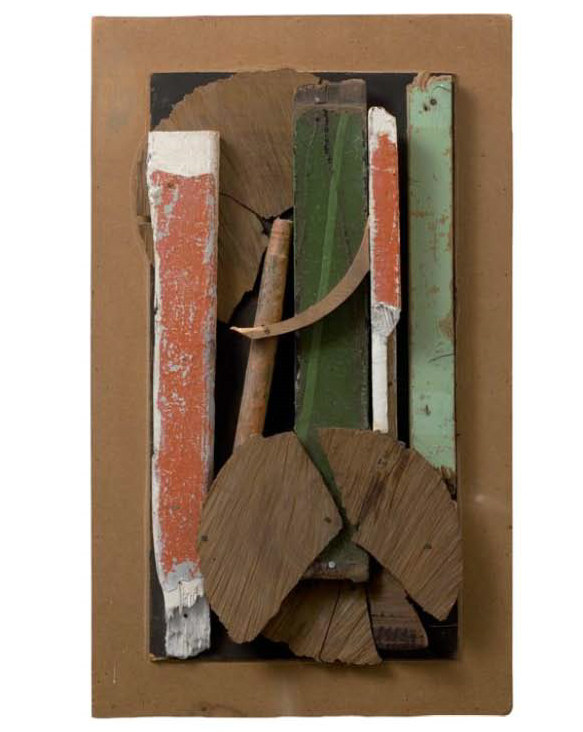

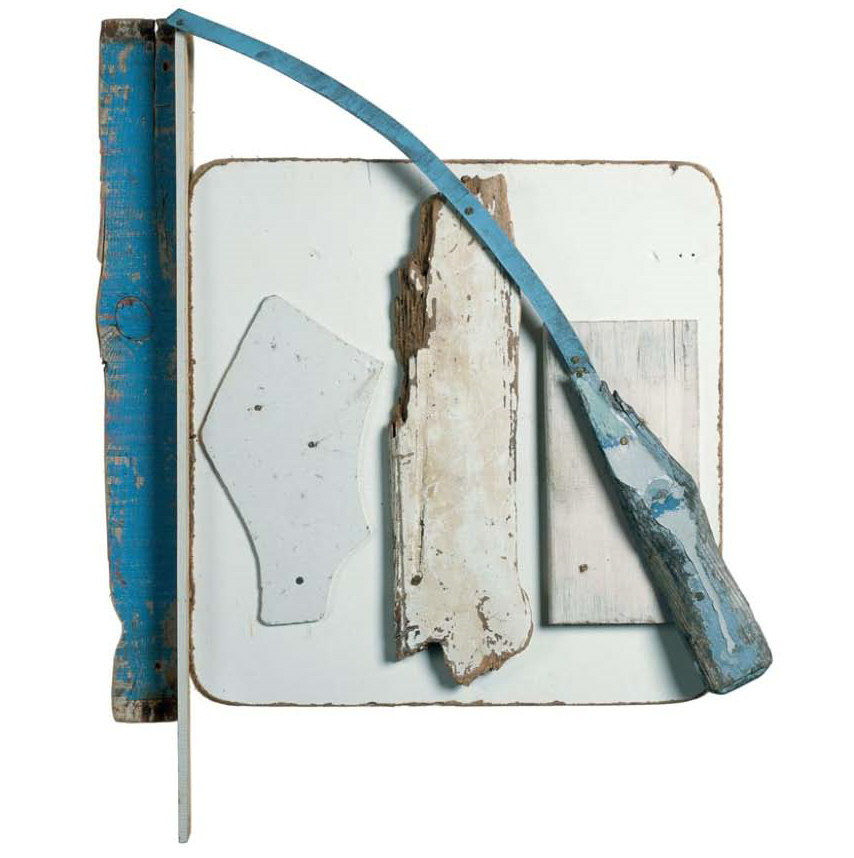

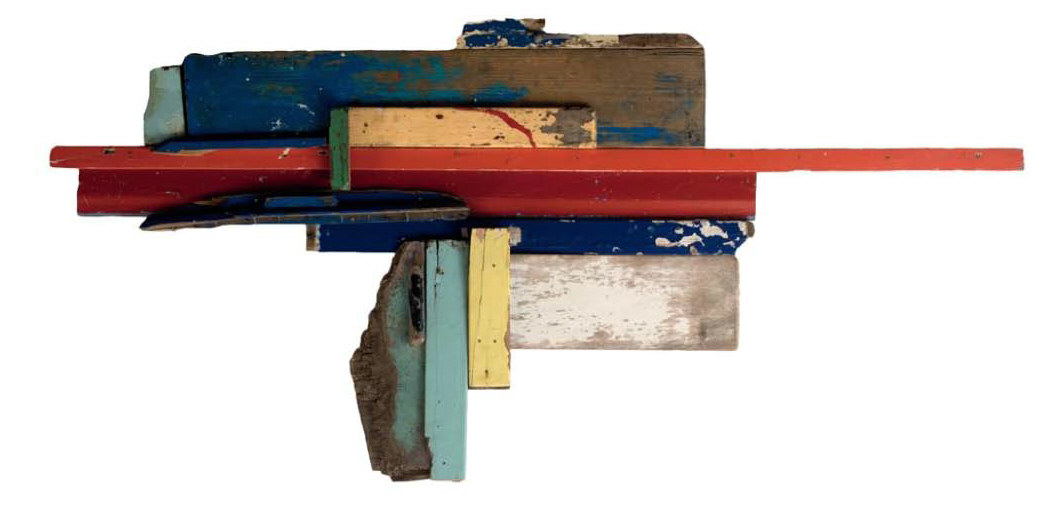

In 1978 Margaret Mellis, then in her mid-sixties, assembled some pieces

of driftwood into an ad hoc sculpture. This was the beginning of what

turned out to be a new phase in her art. Anyone could have picked up

these fragments – wave-worn plywood boards untidily snapped like

indigestible wafers, bust planks and wooden fillets that had once been

painted red, blue or green for some purpose now impossible to ascertain.

Rescued from the tideline dumping ground of leathery wrack and mangled

rope, these scraps of unvalued jetsam were shaped by whatever had

happened to happen to them. Mellis played about, arranging and

rearranging, much as friends often observed her instinctively adjust the

placing of ordinary objects – a bowl on a windowsill, a napkin and knife

on a tabletop – until they ‘looked right’. Screwed into place, the

provisional configuration became a permanent construction that could be

hung on the wall and looked at. No longer spread on the floor to be

accidentally destroyed or thrown back on the woodpile, it had crossed an

invisible line that distinguished those ephemeral still-lifes into which

Mellis conjured her domestic surroundings from the creations of her art.

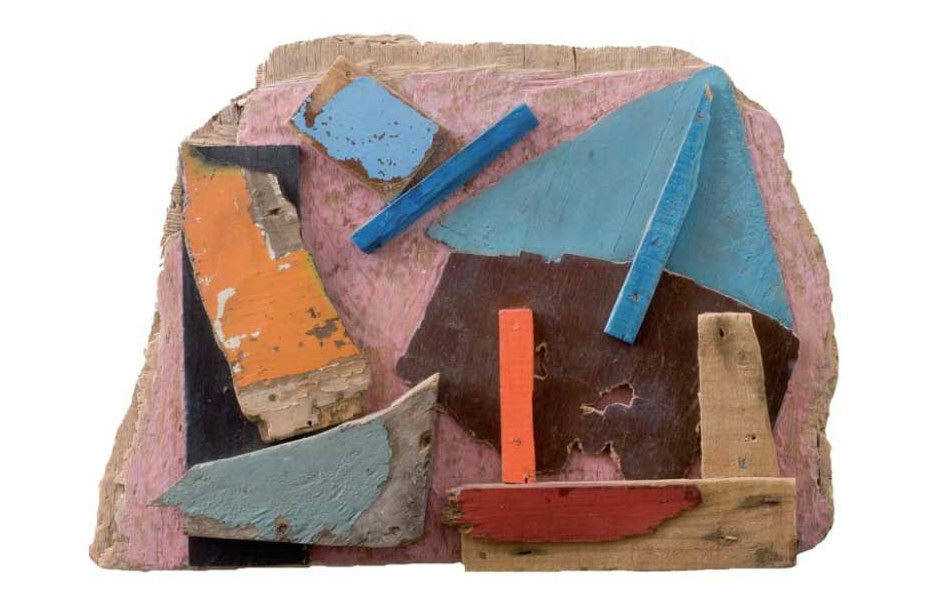

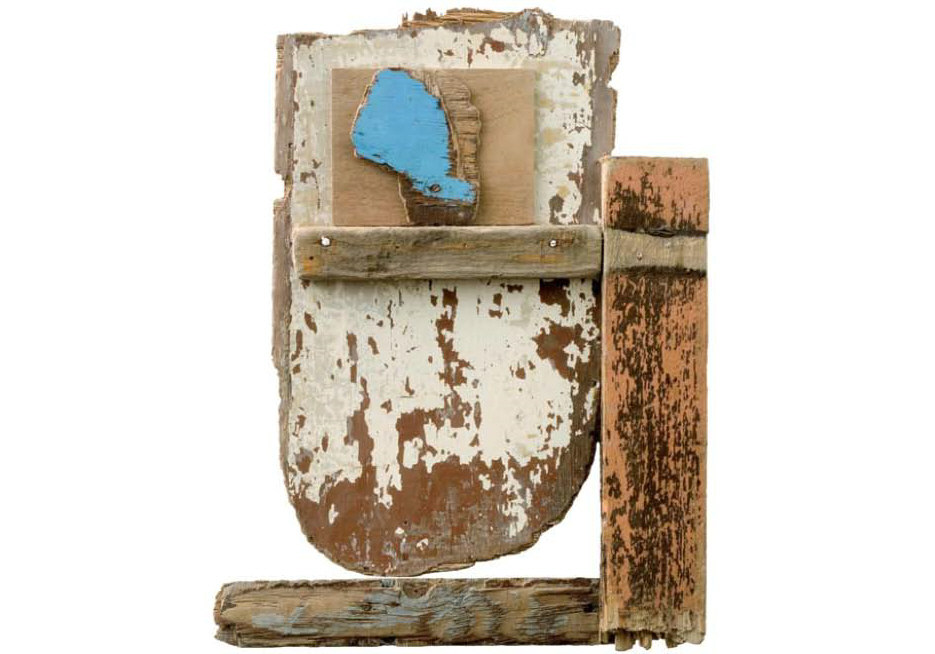

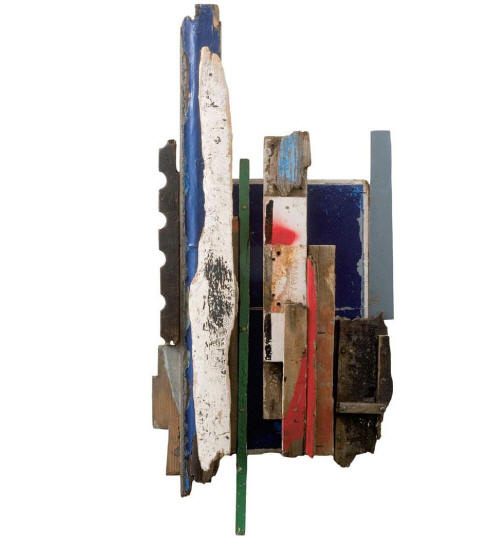

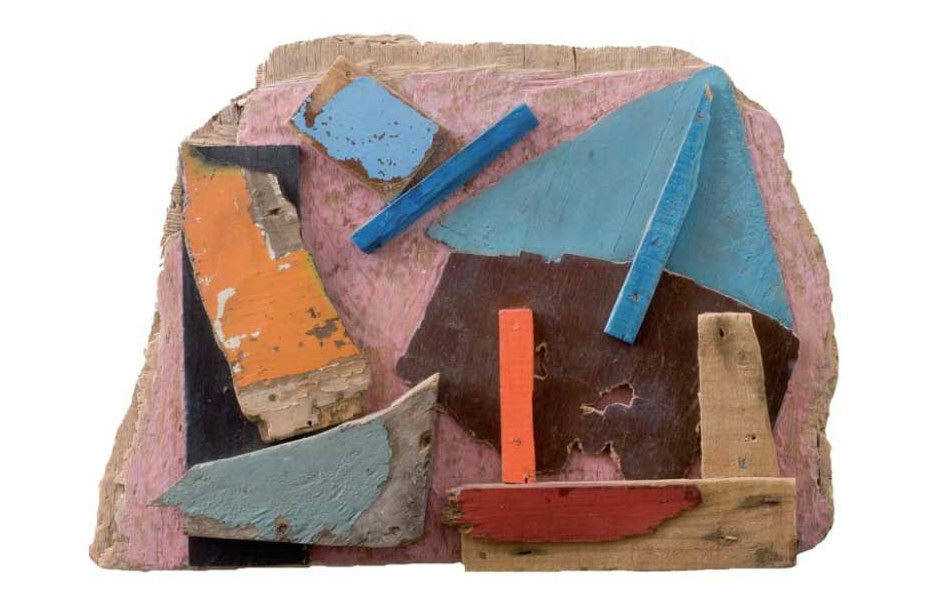

‘F’ 1997 driftwood construction 148 x 145 x 6cm

Adrian Stokes, Venice c.1928

It was almost fifty years earlier that she had started out as a student

painter in the French-influenced mode of her tutors at Edinburgh College

of Art, notably the Scottish landscapist W.G.

Gillies. There followed the semi-obligatory spell Paris in1933, studying

with Gillies’s former mentor André Lhote, whose passion for Cézanne had

by that time evolved into cubistic figure paintings, then further

travels in France, North Africa, Italy and Spain, and another visit to

Paris in summer 1937. Here, at the Exposition Internationale,1 she must

have witnessed the ominously confrontational style of the Nazi German

and Soviet pavilions, and may also have seen Picasso’s Guernica in the

pavilion of the doomed Spanish Republic. She certainly took in an

exhibition of early Cézannes in the newly constructed Palais de Tokyo,

where she got into conversation with a charismatic, well-travelled

English writer of improbably eclectic interests. In retrospect, the

circumstances of this meeting were a mixed augury both for Mellis’s

future relationship with Adrian Stokes (whom she married the following

year) and for her own artistic career. Cézanne was on show as a

latter-day hero of the grand tradition of French painting, but he was

also venerated by the

Marsh Mist 1992 driftwood construction 71 x

55.3cm

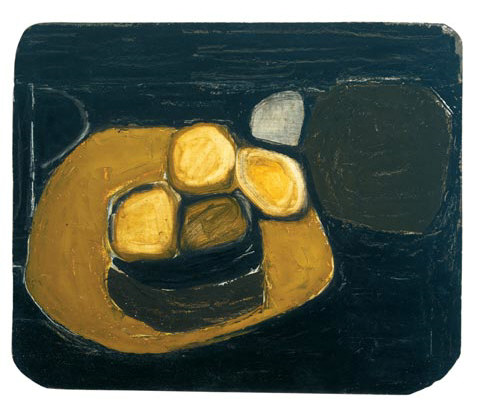

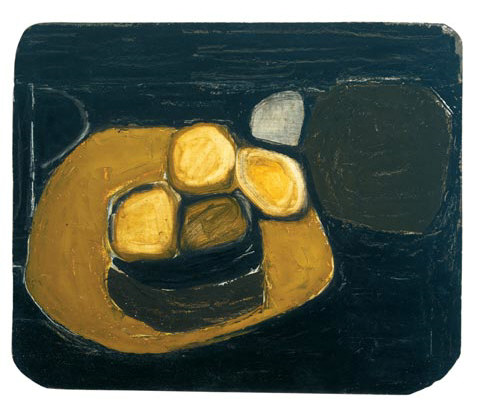

Pots and Fruit c.1960 oil on hardboard 45 x 54cm

avant-garde. It took Stokes some time (and the British art public much

longer) to discover that the gamine young Scottish artist who seemed,

like him, engrossed by classic painterly questions of colour and form,

also had it in her to play a very different kind of game.

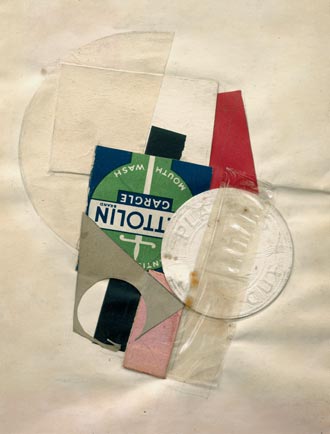

If it was hard to be sure before then, it became clear around 1940 that

Mellis was decidedly not going to spend the rest of her life producing

pleasantly derivative homages to Gillies, Lhote or Cézanne. Now living

in Cornwall, with the war on and, after the birth of her son Telfer in

1940, a child to care for, she nevertheless managed to create her first

wholly distinctive body of work – a sporadic yet somehow confident and

complete series of abstract paper collages that counts among the most

vivid, unusual work to come out of St Ives during the war. Some were

included in a popular 1942 exhibition in London, New Movements in Art

(which in the event proved a false dawn for progressive abstract art in

Britain), but professionally they got Mellis nowhere. Divorce from

Stokes; a new marriage, to the painter Francis Davison (whose own career

seemed to demand precedence from

Collage

with Red Triangle 1940 paper collage 29.5 x 23cm Private Collection

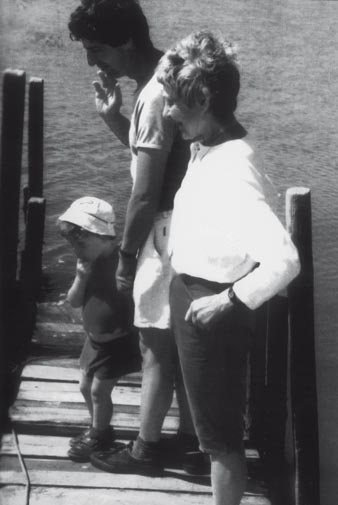

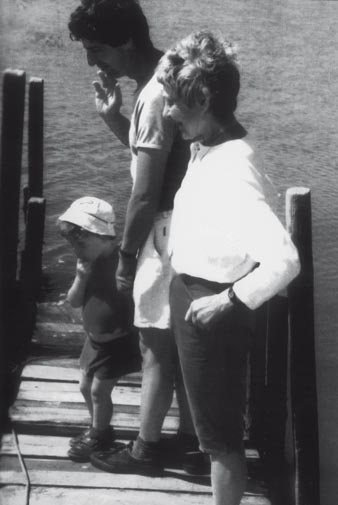

Margaret

Mellis (right) and Francis Davison, Cannes 1948

then on); a move to southern France, well out of the London gallery

orbit – all this cut across a steady career trajectory, although Mellis

continued to work and exhibit. At various times between 1950 and 1980,

she produced abstract paintings in the crypto-figurative postwar

landscape style; spare, intense flower paintings; interestingly shaped

pastel drawings on splayed envelopes; more abstract works, this time in

the flat, hard-edge manner fashionable in the 1960s. A few of these

pieces found their way into public collections. On the whole, though,

Mellis’s loyal critics and collectors belonged to one of those secret

confraternities to whom an artist’s voice speaks clear and compelling

long before it gets pumped through the PA system of a public reputation.

I don’t know that in 1978 even they would have guessed that her next

body of work – the largest, longest sustained and, in her view, the best

of her career 2 – was about to emerge from a stack of driftwood that fed

the fire in the cottage in Southwold, Suffolk, to which she and Davison

had moved two years earlier.

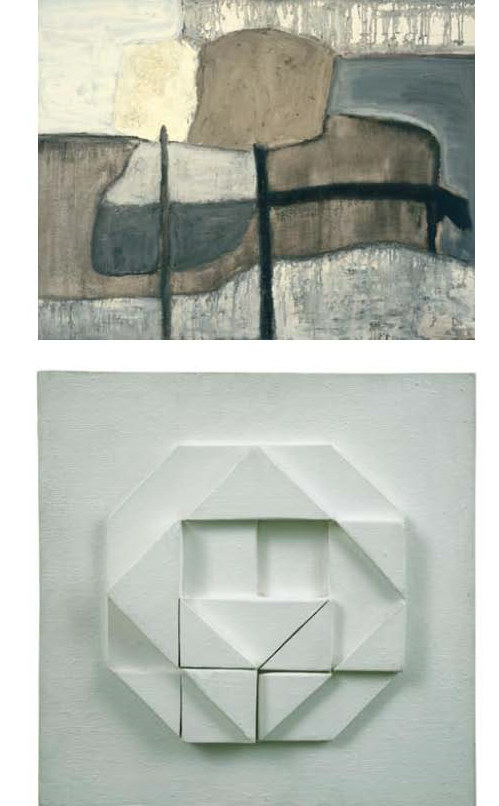

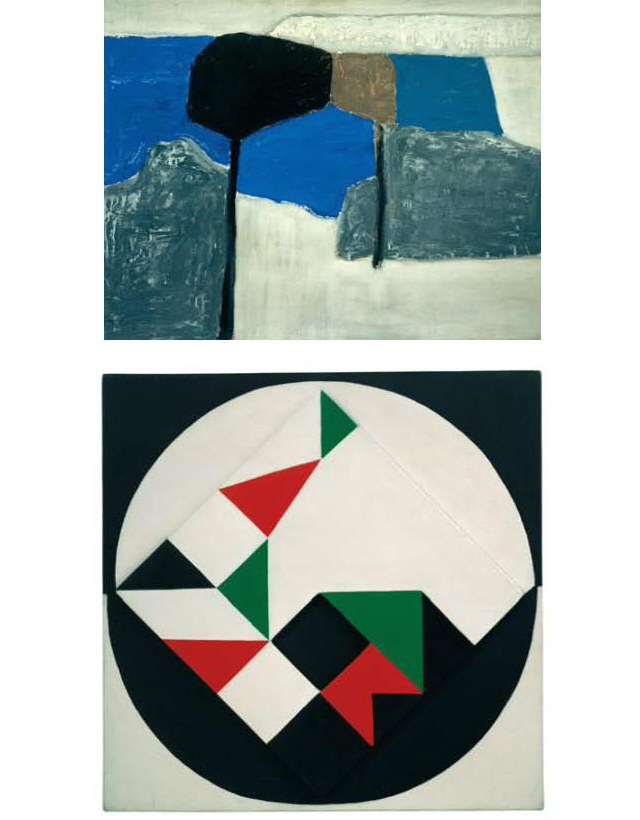

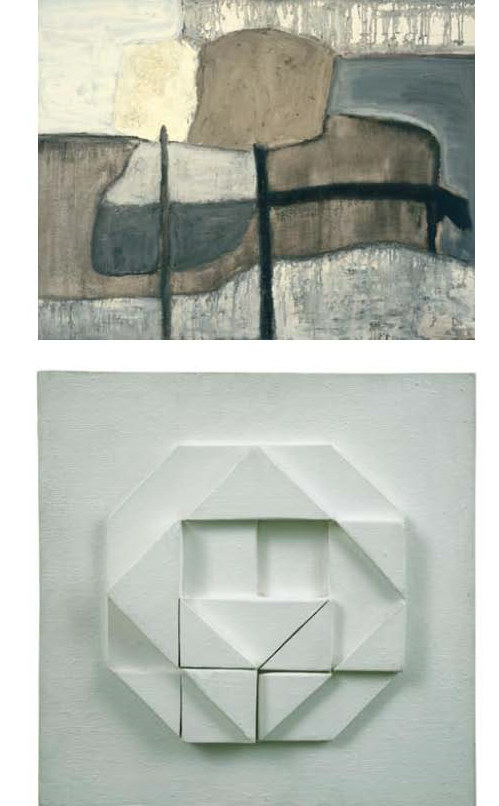

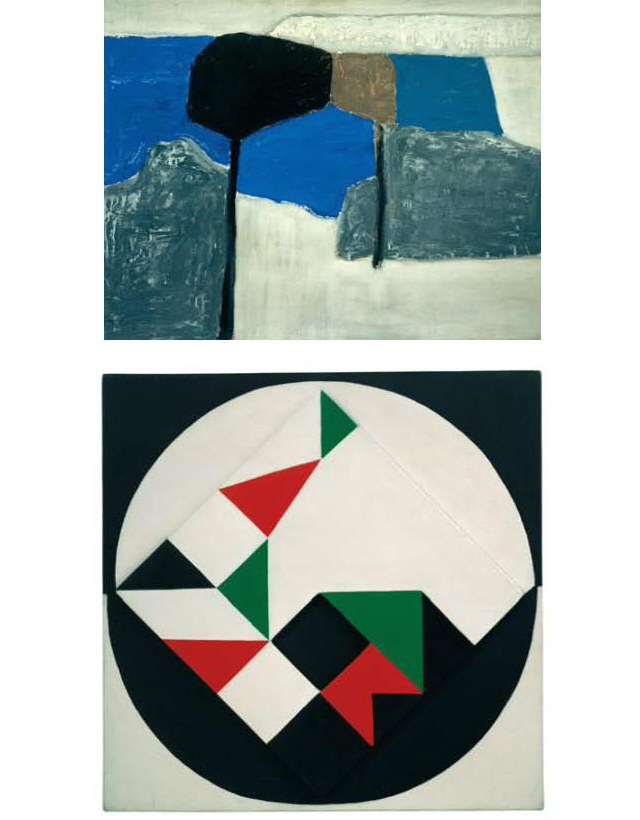

above top: Floating Tree 1958 oil on board 71 x 91cm

Private Collection above: White Relief 1970 painted wood mounted on

hardboard 37.7 x 37.7cm

above: Dying Poppies 1987 pastel and chalk on grey envelope 24 x 22.5cm

Purple Anenomies in Sky Blue 1988 pastel and chalk on coloured envelope

36 x 25.5cm

above top: Trees on the Shore 1958 oil on essex board 71 x 92cm Private

Collection above: Half in Half c.1970/71 painted wood mounted on

hardboard 58.4 x 58.4cm

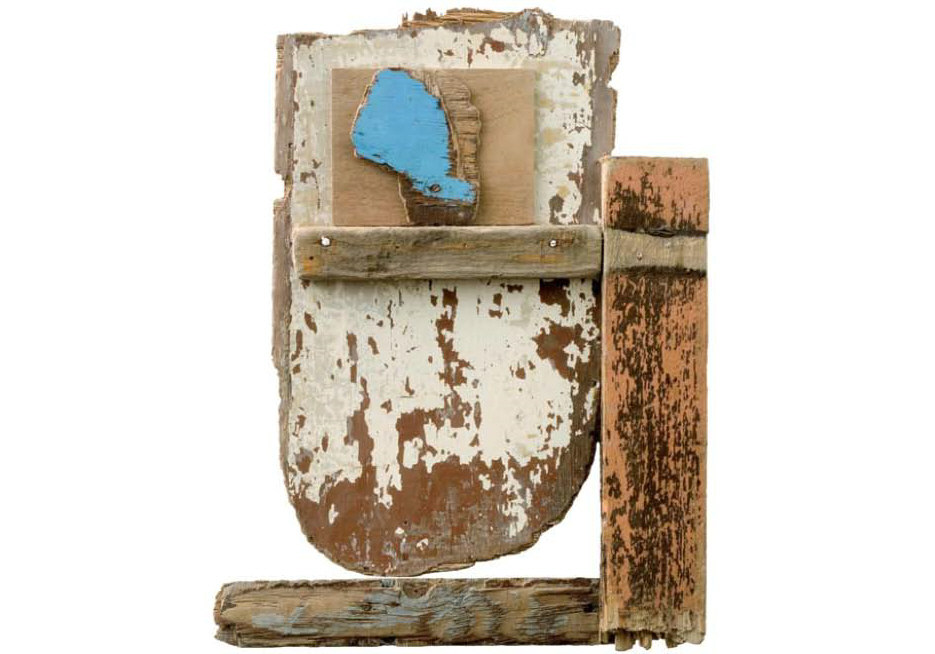

Detail of studio

For some time Mellis had been in the habit of gleaning firewood during

walks along the shore or in the country (she had been living in Suffolk

since 1950). Once she began to think of the domestic woodpile not as

free fuel but as a treasury of unique objets trouvés, however, it became

impossible simply to burn it. The stack in the studio grew. In 1979 two

more driftwood reliefs came out of it; in 1980 ‘a great spate of them’.

3 The series continued for more than twenty years. Judging by their

titles, Mellis sometimes thought of her constructions as purely abstract

formations of shape and vivid colour (Rust and Yellow, 1990), sometimes

as figures or scenes that inexplicably ‘emerged’ from her intuitive

process (Evening Walk, 1986), and occasionally as semi-representational

icons (3 Saints, 1987–89) that she fashioned with the involuntary

artifice of a sleepwalking toymaker.

Three Saints 1987/99 driftwood construction 48.5

x 42.3 x 4.5cm

Margaret Mellis aged 16, 1930 Margaret Mellis c.1932

Surrealism is almost a century old, but we still often read found

objects in a surrealistic spirit, as though they gave physical form to

the workings of our own minds. The sudden collision of chance and

recognition is so satisfying because, in good surrealistic style, it

feels like a link snapping into place as the unconscious greets itself

in the external world. Where did Margaret Mellis, daughter of a

Presbyterian missionary and student of serious, respectable Scottish

fauves, learn to respond in this way? It could well have been in Paris,

where she must have known something of what Breton, Picasso, Ernst,

Duchamp and Man Ray, among others, were up to in the 1930s. Or even

through the imprint of Stokes’s forceful personality. Although, as an

authority on Italian Renaissance art, he felt little enthusiasm for such

anarchic modern phenomena as Dada or Surrealism, this was more than

compensated for by his body-and-soul immersion in psychoanalytic theory.

Wherever her instinct for passive intentionality in art, for the artist

as simultaneous maker and medium, came from, she could hardly have

Marine City driftwood construction 64.8 x 64.8 x

7cm

expressed it more clearly in a description she wrote in March 1990 of

the genesis of her construction Bogman (1990):

‘I found a boat skeleton in the marsh. It was half underwater, but

not rotted. The dark blue paint was cracked & curling off it … I laid it

down on the studio floor … almost without touching them bits of wood

came out of my wood pile & lay down on the broken bones, leaving little

gaps & splits of different shapes & sizes.’5

After several months, during which, while she worked on the piece for

two or three hours every day, it also ‘got kicked out of shape at least

twenty times’, the moment came when, ‘I knew exactly where each bit had

to go. There was no choice … They couldn’t wait another minute.’ This

final session lasted five and a half hours; then, as she lifted the

completed construction off the floor to view it properly, ‘I got quite a

surprise to see that I had a kind of man there. Later, I realised he was

a Bog Man’. She did not know when she started that this strange figure

would materialise, with his broken bones, his look of having been

‘impaled on a plank

Bogman Jan-March 1990 driftwood construction 176.5 x

49 x 5.5cm

which had become part of his body’. Five years later, Mellis was still

describing the creation of her constructions in similar terms: ‘I work

as if I were making an abstract construction’, but then, ‘Something

begins to happen by itself … When I start putting pieces of wood

together, I am aware only of how the shapes and colour relate. I have no

idea of what may happen on the way, or at the end.’ 6 In almost all

Mellis’s statements about her constructions, they are said to have

‘emerged’ – unplanned, unprepared-for.

Although Mellis discovered that her driftwood constructions delivered

their final ‘surprise’ through a process very close to Surrealist

automatism, I don’t want to make too much of their kinship to such works

as Hans Arp’s painted wooden relief The Entombment of Birds and

Butterflies (1916–17) or the assemblages to which Kurt Schwitters gave

the name Merz, or even, in their flayed surfaces, to the paint effects

achieved by Max Ernst’s technique of decalcomania. By the early 1970s

she was certainly aware of Schwitters’s work, which she saw in London

around that time in Philip Granville’s collection at Lord’s Gallery. Her

habits of hoarding all sorts of

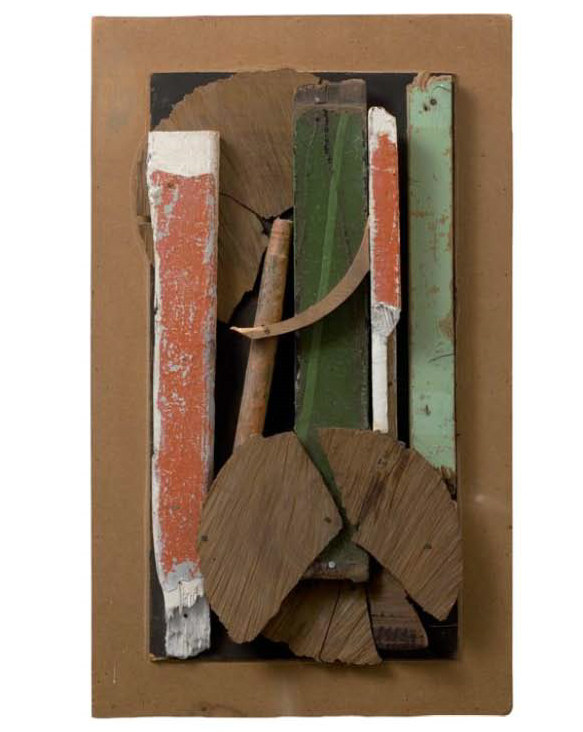

Nine 1980 driftwood construction 39.4 x 43.2cm

Ten 1980

driftwood construction 76.5 x 45.7cm

Thirty Six

1983 driftwood construction 64 x 55 x 7cm

chance finds, of garnering even kitchen waste as potential material for

art, were, however, already well-formed; as an inspired magpie,

Schwitters struck her less as a revelation than as a man after her own

heart. And in terms of colour, in any case, she liked things much

stronger than most of the pioneers of collage and assemblage: Picasso,

Braque, Arp, Schwitters – their excisions from the workaday world

generally stuck to the café tones of scrubbed wood floors, varnished

tabletops, smoky wallpaper, thumbed newsprint. Running deeper, in fact,

than any such influence in the use of found objects or assemblage, was

Mellis’s instinct for, and pleasure in, a certain approach to creating

visual arrangements and orchestrations of colour that was current in

1930s’ Paris but which never quite took root in British art.

Early on, the nature of her personal and artistic relationships to other

members of the 1930s London avant-garde revealed her individuality. No

sooner had Margaret and Adrian moved in April 1939 to Little Parc Owles,

a large house overlooking the sea near St Ives, than a steady stream of

house guests began to turn up – sculptors, painters, writers – a

roll-call

Nineteen 1980 driftwood construction 35 x 68.6cm

Margaret Mellis, Telfer (on right) with Miriam and Nina Gabo

Britain’s modern cultural elite, among whom Stokes was one of the

best-connected men of his day. In August, shortly before war was

declared, Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth and their young triplets

arrived (then stayed for three months), to be followed by the refugee

Russian Constructivist sculptor Naum Gabo and his wife Miriam, who

rented a seaside bungalow near by. Margaret, who was much younger than

Adrian and most of his artist associates, may have taken a ringside seat

as they continued their high-octane Hampstead conversations into the

Cornish autumn, but Nicholson – habitually generous, at least where

junior artists were concerned – encouraged her to get on with some art

of her own. The unremittingly persuasive Gabo, meanwhile, was already

cutting, bending and pasting little maquettes that embodied his ideas of

‘dynamic’ space, modest cardboard tokens of the inevitable dawning of a

world-encompassing Constructivist future. Mellis’s first collage,

elegant and restrained as a Nicholson still-life, coolly geometric as a

Gabo construction, nevertheless reveals the sensibility that set her

apart from the rest of the Little Parc Owles crowd.

FRAIS 1995 driftwood construction 41 x 58 x 7cm

3rd Collage July 1940 mixed media on card 26 x 33cm Private Collection

Humour, or at least a pervasive ‘charm and lightness’, is part of it.

Dated July 1940, 1st Collage contains a small,

upended white rectangle on which the word VALUE is printed in capital

letters. Whether or not she deliberately intended it this way, the idea

of value as a pasted-on snippet offers both welcome relief from, and a

challenging antidote to, the earnest atmosphere in which discussion of

art took place chez Stokes. From the same month, Mellis’s 3rd Collage

contains a fragment of crossword puzzle; the blank squares within the

square suggest, perhaps, that anyone wanting to determine the meaning of

this piece will have both to seek the clues and to find the answers

themselves. There’s an element of play – of teasing, even – in her

choice of mind-game material, since its reason for being where it is in

the collage lies not in its intellectual content but in its ‘intuitive

placement’ 8 in relation to an opaque black rectangle containing a

scissored white disc, a minute white triangle and a squarish yellow

rectangle within a circle within a rectangle of grainy brown.

Whip (untitled) driftwood construction 76.2 x 61.2

x 5cm

Alongside charm and lightness, there were other ways in which Mellis’s

little collages announced their independence of the milieu in which they

were made – ways that Stokes might well have found hard to accept. One

of his personal theories was that all art could be categorised as either

carving or modelling. Even painters could be carving artists, if their

work involved bringing some latent reality to the surface, a process of

disclosure rather than accretion. Modelling, by contrast, meant laying

on paint or piling up clay, for example, to construct objects that,

however impressive in themselves, could essentially never be more than

surrogates. Mellis’s collages sailed debonairly through a gap in

Stokes’s thinking: their active principle involved neither carving nor

modelling but was based on arrangement, moving the elements of an image

around until she hit on an unforeseen ‘rightness’. This wasn’t the way

most British artists worked, including Nicholson and Hepworth. While

they hugely admired Mondrian’s simplification and control of the visual

surface, their own respective practices remained grounded in a belief in

the virtues of shaping their materials by hand, religiously

In the

Night 1993 driftwood construction 74 x 90.5 x 7.5cm

rubbing, sanding, scraping, carving, colouring. Hepworth in particular

talked about art as if it were a transcendental form of manual labour.

In Paris, on the other hand, artists of very different persuasions

shared a fixation on the nature of the organised surface. In their early

experiments with collage before the First World War, Picasso and Braque

realised that raw material could be captured directly from the texture

of daily life and redeployed it as art, not through traditional artistic

techniques but as a result of the way it was arranged. For his part,

Matisse moved discrete areas of painted colour around on canvas, pushed

the charcoal lines in his drawings this way and that, in devoted pursuit

of the ‘art of arranging’. 9 From her encounters with modern art in

France, Mellis either learned or found that she already shared a similar

delight in ‘arranging’. Her 1940s’ collages, so often said to be

indebted to Gabo’s Constructivism, were in essence nothing like. Gabo

believed that there were strict limitations to what could be achieved on

a flat surface (he had a running dispute with Mondrian on this point).

He

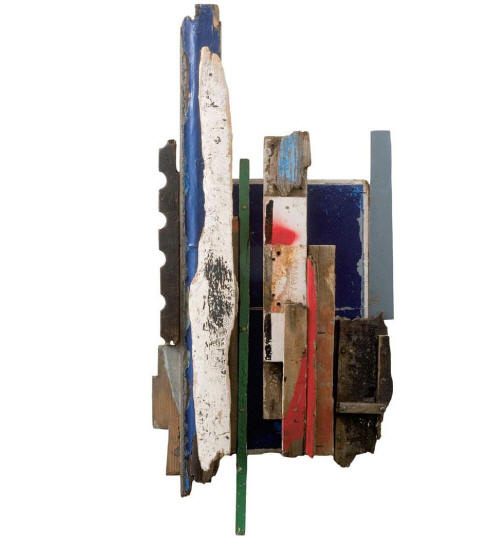

Scarlet Undercurrent Nov 2001 driftwood construction

198.3 x 94 x 10cm

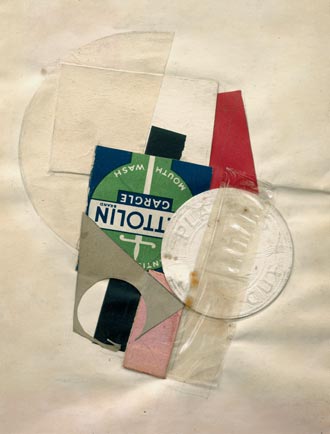

Blue, Green, Red and Pink Collage 1941 mixed media on card 24 x 16cm

Private Collection

had little interest in two-dimensional collage, and would never have

done as Mellis did in using the green and white label from a bottle of

‘Dettolin Gargle’ mouthwash as a circular motif in an otherwise pure

abstract design.

The Dettolin label in Blue, Green, Red and Pink Collage (1941)

represents more than a serendipitously geometric, coloured shape plucked

from obscurity to become abstract art. Redolent of unidealised

domesticity – bathroom cabinets, tooth mugs, shopping lists – it is a

found object that (we can guess) would have slipped beneath either

Stokes’s or Gabo’s intellectual radar but to which Mellis’s gaze was

alert. Nicholson would possibly have enjoyed this touch; but then again,

the ordinary objects in which he took visual delight tended to be more

conventionally either tasteful or toylike – a patterned jug, a striped

fishing-float, a playing card. In the late 1930s Nicholson occasionally

designed adverts, but he kept this side of his work separate

Sinking

Boat 1989 driftwood construction 61 x 43 x 3cm

Cucu (reworked) 2001 driftwood construction 38 x 41 x 10cm

from his serious abstract paintings and reliefs. Ensconced as she was

within Britain’s modernist inner circle, but also trying to run a home,

Mellis saw no reason why household product design and pure abstract art

shouldn’t share the same sheet of paper. The impulse that later led her

to make constructions out of miscellaneous lumps of driftwood was the

same that spurred her to introduce a mouthwash label, a square of brown

parcel paper or the badge from Sobranie cigarette box into her collages.

Far more than the influence of Nicholson or Gabo, it is the spirit of

Alfred Wallis that can be felt in both the early and late phases of

Mellis’s work. While modernist intellectuals praised and patronised the

elderly self-taught painter, Mellis seems intuitively to have empathised

with Wallis’s own feelings about his art – how, when he painted on

discarded packing crates, Quaker Oats boxes, any old scrap he could

find, an inner world of Bible stories, memories of seaports and paranoid

fantasies emerged in the guise of full-rigged ships, spectral fish or

startled house-fronts whose totemic strangeness belied the epithet

‘childlike’. In a phrase that

Toy Cupboard (Thirty) 1983 driftwood construction

54.6 x 59 x 14.6cm

could apply to Wallis himself, Mellis’s long-time friend and supporter

Douglas Hall described her ‘alchemist’s ability to transmute base

material into fine art’. He detected a further, moral, dimension to her

constructions (in its way as foreign to modernist ideals as Wallis’s

atavistic Puritanism), which he identified as a ‘passion to save and

raise up the rejected’.10 Whether or not her art has a redemptive motive

of this kind, it is an art in which the strictest canons of

modernist-abstract taste manage to coexist with an equally forthright

but utterly un-modernist negation of hierarchy. This paradox is one of

the features that, confronting the fantastic jumble sale of objets

trouvés, art brut, assemblages and installation pieces with which the

pages of late twentieth-century art history are heaped, clears a space

for Mellis’s constructions that is entirely their own.

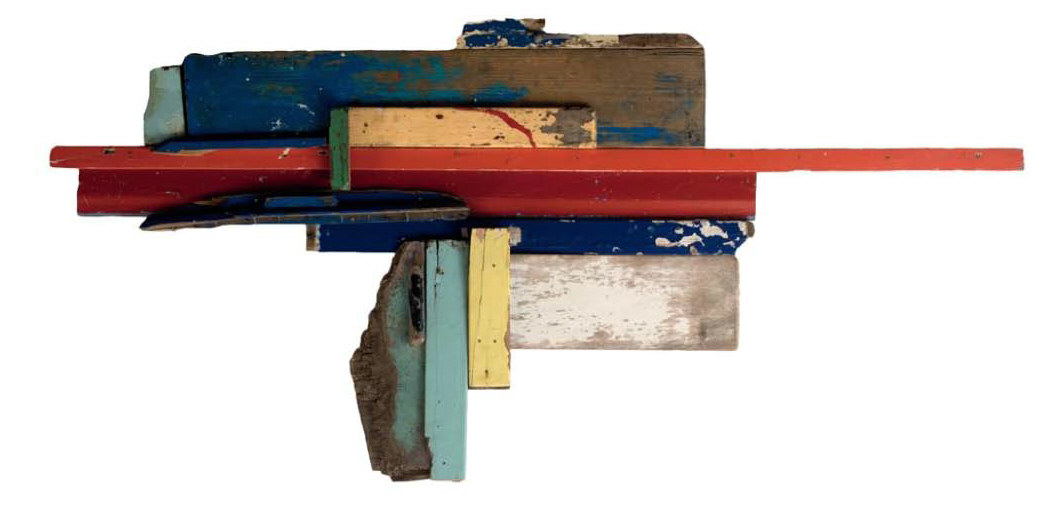

Another feature is her distinctive response to found material, which

seizes not so much to the objecthood of chance finds as on found colour.

Rust and Yellow (1990), for example, could be imagined reprised in

muted, salt-scrubbed tones; it would still be a substantial piece, but

it

Rust &

Yellow 1990 driftwood construction 89 x 110 x 10.8cm

would lose most of its point. The movement in the top left-hand section,

from bare wood to brown paint to yellow then red draws intensity from

the colours’ interaction in a way that recalls Mellis’s ardent

admiration for Matisse. It aligns her with the most Francophile of the

postwar St Ives generation: Heron, whom she thought perhaps too

fastidious, and Hilton, whose fierce mediation between license and

simplicity got results that appealed to her. In Bottom of the Deep Blue

Sea (1996/97), while the sections of blue-, white- and green-painted

marine plywood are again configured like a abstract painting – in their

blowtorch jaggedness closer to Clyfford Still, perhaps, than Heron or

Hilton – much of the colour’s vitality derives from the fact that it is

not laid on deliberately but instead orchestrates the effects of chance.

If, as Bonnard insisted, an artist’s real worth lies in the quality of

their looking rather than their skill with a brush, by leaving paints

and brushes to one side and using found colour, Mellis asks us not to

admire what she has made but to see what she’s seen.

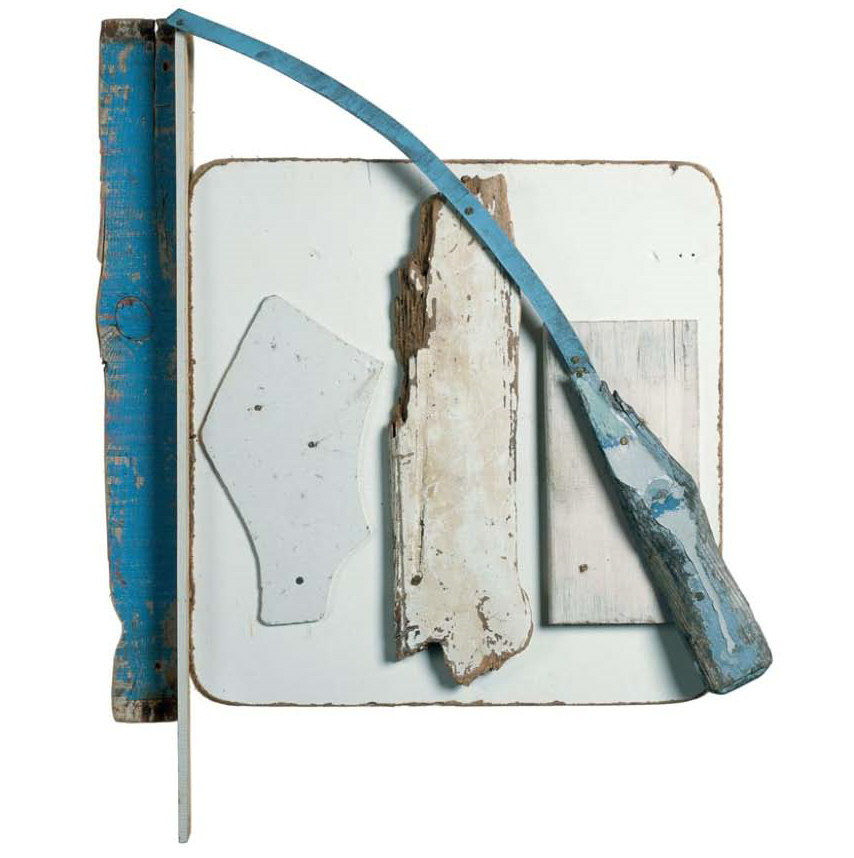

Bottom

of the Deep Blue Sea 1996/97 driftwood construction 88.4 x 106 x 6cm

The torn-looking patches in Bottom of the Deep Blue Sea or ‘F’ (1997) or

Through the Window (1990), where the wood grain beneath the paint is

exposed, echo the look of ripped posters on a wall, reminding us that

these surfaces consist not only of forms and colours but also of

physical depth and texture. We sense, too, the action of time. The work

of art has its history, but its constituent parts have histories of

their own – they have already been something else (or several things – a

tree, a boat, a wreck). Put together by Mellis, usually with no, or

minimal, further intervention, they have not entirely shed their former

lives. Here some part that had once been nailed or glued to a board has

dropped off, leaving its grainy shadow; here are the tiny stigmata left

by screws, nails, drill holes. If I had to explain why I find it harder

to take my eyes from these scarred, peeling remnants than from intact,

highly finished surfaces, I would hazard that it has to do with a kind

of

Through the

Window 1990 driftwood construction 57 x 44 x 3cm

illogical narrative expectancy – if bits of driftwood, as Mellis seems

to have felt, could tell her where they belonged in a construction,

surely they can (if we stare for long enough) reveal their meaning. Or

is it that Mellis’s layering of surfaces and signs feels almost

photographically compelling, as when a camera picks up texture in such

detail that it ghosts the effect of touch? After the finding, searching

and emerging had all taken place, she referred to her finished

constructions as a ‘transformed total’. I would change the tense here to

a present participle, since, even as you look at these works, the

transforming seems still to be underway. It is as if, though all the

pieces have fallen into place, the hands of the clock have not stopped.

January 2008

Rising Deep 2001 driftwood construction 116 x 55 x

10cm

Margaret with her son Telfer and grandson Laurie, Walberswick Ferry

c.1987

NOTES

1 The full title was Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques

Appliqués

à la Vie Moderne.

2 As reported by Douglas Hall in a talk given at the Aldeburgh Festival

in

June 1991 (‘Margaret Mellis: Abstraction, Creation and Intuition’,

unpublished typescript, pp.10–11).

3 Margaret Mellis, ‘Driftwood Reliefs’, unpublished typescript, dated 13

January 1990.

4 Douglas Hall has described the humanoid paddle shape that appears in

some of these constructions as ‘an apt symbol for the soul’, a ‘perfect

little

icon of contemplation and hope’ (1991, p.13).

5 Margaret Mellis, ‘Bog Man’, handwritten statement dated 14 March 1990.

6 Margaret Mellis, statement dated April 1995.

7 The phrase is Mel Gooding’s (‘A Love of What Is Real: The Art of

Margaret

Mellis’, introduction to Margaret Mellis: A Retrospective, exh. cat.,

City Art

Centre, Edinburgh; Kapil Jariwali, London, 1997; The Pier Gallery,

Stromness, 1998, n.p.).

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Hall, 1991, p.2.

Article appears courtesy of

Austin/Desmond Fine Art www.austindesmond.com

Essay by Michael Bird was written to coincide with an exhibition curated by Catriona Colledge

and David Archer in January 2008. Photography by Colin Mills.

Michael Bird is author of

'The St Ives artists: biography of Place and Time' and 'Sandra Blow'

both available through the artcornwall shopfront:

See interviews page for

video clips from Margaret Mellis: A life in Colour

|