|

Curation as

Unstable Monument

Amy Shannon Halliday

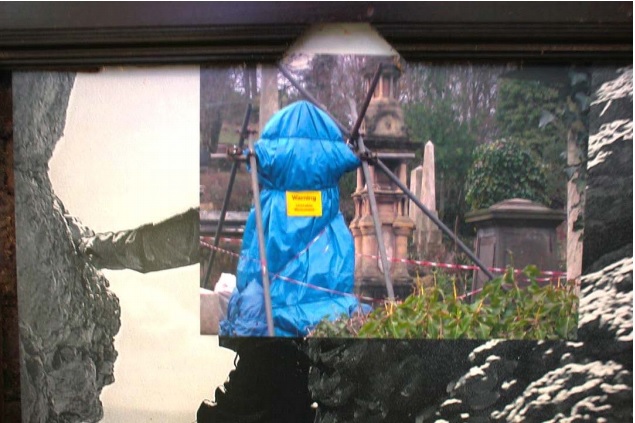

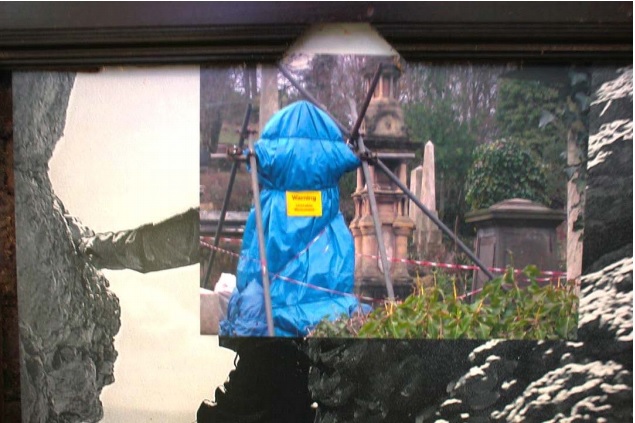

Making his way carefully through Bristol’s Arnos Grove cemetery early in

2015 after ankle ligament replacement surgery left him on crutches,

artist Matthew Benington found himself drawn to a precarious grave

marker wrapped in a blue tarp, covered in hazard tape, and surrounded by

scaffolding: “Unstable monument,” it announced. For Benington — who uses

found and inherited materials, assembled fragments, and large-scale

printmaking processes to grapple with questions of history, memory,

identity, and forced displacement (including that of his grandmother

from eastern Germany in the 1940s) — the sign offered a powerful

rejoinder to the rhetoric of fixity, coherence, and stability embedded

in traditional public monuments, institutions, and even notions of the

self.

“Warning: Unstable Monument”, snapshot from Arnos

Grove cemetery inset into an installation by Matthew Benington.

Over time, Unstable Monuments became a framework for thinking

about art-making, self-making, and history-making as fundamentally

contingent, interrelational (and intergenerational) and unfinished.

Working closely with fellow artist Jesse Leroy Smith, Benington has

developed this line of inquiry into a state of curatorial emergence.

Rather than participating in the pristine "white cube” gallery sector,

Smith and Benington have worked with community partners to create a

series of ambitious artist-led projects set in spaces of transition or

precarity: an old warehouse in the ex-industrial mining town of Truro,

Cornwall; a derelict complex of nineteenth-century magistrates courts

and jail cells in Bristol’s Bridewell Street. As artist-curators, the

two are interested in anti-monumental materials and fugitive forms, and

in creating the conditions by which emerging and established artists

might experiment and collaborate, responding to specific sites, and to

each other. The resulting exhibitions unfold dynamically: more than a

little “out of [their] hands” laugh Benington and Smith over a

conversation about their recent Bristol-based project.

The port city of Bristol — where a statue of merchant and slave trader

Edward Colston (1636-1721) was erected in 1895, and famously toppled and

tossed into the river by anti-racism protestors in June of 2020 — is

freighted with the legacies of the past. Like the Colston statue, the

former Magistrates Courts are Grade II listed on the National Historic

Register. The courts have languished, largely empty, since the 1970s,

variously used as a squat, a pop-up rave venue, a laser quest labyrinth.

After years of advocacy, partnership and business-case building, the

courts are set to be transformed into a creative entrepreneurship and

up-skilling hub for marginalized youth. Renovation and restoration are

due to begin in late 2022, but in March and April, Benington and Smith

worked with Creative Youth Network (CYN), the charity spearheading the

transformation, to run artists’ residencies in the space, culminating in

a one-weekend-only exhibition that reverberated well beyond its walls.

Katie Henning, Displace, 2021, public art performance,

Richard Mark Rawlins, Public Intervention. 2020

Approaching the buildings for the exhibition, the first work to catch my

eye was a live performance and ephemeral public artwork by Katie

Hanning. Using hand-made stencils filled in with soil gathered from

significant sites around Bristol, in Displace, Hanning inscribed

the concrete courtyard with words bearing witness to her experience and

encounters with people and places during the process of collecting and

“moving” the earth. Hanning is interested in the invisible barriers that

prevent audiences from engaging with art in traditional institutional

settings. Her work, instead, is deeply informed by movement and

conversation; the carrying of ideas and materials across thresholds. The

outlines of the words are scuffed and occluded by the feet of visitors,

spreading the soil in their wake, but their ghostly traces remain:

“yielding” I read. I think I can make out the words “from where we

came…” I stand for a while, and watch. Hanning was part of an

exhibiting/performing group of art students from the University of Bath

Spa, convened and mentored by Bristol-based artist and educator Young-In

Hong. Henning’s placement at the entrance foregrounded the significance

of live performance and durational media in Unstable Monuments,

as well as the curators’ commitment to young and emerging artists

(another call for artists went out through the Creative Youth Network).

At the same time, as Smith emphasises during our conversation,

mentorship is multidirectional, with many artists working closely

together during the residency to respond to the buildings and to

Bristol, and to the ideas, challenges and experimentation that working

together fomented.

Architecturally and affectively, the building is very clearly divided

between ground-level courthouses and offices (large, airy, full of

natural light) and a series of subterranean cells (small, damp, dark).

Across both, and in the interstitial spaces of stairs and corridors,

several of the artists’ works directly confront the vexed question of

monuments and public memory with deliberately anti-monumental materials

and processes. Richard Mark Rawlins explores the tension between the

invisibility and hyper-visibility/surveillance of the Black body in

public spaces through a series of Public Interventions (2020)

around London. In each performance, the artist stands, bare torsoed —

outside the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, or with the Winston

Churchill Statue in Parliament Square — and holding in front of his face

a range of texts such as Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I'm no Longer Talking

to White People about Race. Performance documentation is installed

as an unassuming series of black and white poster reproductions,

wheat-pasted to a courtroom wall just above the room’s dark wood

panelling: documentation includes an email in which Rawlins writes to

Bristol mayor Marvin Rees about staging one of his interventions on the

empty Colston plinth (the request was denied).

Rawlins’ interventions face Matthew Benington’s Hide (2015).

Though the structure is reminiscent of a child’s blanket fort, the

softness of the exterior gives way to an interior assemblage of large

sealed etching plates. Painstakingly hand-painted with acid-resistant

varnish directly onto each steel plate, building each tonal layer to

create the image, the surface images are derived from family, found, and

location photographs that are part of Benington’s ongoing research into

forced displacement. Focusing primarily on the kinds of vernacular

imagery that families forced to flee carry with them, rather than the

direct representation of conflict or flight, the installation is a

powerful invocation of the lived reality — the fullness, depth,

entanglements, and exquisite detail rendered as etched traces — of each

life impacted by extreme sociopolitical upheaval.

Matthew Benington, Hide, 2011-2018

Marianne Keating’s Landlessness, a dual screen video installation

in a nearby courtroom, is similarly poetic-yet-incisive in its

exploration of migration and diaspora: in this case the recruitment and

transportation of Irish indentured laborers to the plantations of

Jamaica’s north coast between 1835 and 1842. Keating overlays video

footage of localised land- and seascapes (which might otherwise read as

picturesque) with textual traces: fragments of testimony and records

recovered from the National Archives in Ireland, England and Jamaica are

assembled as if in conversation, tracing past and present connections

between Ireland and the Caribbean, routed through British colonialism.

An archival sensibility and attentiveness to materialising,

interrogating, and layering “traces” – the remaining signs, partial and

contingent visual and textual residue of past events – is a strong

undercurrent in Unstable Monuments. Traces link Benington’s

photographic referents (and their transformation, in turn, as etched

marks in Hide, or physical traces of the dark Bristol cells

brought to light through cyanotype processes in The Architecture of

Enclosure 01) to Keating’s videos, Hanning’s scattered earth, and

James Hankey’s quietly profound Dave Was. In the 36-page kettle

stitch book, Hankey transcribes and archives the messages and musings,

profanities and provocations he found on benches and walls, on the

dividing panels between cells, seating areas and toilets during his

residency: an insistence on presence in the face of prison’s rough

poetry of erasure.

Marianne Keating, Landlessness, 2017-2022

Several works in Unstable Monuments were made on site. Laura Robertson’s

massive sculpture, Body Everted, was made from construction

insulation (a fundamentally liminal material) draped, folded, assembled

and augmented around a wooden scaffold in a small cell, its softness and

organic pliability turning the language of the monument inside out. As

work took form in the space, so other artists responded in performance.

Lily Serendipity, for example, wove her wandering way around Body

Everted in her piece, Unmasking, while Antonia Purdie’s

choreography-as-lifeblood seeped from (and back into) the fluid handling

and crimson palette of Jesse Leroy Smith’s Pollinators

installation. Callum McCutcheon, whose practice is a means of exploring

and mediating conscious and subconscious mental states, spent days

translating his affective experience of the cells (anxiety, uncertainty,

alienation, scattered attention) into a multi-media installation that

was utterly mesmerizing. Reverberating sound, sculpture, wall drawing,

and found objects read as a kind of emotional notation or set of jarring

frequencies, the disparate elements engulfed by video projections of

tumultuous waves crashing over, through, and between cells.

Laura Robertson, Body Everted, 2022

Callum McCutcheon installation view, Antonia

Purdie, Unmasking

Local artist Orian had previously been experimenting with carving and

painting wooden skittles but, through his time in residency and in

discussion with other artists, developed this work into a large-scale

installation. Skittles is a historical lawn game and target sport that

has been played for centuries in England in public houses and clubs and

backyards. Taking on this seemingly benign game, and with it ideas of

the “innocence” of childhood, Orian’s skittles are shaped by strong

mental references from his own childhood: comics, popular music, and the

casual racism of Enid Blyton’s children’s books (exported to the

colonies where I, as a white South African, grew up with them too). The

artist takes aim at the powerful hold of early representations and

playground encounters on our racial and social imaginations: the work is

all the more powerful for its positioning in front of a judge’s seat in

a court that may well have been involved in juvenile sentencing.

Orian: ‘Eat,Pray,Clean, Butterfly Effect, ‘Effigy,

Music is the Answer, Hard Target, Skit Skull, Foolish little…,‘Fucking

Exit…,I was Born to Fight, Inside Out, Not For Sale, Skittle Me

Sweet(nfs), An Eye…, Since Power is your God(nfs’. 2021-22

Many works made on site during the residency or installation period were

also unmade during the process of public exhibition. Set in a small,

sun-drenched office between courtrooms, Alison Larkman’s chair

installation, for example, invited visitors to sit, enthroned. Yet each

use strained the fragile vellum seat, stitched from fragments and

stretched taut across the wooden frame, until it gave way. Meanwhile

Ling Ho’s haunting clay figures — their heads formed into loudspeakers

as if an embodiment of protest, assertion, or authority — slowly

dissolved over the course of the weekend, the unfired clay subject to a

constant overhead drip, the water undermining its structural integrity.

Alison Larkman

Fragile Skin and Ling Ho Untitled

Given the imminent renovation of the building, as well as its place on

the National Historic Register, artists were not allowed to make any new

holes or add any new fixtures to the walls, a set of aesthetic and

curatorial constraints that heightened a sensitivity to site. Jesse

Leroy Smith’s response was especially striking, measuring out each niche

and negative space in an entire courtroom’s austere wooden panelling and

filling the magistrate’s box with vibrant images of pollinators – birds,

bees, bats, and flowers – that offer a surge of imaginative possibility

and wonder just barely contained by the edifice’s edges. On the three

walls facing and adjacent to the magistrate’s box, Smith presents an

elegiac series of thirteen large-scale portraits, devised and painted in

situ. Operating simultaneously as a personal pantheon, a jury of peers,

and a freighted Last Supper, Gil Scott Heron, James Baldwin, Diane Arbus,

and Vivianne Maier bear witness alongside Raghbir Singh, the first

non-white bus conductor after Bristol’s 1963 Bus Boycott (one of

Britain’s first black-led campaigns for racial justice), and an unnamed

Romani boy killed during the Holocaust (and whose image at the Berlin

Holocaust Museum seared itself into the artist’s consciousness). The

artist’s son, collaborator Matthew Benington, and Creative Youth Network

artist Lucia Harry, whose insights deeply influenced Smith’s thinking

about the Unstable Monuments project, appear, too, among these cultural

icons, looming equally large in the artist’s mind. Painted in oil on

tracing paper, the large substrate floated and buckled in the damp, and

was translucent in the morning sun: the scrim of peeling walls breathed

through the portraits’ thin surfaces.

Leroy Smith Pollinators

As I left the exhibition, I climbed back up the stairs from the cells

and decided to wander the upper halls one more time – small offices and

hallways seemed to elude and surprise me at each turn. Somehow, I had

missed a room with peeling walls, small pod and seed-like sculptures

laid on unobtrusive shelves, and a square cage set on the floor. It was

filled with what looked to be massive cowrie shells with printed indigo

words: DERIVATIVES. SUB-PRIME. HUMAN CAPITAL. Closer inspection revealed

the works to be ceramic transferware, the blue and white motif

reminiscent of the popular trade in transfer wares in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries. With their lustrous decorative surfaces and

“exotic” associations with hand-painted Chinese porcelain, the mostly

Staffordshire-made ceramics became increasingly popular in the United

States. Often, these ceramics featured scenes of “quintessential”

American landscapes and historical accounts, participating powerfully in

the construction and circulation of the country’s heroic (and

exclusionary) founding narrative. Dan Pyne’s replacement of these

popular images with the resurgent heroes of contemporary capitalism on

shapes associated with early modes of currency and exchange seems to

suggest that money – which so often bears the official imprint of a

nation’s ongoing self-construction (its national heroes or architectural

triumphs) – has always been a form of monument, a monumental form.1)

Pyne’s title, It’s just business, don’t take it personally, could act

equally as epigraph to the standard apologia for the statue of

“merchant” Edward Colston… MORAL HAZARD, reads another ceramic cowrie.

It is in contrast to this sort of systemic, pecuniary context that

Unstable Monuments as a model for artist-led, community-partnered,

extra-institutional curating shines most brightly: the exhibition as

provocation; as process; as promissory note for further elaboration. In

October, following months of uncertainty over the future of the Courts

after the Bristol City Council denied the final £700,000 it had pledged

to the Creative Youth Network for its renovation (potentially

jeopardising the almost £5.5 million in match funding already secured),

renovation began in earnest. Images surfaced yesterday of the demolition

of the east entrance, making room for a new, fully accessible entryway:

a newly unstable edifice, poised for possibility.

1) African-American artist Nari Ward recently made the

remark in an interview on the Art Angle podcast that money is our

“portable monument,” but is based on a particular (exclusionary)

history.

'Unstable Monuments' was in Bristol

between 8.4.22 & 13.4.22

26.3.23 |