|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Andrew Lanyon Goldfish Fine Art December 2007

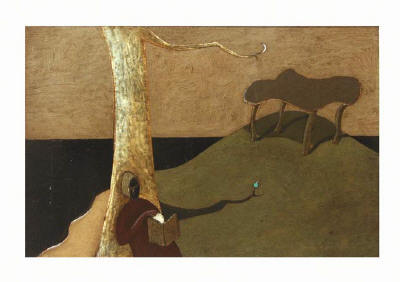

Andrew Lanyon is a unique artist for lots of reasons. Since the eighties he has been one of only a few Cornish artists working in film, writing and photography as well as painting, and he has worked in a way that - in a local context - is defiantly different: that is, in a way that is diametrically opposed to the St Ives school of abstract painting. Perhaps the relationship with narrative is not surprising. Artist's books have been a constant feature of Lanyon's output. In addition he trained as a film-maker in the late sixties, and his work has things in common with that of other artist film-makers like Jean Cocteau and Derek Jarman, with his drawings and paintings looking like storyboards and his sculptures props from a film or stage-show. The exhibition at Goldfish was installed in a way that emphasised these theatrical qualities: dark chocolate brown drapes downstairs created a labyrinth of little grotto-like spaces in which the work was placed. This 'staging' helped create a sense of otherworldliness that fitted the work well.

Much of the work in the show had a similar poetic quality, often nudged along by an evocative title. 'Time's Breath' was the perfect name for an otherwise unassuming sculpture comprising an old clock filled with dandelion seeds. Often made using antiques and discarded objets d'art, there was very little of the contemporary world in the sculptures. Several pieces engaged with history instead: often doing so in a way that was irreverent and playful by finding the absurd in what might have been serious content. An example would be the painting 'Newton' in which a figure in the foreground - who we take to be the 17th Century mathematician - appears to miss the small acid green apple falling to the ground behind him (above right).

This applied to a number of the works for which there was little in the way of explanation, and with so much visual information to digest it was difficult to know where to begin. This overwhelming quality was no doubt intended by Lanyon who, through a sustained and mischievious assault on reason, creates a similar disorientation of the senses in his books. His films, however, are more accessible and direct, and occupy the same universe, but one that seems more familiar and closer to home. As with the paintings, the works that were shorter, less jokey and less obviously caricatured were the most powerful - at least when considered purely as visual art. A good example in this respect was 'The Flower Arranger'. Only two and a bit minutes long, it depicts a woman arranging flowers, each finger of each hand tied by string to a pole; her movements controlled by a small army of puppeteers. All the participants were Lanyon's friends, wearing wellies and fleeces, and looking very ordinary and normal. Slightly slower than real time, and zooming in and out, it is a haunting and dramatic film that effortlessly mixes elements of dream and reality in a way that is completely beguiling. In fact Lanyon's films represent an extraordinary artistic achievement and they deserve to be seen by more people. His work as a whole is not always easy however, and at times it is so full of personal references, caricature and whimsy to be as impenetrable as Cornish gorse. The surfeit of meaning that it contains was amply demonstrated in the Goldfish show, and it is both a strength and weakness. Its complexity is in contrast to much contemporary art, which is made to function as quick-hit photogenic soundbytes: ready-made for our increasingly instant, decentred (globalised) culture. Lanyon's work at Goldfish was infinitely slower and more deliberate and multilayered. And his exhibition, which required viewers to completely switch modes and slow down, belonged to a completely different time and place. RW 22/12/07

|

|

|