|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Bob Law: a

reappraisal

Richard Saltoun and Karsten Schubert At the end of 2009, the first monograph dedicated to the life and work of Bob Law was published, in conjunction with a retrospective at two galleries in central London (see exhibitions). It was the first chance since the artist’s death in 2004 to encounter the work in depth. In an excerpt from the book, Richard Saltoun and Karsten Schubert reappraise a remarkable life’s work.

Today art historians are forever on the lookout for ‘missing links’ – a particular artist, work or development that allows different historical strands to be fitted together. In this Law should take up a particular place, being the only minimalist who came out of an exclusively British tradition yet arrived at work that could stand in an international context. There is now a new generation of curators

who are not familiar with Law’s work. To be forgotten usually carries

the unspoken charge of ‘rightly so’, yet somehow this does not apply

to this particular case. How did Bob Law come to be forgotten? It is

not easy to write in a professional context about the complexities of

an artist’s personality and their relationship to the work, but in the

case of Law it seems essential (even if only in order to get the

charge of being ‘rightfully forgotten’ out of the way). It is not

accidental that the essays in this book by those who knew him have

resorted to the personal and anecdotal. The strength of his

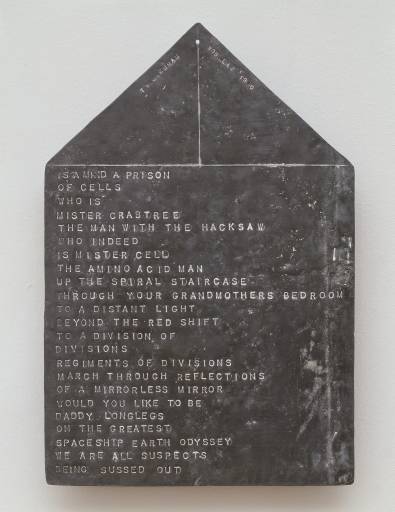

Bob Law’s early biographical records are patchy. He was born in 1934, his father unknown. As a result of the war he had little formal education and left school early, possibly at the age of twelve. He then began a series of apprenticeships and phases of self-tuition. Initially he learned technical draughtsmanship, then geometry; this led him to carpentry and then to architecture. He became highly skilful in all these fields and by the mid-1960s was building and designing houses for a property company run by the collector Alan Power. After two years of National Service in the mid-1950s, he started to paint and draw. He claimed to have been taught art as a child by his grandmother. By 1957 he was in St Ives, meeting Ben Nicholson, Peter Lanyon and other artists. The landscapes of Nicholson may be seen as a starting point for Law’s mature work when considering the way each artist defines the area of the landscape on the paper. During this time, he began to read widely in philosophy, mysticism, alchemy and palaeontology. He had a particular interest in the writings of George Ivanovitch Gurdjieff, Peter D. Ouspensky and Richard Jefferies. Law’s first mature works – the Field drawings and paintings – bring together his interests in Euclidean geometry and metaphysics with his technical skills in draftsmanship and carpentry. As a craftsman Law was highly skilled. He made furniture early on in his career, according to the artist, often as a substitute for sculpture. In 1970 he began to make his own stretchers for his paintings, seeing that process as fundamental to the creation of the whole work. He built sculpture for Donald Judd for his first London exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in 1973. In the early 1980s he turned to carpentry again, fabricating his furniture-sculptures, particularly chairs. Perfect execution and technical competence were integral parts of his creative process.

While Law’s proclivity for erasure can be considered a factor in his current status, there also remained the challenges of the populist response to the art of the 1970s in Britain. Law became the archetypal avant-garde artist to be pilloried. This was evident in the reporting of the Hayward Annual on BBC television in 1977. The presenter, Fyfe Robertson, understood himself as a critic for the people; Law was the subject of a particularly pointed public lambasting. Robertson explained that the exhibition baffled him; he saw in it ‘an undisciplined, despairing, free-for-all meaninglessness’. This sentiment was exemplified by Law’s contributions: The man who seems to me to have travelled furthest down the avant-garde road to nothing and nowhere is Bob Law… What are [the viewers] getting from empty white canvases on a white wall? For me, these things are not art. They’re symptoms of a modern sickness that repudiates standard in almost everything, not just – Bob Law-wise – in art. Robertson later interviewed David Hockney, who made no attempt to grasp the particular nature of Law’s endeavour and commented: Well it seems to me that if you make pictures there should be something there on the canvas. I don’t understand four lines of ballpoint pen round the edge of canvas. I’ve no idea really what it’s about, I suspect it’s supposed to be about an experience of looking at some weave.

Bob Law was never fully part of any school or style and whilst he could be positioned at the margins of successive artistic movements, such placement was never permanent, convincing or comfortable. Whilst some of his works were conceptual in nature, he was seldom included in Conceptual art survey exhibitions. As he returned to sculpture in the early 1980s, this was not as part of the New British Sculpture. He was seen primarily as a painter in spite of his early sculpture (he was also far older than any of the other artists in that group). Despite this, Law continued to be productive and towards the end of the 1980s had two solo exhibitions in Karsten Schubert’s Charlotte Street gallery. Now may be a particularly good moment to look at Bob Law’s work again. The 1960s and 1970s have come under careful scrutiny. A new generation of critics and art historians are approaching this field, their thinking unclouded by personal acquaintance or agendas. At the same time the whole concept of artistic centre and periphery is under review and the idea of a master narrative is less dominant. Against this background there is the opportunity to reclaim the space Bob Law once so deservedly occupied. Helping re-establish this space is the purpose of this monograph. The goal is to document Bob Law’s career as extensively as possible and to provide archival information and contextual essays through which the works can be considered. We chose four authors, each of whom was asked to approach the subject from a different perspective. To this we added Richard Cork’s interview from 1974 to give a flavour of Law’s own voice and a recent text by Giuseppe Panza which provides the important collector’s view of the artist. The aim is to reconsider and to celebrate the work of Bob Law. Bob Law’s works are intense and demanding. They have a physical presence and an intensity that is entirely out of proportion to their actual scale, insistently demanding (and receiving) the viewer’s fullest attention. Coming across individual paintings, sculptures and drawings by the artist in group exhibitions or private collections is always a startling experience. Each work is a really a distillation of all those that went before. Law actually came closer to realizing his inner vision than he was ever, in his self-doubt and modesty sometimes, willing to grant himself. His struggle is our gain. 1 See Bob Law: Paintings and Drawings 1959–78, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 1978, unpaginated. 2 ‘Fyfe Robertson at the Hayward Gallery’, on Robbie, BBC, 15 August 1977 [television interview], transcript published in Art Monthly, no. 11, October 1977. Thankyou to Richard Saltoun and Karsten Schubert. Copyright remains with the authors, courtesy Ridinghouse. see 'profiles' and 'interviews' for more on Bob Law. The Bob Law monograph can be ordered from http://www.cornerhouse.org/books/info.aspx?ID=3294&page=0

|

|

|

character

and his idiosyncrasies make this inevitable. Listening to personal

recollections, it becomes clear that Law’s personal traits sabotaged

his professional relationships with the all-important supporting cast

of writers, curators, collectors and dealers. These traits were in

turn reinforced by the harsh cultural climate that surrounded him.

From today’s perspective it is virtually impossible to fathom the

difficulties a ‘hard line’ avant-garde artist faced in 1960s and 1970s

Britain; the sense of isolation and hostility with which he had to

contend. In the end any expression of support and kindness, so long

absent and longed for, when they finally came, only made him terribly

nervous. He dealt with such attention by provoking arguments and

splits that from the outset he considered inevitable.

character

and his idiosyncrasies make this inevitable. Listening to personal

recollections, it becomes clear that Law’s personal traits sabotaged

his professional relationships with the all-important supporting cast

of writers, curators, collectors and dealers. These traits were in

turn reinforced by the harsh cultural climate that surrounded him.

From today’s perspective it is virtually impossible to fathom the

difficulties a ‘hard line’ avant-garde artist faced in 1960s and 1970s

Britain; the sense of isolation and hostility with which he had to

contend. In the end any expression of support and kindness, so long

absent and longed for, when they finally came, only made him terribly

nervous. He dealt with such attention by provoking arguments and

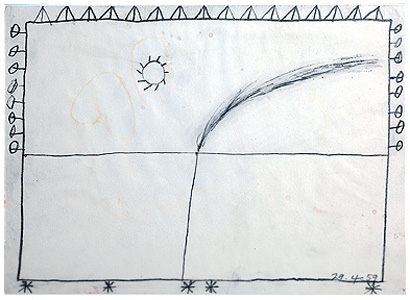

splits that from the outset he considered inevitable. Out

of Law’s interest in geometry and technical excellence came a pursuit

of absolute perfection in execution. He wrote in 1978 about seeing the

perfect work in his ‘mind’s eye’. His role as artist was to bring that

work into existence. Inevitably there would always be small flaws that

required correction to match this vision. The serial paintings can be

seen in this way as repeated attempts to eliminate flaws and achieve

perfection. There is a ‘trial and examination process in which the

artist is solely responsible to himself for the quality and conviction

of the work.’1 There was a dark side to this striving, inevitably most

works did not live up to expectation and were destroyed. With such

overreaching standards of quality, any sustained sense of achievement

ultimately eluded him. It was not just current bodies of work that

were subjected to such harsh critique. Law periodically returned to

his past to eliminate works that he no longer felt passed muster. As a

result, it looks as if his work suddenly appears at the end of the

1950s, seemingly fully formulated, without hesitation or gestation. No

juvenilia exist, except one small

watercolour that survives in the Prints and Drawings Collection at the

British Museum, possibly because it was safely out of the artist’s

reach. Of the celebrated Field drawings of that period (eg picture

above: Drawing 29.4.59), Law kept about twenty out of the

hundreds he produced. Throughout his career he continued to exercise

this editorial rigour; it was as if, for Law, the works were in a

linear progression towards an absolute so that the earlier attempts

were not required any more.

Out

of Law’s interest in geometry and technical excellence came a pursuit

of absolute perfection in execution. He wrote in 1978 about seeing the

perfect work in his ‘mind’s eye’. His role as artist was to bring that

work into existence. Inevitably there would always be small flaws that

required correction to match this vision. The serial paintings can be

seen in this way as repeated attempts to eliminate flaws and achieve

perfection. There is a ‘trial and examination process in which the

artist is solely responsible to himself for the quality and conviction

of the work.’1 There was a dark side to this striving, inevitably most

works did not live up to expectation and were destroyed. With such

overreaching standards of quality, any sustained sense of achievement

ultimately eluded him. It was not just current bodies of work that

were subjected to such harsh critique. Law periodically returned to

his past to eliminate works that he no longer felt passed muster. As a

result, it looks as if his work suddenly appears at the end of the

1950s, seemingly fully formulated, without hesitation or gestation. No

juvenilia exist, except one small

watercolour that survives in the Prints and Drawings Collection at the

British Museum, possibly because it was safely out of the artist’s

reach. Of the celebrated Field drawings of that period (eg picture

above: Drawing 29.4.59), Law kept about twenty out of the

hundreds he produced. Throughout his career he continued to exercise

this editorial rigour; it was as if, for Law, the works were in a

linear progression towards an absolute so that the earlier attempts

were not required any more. Hockney’s

failure to understand Law’s minimalism thus served to endorse

Robertson’s own assessment. If an artist like Carl Andre, thousands of

miles away, felt deeply upset about the infamous Tate ‘bricks’

scandal, it is hard to imagine the effect of Robertson’s attack on

Law.

Hockney’s

failure to understand Law’s minimalism thus served to endorse

Robertson’s own assessment. If an artist like Carl Andre, thousands of

miles away, felt deeply upset about the infamous Tate ‘bricks’

scandal, it is hard to imagine the effect of Robertson’s attack on

Law.