|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

Ithell Colquhoun’s Magic of the Living EarthAmy Hale

Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) is remembered as a Surrealist and magician, but these descriptors do little justice to the breadth and depth of her artistic and spiritual practice. She was likely one of the most dedicated and engaged female occultists of the 20th century and her command of Western Esotericism infuses the entire body of her creative work. Over the course of her life, she was involved with a variety of occult orders, including the O.T.O., Martinism, Co-Masonry, Druidry, and Golden Dawn-inspired orders, to name a few. She was astonishingly prolific, having created well over 5000 paintings and drawings in her lifetime. She also crafted scores of poems, short stories, essays, novels, and travelogues, many of which were never published. She had an astonishing command of what she would have perceived as the Western Magical Tradition, with the Golden Dawn system being perhaps her deepest guiding force. In her work we see a fusion of Kabbalah, alchemy, Golden Dawn color theory, nascent earth mysteries and “Celtic” mysticism. It is difficult to imagine how Colquhoun saw the world, experiencing every object as a web of deep correspondences, forces, and entities; a type of vision one can only cultivate after years of practice, study and embodiment.Although Colquhoun was a keen Hermeticist, she was also an animist who saw the earth as alive and possessing spirit and force. Stones spoke to her; trees and caves were evidence of the Goddess showing her most raw and intimate self for those who would see. For Colquhoun, the earth pulsed with electromagnetic currents sourced from underground fountains of energy. Antiquities were the beacons of these sites, marking their power. Colquhoun believed that the ancient peoples who created temples of stone, and the early Christians who followed, had the ability to tap into this energy, to focus it, and to shape a repository for people to come and feel fulfilled by their connection to The Source. Throughout Colquhoun’s writing and sometimes her painting, we see her return to shrines and spaces that marked the human ability to commune with sites of power, telling a story about a spirit-filled earth.Colquhoun’s animism is key to understanding her complex world view, although she joined many magical orders, skirted around the edges of esoteric Christianity and always championed recognition of the Divine Feminine as a way to bring the world back into alignment. At heart, she was motivated by the theory that every aspect of the planet was alive with divine energy and, importantly, that people could communicate with the landscape through practices that would allow them to cultivate their sensitivity. Colquhoun’s worldview involved not only a living landscape but also layers and dimensions of reality populated by forces, spirits, and energies. This worldview is the thread that unites all of Colquhoun’s writing and art about the natural world.Dreaming, trance work, and divination were all methods Colquhoun would use to help attune herself to the natural world and dimensions beyond. She resonated deeply with the automatic processes of Surrealism because they relied upon practices that forced a conversation with other parts of the subconscious and with other realms. Colquhoun also believed that Celtic peoples in particular had special extrasensory gifts and were naturally more in tune with the landscape, and she assumed a Celtic identity to support her own perceptions of natural psychic sensitivity. Although this belief is a deeply problematic position[1] to hold about a group of people, her beliefs about the spiritual receptivity of the Celts reinforced her long-term relationship with Celtic places and spaces. She lived in Cornwall for over forty years, having been compelled by its Celtic history and culture and also the preponderance of megalithic monuments and sacred sites there.

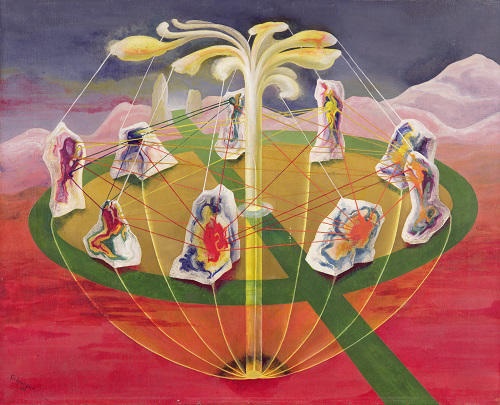

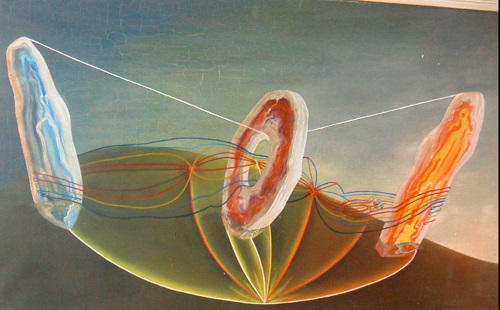

It is evident from Colquhoun’s earliest forays into Surrealism that she wished to convey the earth as sensual, vibrant and as holding secrets. From her earliest paintings and sketches through to her final years, she had a love of painting and drawing the natural world, and she particularly focused on close studies of flowers. In the mid-1930s, as Colquhoun was beginning her explorations into Surrealism, her botanical studies become more and more sexualized, with flowers and tree trunks morphing into lush vulvas and visual metaphors for penetration or sometimes impotence. Her pictures of flowers at this stage were detailed, and while not yet explicit, they were nevertheless intimate and sensual. She chose to paint and draw plants that were already rich with the possibility of double entendre: lilies, gloxinia, bananas and cacti, their true symbolic nature eager to be revealed. It would ultimately be her passion for the natural world and all its mysteries that provided her initial vehicle for the expressions of the mythic, the deeply sexual, and the surreal. Colquhoun’s botanically-based works are the representations of a vital landscape with which we can and should enter into conversation. Flowers and trees are not merely symbolic of sexual principles; they embody them, and they are emblematic of divinity and the sacred power of creation and possibly redemption.As Colquhoun became more involved with Surrealism, her depictions of the natural world became more explicit. She progressively represented bolder sexual depictions of both the male and female form as seen through the lens of vegetation such as Double Coconut (1936) and Pitcher Plant (c. 1936) which is a thinly veiled portrayal of penetration. In 1938, she produced a positively tumescent Aloe. By 1940, her eroticized nature forms engaged with a mythic, archetypal significance, representing the hopeful vitality of the earth and its redemptive potential in the shadow of war. The Pine Family (1940 - above) is a stark lesson about the decaying state of humanity during the crisis of World War Two. The Pine Family depicts driftwood on a beach representing a castrated male, female and hermaphrodite where all genitalia have been disfigured. The male figure is labeled “Atthis”, the female is “celle ce boite” or “the one who limps”, and the third figure is labeled “the circumcised hermaphrodite”. While this painting had internal references within the culture of Surrealism, The Pine Family explores similar themes as Elliot’s The Wasteland, representing Colquhoun’s exploration of the Frazerian myth of the fallen, castrated and resurrected fertility god also recalling the Fisher King with his wounded “thigh”[2].Antiquities as PortalsI am glad not to be an archaeologist, for my lack of status allows me simply to enjoy myself among antiquities. I can interpret them according to my own morphological intuitions without reference to any current orthodoxies or deference to any school of thought—even without strict regard to evidence[3].Ancient monuments were, for Colquhoun, evidence of the genius of early humans, and a reminder of all that humans have forgotten about living in harmony with the land and harnessing its powers. The Neolithic/Bronze Age stone monuments dotting the landscape of Cornwall have inspired the antiquarian and esoteric imagination in Britain since at least the 17th century, when early antiquarians linked them to the Druids, hypothesizing that these were the ritual or astronomical sites of the ancient Britons. Everyone from archaeologists to spiritual pilgrims have tried to penetrate the mysteries of these sites, to recover their original function, and tap into their ancient technologies. Cornwall has one of the densest concentrations of megalithic monuments in Western Europe, which has only added to the mystical allure of the area and reinforced the belief that there is something ancient and powerful lurking just below the earth.While we know today that these stone sites were not artifacts of a Celtic civilization, the idea that the Celts were the inheritors of an ancient mystery tradition of the West, very likely transmitted to them by the mythical super human inhabitants of the sunken land of Atlantis, has remained a perennial facet of the lore of Western Esotericism. It is likely that the concentration of megalithic monuments, holy wells, and remnants of medieval sacred sites that Colquhoun would have encountered in her early visits to West Cornwall inspired her interests in sacred landscapes and even what would later be known as “earth mysteries”. Colquhoun’s writings from the 1950s on sacred sites in Ireland and Cornwall, brought together a number of cultural and alternative spiritual influences of the early and mid-20th century. These included an increase in interest in pilgrimages to sacred sites in Britain, ley lines, and ideas about electromagnetic currents under the earth’s surface. Although these theories merged in British subculture with the earth mysteries movement in the 1960s, Colquhoun was exploring ideas regarding ancient monuments functioning as interdimensional portals as early as the 1940s.Although Colquhoun was likely inspired by Dion Fortune’s writing about sacred sites in the 1930s, in many ways, Colquhoun’s interest in sacred sites and their power was well ahead of her time. She was synthesizing a number of beliefs and fringe intellectual currents in Britain and other parts of Europe regarding the nature and origins of not only megalithic monuments, but all sacred sites, including ancient churches and stone crosses. It was in this milieu of ideas in the early 1940s, combined with her interests in other dimensions, that Colquhoun developed her theories about stone circles. In many ways, Colquhoun prefigured esoteric ideas about megalithic monuments that didn’t become widespread for approximately twenty-five years. Ley lines did not take on supernatural associations until the publication of John Michell’s The View Over Atlantis in 1969, though the idea of an ancient network of tracks connecting sacred sites had captivated British antiquarians since the 1921 publication of Alfred Watkins’ The Old Straight Track. However, Colquhoun’s work is consistent with the early twentieth century stirrings of what today is frequently referred to as “alternative archaeology”, where the past function of sites is speculated via unconventional or intuitive means. Fredrick Bligh Bond’s use of gematria and psychic readings at Glastonbury Abbey in 1917 were early examples with which Colquhoun would have been familiar.Colquhoun produced many studies of Cornish stones over the central decades of her life. Around 1940, Colquhoun completed some very early and quite rough watercolor sketches of Cornish monuments, the Men an Tol and Lanyon Quoit, although she displayed no further evidence of the complexity of her thought around these monuments. Within a couple of years, however, Colquhoun developed some unique full studies of the Nine Maidens/Merry Maidens and the Men an Tol that suggest the merging of a variety of complex esoteric theories about the nature and role of the monuments ranging from wells of energy coming from the earth to, potentially, her research into other dimensions. These paintings are unique and complex and we see nothing else like them in the rest of her oeuvre.In 1941/42, Colquhoun completed two outstanding paintings of Neolithic or Bronze Age monuments, The Dance of the Nine Opals (1941 - below left) and The Sunset Birth (c. 1942 - below right), which display the most sophisticated articulation of Colquhoun’s theories around sacred sites and which merit slightly more discussion than some of her other sacred landscape works. These complex paintings include a number of ideas and theories that Colquhoun was working on quite feverishly, yet they never seemed to blossom into a major body of work. In the early 1940s, Colquhoun was concentrating theoretically and artistically on energy flows and portals, and these take shape in a number of her artistic projects at the time, including these particular works on Cornish stone monuments. Her lifelong obsession with the fourth dimension and tesseracts is also reflected in the sketches of Dance of the Nine Opals. In these luminous and visually complicated paintings, she explores a wealth of ideas around the megalithic monuments as energy conduits at points in the earth that can act upon the energy centers present in the human body. These theories intersected with her wider esoteric thinking at the time, and they are early articulations of what she would refer to as “the living stones”. Colquhoun’s usage of this phrase may have had its source in Ouspensky’s Tertium Organium, which itself may have been inspired by Peter 2:5 : “Ye also, as lively stones, are built up a spiritual house, an holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices, acceptable to God by Jesus Christ.”

|

Early

Botanical Period and Surrealism

Early

Botanical Period and Surrealism Dance

of the Nine Opa

Dance

of the Nine Opa The

stones in

The

stones in