|

Cornwall 1947 -

1948 pt 1: Mevagissey and Newlyn

Kathrine Talbot

Kathrine Talbot

(1921 - 2006) was the pen name of novelist Ilse Barker. Ilse was married

to Kit Barker - artist-brother of George Barker the poet - and lived in

West Cornwall in the immediate post-war period. Her memories of that

time, and of friends like W.S. Graham, David Haughton and Bryan Wynter,

were first published in 1994 in a limited edition booklet.

Sometime in the spring of 1947 Bryan Wynter

bought an old Ford van in London and asked a friend, Bill McKenzie, to

drive it down to Zennor for him. Bryan had fairly recently begun to live

at Carn Cottage, high above Zennor, overlooking the bay between Zennor

and St. Ives. Bill, possibly because he was uncertain of the road or the

dependability of the Ford. for the company, or simply out of friendship,

asked Kit to go down to Cornwall with him. I don't know how long they

stayed with Bryan (the Carn had a living room and one tiny bedroom), but

while they were there they saw an empty Sail Loft in Newlyn which was

for rent for five shillings a week and decided to rent it and live in

it.

Back in London, Bill and Kit found others who wanted to join them in

Newlyn, and after a while they began to make their way there, probably

Bill first on his motorbike with Graham Court who was also a painter.

David Duff, one of the more permanent tenants, may also have gone down

at that time. Kit was living at home and had no money for such a move.

It was Monica Humble, the youngest of his three elder sisters who, later

that summer, made it possible for him to go to Cornwall. Her husband

Bill had just been in Paris on business, something almost unheard-of so

soon after the war, and had brought her back some elegant French

lingerie, rather different from our 'Utility' panties and bras. Monica

sold this precious present and gave Kit the money.

The four tenants of the Sail Loft were joined by various friends for

longer or shorter stays. David Archer was certainly there for a short

time, also Kit's brother George and his girlfriend Cass. Michael

Hamburger, whom Kit had known in the army, passed through. Some of the

visitors brought a little cash, otherwise there was none. I don't know

how the rent got paid. They all went down to the quay to fish, and the

good natured fishermen, coming in with their catch, gave the pilchards

for bait which ended up in the frying pan. When a fish-lorry drove past

him one night, Kit hung on to a tail sticking out at the back, and they

had turbot for a night or two.

David Archer, always generous and at that time still affluent was

certainly, the provider for a time, and must have been a loss when he

left. Kit asked the fishermen for work, but there were no jobs. For a

while there was a scheme for buying a derelict boat and going fishing,

but this came to nothing. David Duff and Graham Court got the occasional

cheque and food parcel from home.

In the meantime I had been staying in Mevagissey, to the east of Newlyn.

A number of writers had made their home there. Among them was W.S.Graham

and Nessie Dunsmuir who were living in a house belonging to Frank Baker

(who was away for part of that summer and whom I knew from London). I

made friends with them, and they found me lodgings in their street with

a Miss Husband. Another writer, Louis Adeane, had a cottage a few miles

inland in a little wooded valley. Still in his twenties, he was already

a published poet and had a job as 'reader' for a publishing house. I was

terribly impressed. Near him lived Derek Savage, his wife Connie and

their children (I had met the Savage family in their Cambridge cottage

in the war). Derek had been publishing poetry, especially in the U.S.

literary magazines, since the '30s. He, like Louis, was a pacifist. They

had been permanent residents for some time.

George Barker and Michael Asquith came to stay for a while as did the

painter Keith Vaughan. David Archer, patron of impecunious poets, was

there most of the summer. There was a young man called Michael White.

The young American writer Mary Lee Settle and her poet husband Douglas

Newton found lodgings and talked of staying.

Mevagissey was at that time an unspoilt fishing village with narrow

streets and hardly any traffic. The road came down the valley from St.

Austell, then went west towards Truro, but the streets above the harbour

were too narrow for cars, running down the hillside with houses on one

side, a wall on the other. When one wasn't doing anything else, one

leaned over this wall watching the tide going in or out, boats being

cleaned, 'toshers' being made ready for mackerelling. Fishermen stood

talking by their boats in groups or sat sunning themselves on a bench on

the quay, people walked on the double arms of the seawall. There were

greedy seagulls waiting for tid-bits or swooping to pick up what was

revealed as the harbour emptied at low tide.

There were two guest houses up on the other side of the harbour (I was

told that it was called the 'money side' in contrast with the 'sunny

side' where most of the fishermen lived), but there were scarcely any

tourists, for the war was so recently over and petrol still rationed. At

the hops in the village hall on Saturday nights one occasionally met

someone from London or Birmingham, but the little harbour-side cafe

served their crab sandwiches and Camp Coffee mostly to permanent

residents and the day trippers from nearby Cornish towns.

The great talking-point in the village,

everyone's boast, was the making of 'Johnny Frenchman,' a film shot in

Mevagissey with an Anglo-French cast. Everybody had a story to tell of

Francoise Rosay or the other stars, of the money they'd all made! It had

been their annus mirabilis - French brandy had flowed in the pubs.

'Everybody' had had a part as an extra. Both the film's Cornish fishing

village and its Breton counterpart had been shot in Mevagissey, and I

was told that, for the French scenes, a (cardboard?) pissoir had been

erected in the square, hiding the war memorial.

We had a good time that cloudless summer, spending our days on the beach

and evenings in the pub playing darts for pints. On Saturday nights we

went dancing. The 'locals' kept themselves to themselves, but the

fishermen were friendly; we were soon on Christian name terms, and they

would partner us at darts and buy one a beer. The wives never came to

the pub, one only saw them with their husbands and children on Sundays

on their way to and from chapel.

We had little money but we shared what we had. Nessie received ten

shillings sickness benefit, Sydney (mostly called 'Jock' at that time)

went long-lining with the fishermen whenever an extra hand was needed.

The Mevagissey fishermen did not go fishing with nets but with lines to

which hooks were attached every few feet. The lines were neatly curled

in tubs, and on the way to the fishing grounds were baited with pieces

of pilchard. Arrived at their destination, the lines were cast between

marker-buoys, then, after an hour or two, hauled in with a catch of,

mostly, whiting and dogfish, some cod and haddock, an occasional

monkfish or John Dory, and a few crabs. Sometimes the hooks came up

empty, sometimes every hook had a fish on it. It must have been hard

work, pulling in the heavy lines in a strong swell, and heaving them on

board where the fish struggled and flapped on the deck. By the time the

boats returned to the harbour, the fish were sorted and ready to put

into baskets.

Having learned of my parents' death in Hitler's camps, I had brought

what I had saved over the years against their possible return (as well

as a little money from the sale of my mother's jewellery), when, after

trying to write a novel and short stories at night, I decided to come to

Cornwall to write fulltime. I allowed myself £3 a week (my room cost

£1), and did not realise that I thus acquired a reputation as a young

woman of means.

We pooled our rations, and I had most of my meals with Jock and Nessie.

The fishermen, returning from their long-lining in the morning or late

afternoon, often gave us fish, especially crabs and the despised (!)

monkfish. We would buy a joint for Sunday and take it to the communal

oven. I think it cost 3d to put it among the villagers' joints and

pasties, and I loved to go and collect it in the tin, surrounded by

lovely roast potatoes, and walk with it down the street. Even in 1947

this seemed an archaic, an almost heraldic thing to do.

Many of us were, I think. still recovering from the war years. I felt

later that that summer made up for the carefree student days I'd never

had, and gave me the holiday which, in war-time London, was no more than

a rainy week a year, not enough to get over the strain of air raids and

anxiety. Though I had come down to Cornwall to write a novel, I left the

typewriter unopened on top of the wardrobe. People were easy to get on

with. We would set off for the beach east of Mevagissey every morning,

walking down to it by a steep path. There we swam, dived from nearby

rocks. I sometimes went for a walk with one or another of my new

friends, going west through Portmellon and Gorran Haven where there were

writers to visit, and on to St Michael Caerhays, a magical place then

home climbing across the back of the Dodman. We talked endlessly of

books, writing, painting and poetry. If we had problems that was not

apparent. I accepted everybody's way of life, and made myself useful,

typing some of Sydney's poems on the Baker's kitchen table, cutting the

men's hair, a skill I acquired on Mevagissey Beach and continued to

practise through my long married life. I admired the domesticity of

Louis Adeane who had parted from his wife and led an exemplary batchelor

existence in his cottage. I took for granted Jock and Nessie's

unsanctified union as well as the homosexual relationships around me and

David Archers pursuit of the handsome young fishermen who played

water-polo in the harbour in dashing leopard patterned trunks.

Unsophisticated and possibly unobservant, I did not think at the time

what a handsome group they made, Louis with his dark eyes and great

tangle of black locks, Sydney taller, with red curly hair, his sharp

eyes contrasting with his clown-cracking smile. Nessie was demurely

beautiful, wore a skirt made from a paisley shawl. She joined in most

when it came to the singing. George, looking like an Irish labourer in

his cap in the pub, looked like a Greek god on the beach. Michael,

another redhead, was tall and thin, but while Sydney was ruddy,

Michael's skin was pale. Mary Lee appeared strong and handsome, (she'd

been in the American army), determined beside her less substantial Den.

If you were a poet you lived - somehow. I was prepared to find poets

dedicated to their art, licensed to be self-centred, penniless. About

painters I knew nothing. When George spoke of his painter brother Kit,

about to arrive in another part of Cornwall, I remember wondering what a

painter lived on. I had met Yankel Adler, but he was older and

established, his work seen in the galleries. George suggested I meet his

brother once he was installed in the Sail Loft in Newlyn.

The painters and poets who lived in St. Ives, Newlyn and beyond had

peopled many conversations among the Mevagissey Bohemians. Bryan Wynter

and Susan Lethbridge had become familiar names. The older painters like

Ben Nicholson were, of course, already famous. David Wright, coming from

St. Ives one day, brought the latest gossip. I met him rising out of the

harbour like some sea-creature, shaking the water out of his already

grey hair.

While we swam from the beach most of the time, one could save the long

walk and climb by having a dip in the harbour. This was not allowed on

Sundays so as not to disturb the sensibilities of the chapel-goers.

Michael Asquith left, then George Barker, and some weeks later I had a

postcard from Kit. Could he come over from Newlyn? I stood in the narrow

lane leading down to the bus stop and watched the people walking up,

wondering whether I would recognise him, wondering what we would say. In

the end it was easy to pick him out. He was like George and yet not, had

lighter hair, chestnut brown, and more of it both on top and, less

acceptably, curling over his collar. His eyes were blue but not piercing

like George's, and he wore horn-rimmed glasses. I did not notice that

one was a glass eye, even though his brother had told me of the fencing

accident that had cost him his eye. I think I considered a one-eyed

painter too bizarre, and George was known to 'exaggerate.' Kit wore a

brown corduroy jacket and corduroy trousers. He was quiet, but we were

not shy with each other.

Miss Husband had a vacant room at the top of her house where he could

stay. We went to the pub that evening, and Kit met the rest of the gang,

some of whom he knew from London. While George had always referred to

him as 'Kit,' I noticed that some of his London acquaintances called him

'Gordon.' This was his given name, but the family had always called him

'Kit,' and, though earlier paintings of his signed 'Gordon Barker' have

now been found, he always signed himself Kit Barker from the Cornish

days on.

He stayed for a few days, came back and forth for a while. When Frank

and Kate Baker returned with their two little boys, Sydney and Nessie

moved into a tiny cottage in the interstices of Mevagissey back streets.

We spent a week or two energetically renovating the damp and derelict

building. (oh, the accumulations of old wallpaper!). Miss Husband had

told me that I would have to move out in the 'season,' and the Bakers

let me have a room in the next door cottage they had just bought. Kit

joined me twice, and the two of us painted the woodwork of this new

acquisition a satisfying vermilion.

By then it had become clear that the other inhabitants of the Sail Loft

would be leaving, and Kit suggested I come over to Newlyn once he was on

his own and we'd 'see how it went!' Kit wrote every day, I was anxious

to move in, but there were many delays (David Duff, on the day he was

due to leave, set his hair on fire while lighting the primus and had to

recuperate), but finally the day came when I took the bus and train to

Newlyn to join Kit.

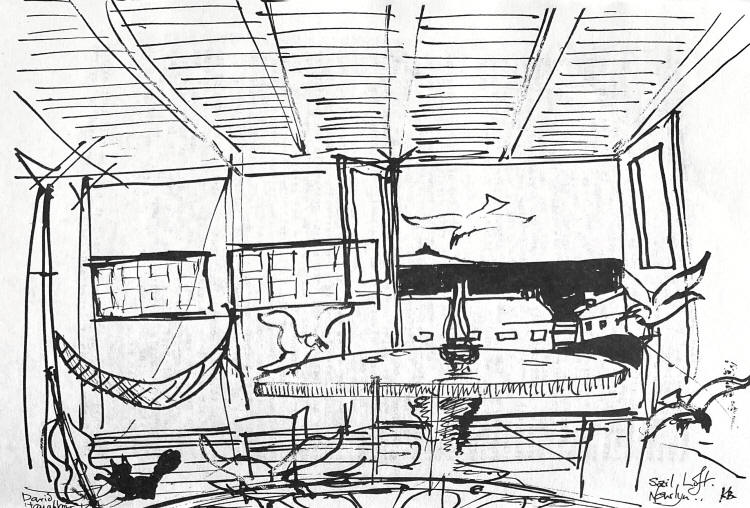

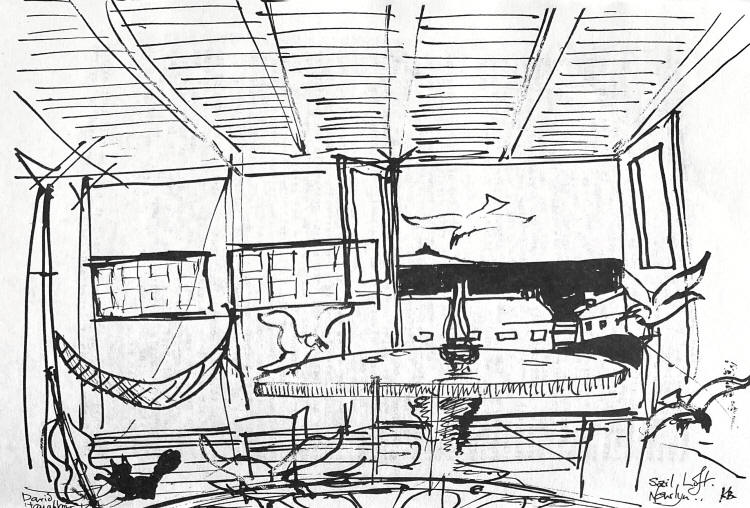

The Sail Loft, up a steep lane just off the road that skirts the

harbour, was a large and lofty place (we used to say you could drive a

bus round it) where sails were once stored and mended. Though you went

straight in from the lane , it was the upper part of a former boathouse.

Kit had stretched a few old sails between the uprights supporting the

roof-beams, their canvas discoloured through the years, the cream

turning grey, the terra-cotta salmon-pink. The building was flat-iron

shaped, the roof coming to an intricate and not central point high up.

When we looked after David and Lali's kitten for a few weeks it climbed

up the wooden posts at night and had a fine game running along the

crossbeams, just beyond our reach.

There was a round table and a few kitchen chairs, one chair usually

turned to Kit's Dulcitone. This charming little musical instrument,

painted white with relief medallions, its keyboard two and a half

octaves, and the keys sounding on tuning forks, was Kit's most precious

possession. He played early tunes, Purcell, the Earl of Salisbury's

Pavane, or some of the family folksongs. There was a chest with a primus

on top a single comp-bed. David Archer, I was told, had slept in a

'hammock' made of old fishing nets and had slowly oozed out of the

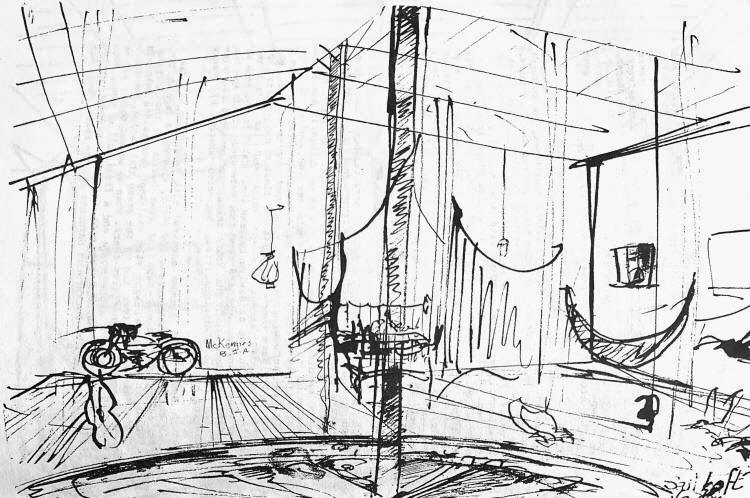

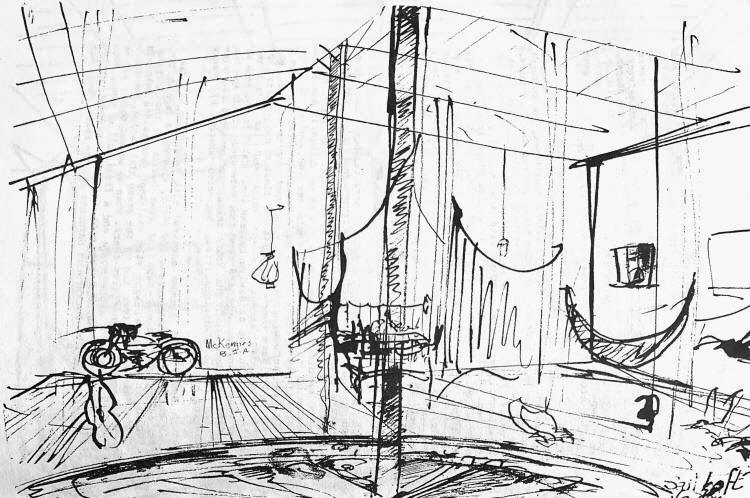

bottom. but never quite fallen through. There was also Mckenzie's BSA.

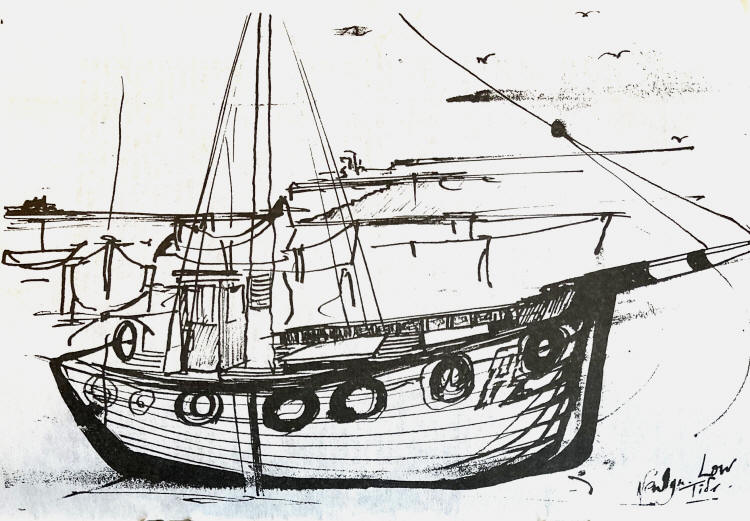

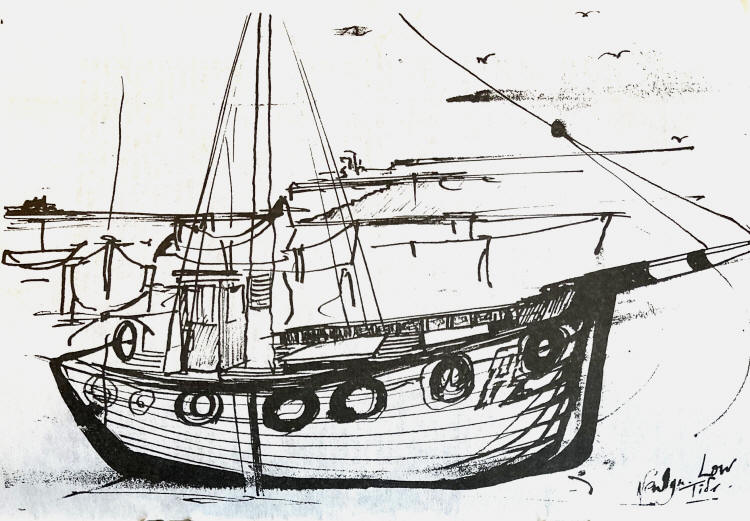

When, in 1985, Kit made a series of drawings 'Recollections of Cornwall'

some of which illustrate this text, the motorbike features in one of the

Sail Loft. So does the I carpet' Kit painted on the floor. It was

handsome, in primary colours, round, vaguely Persian, perhaps eight feet

in diameter. He always said that the postman was afraid to step into the

loft, thinking the carpet was a pentagram.

On the side overlooking the harbour were two huge double doors which

opened onto a yard about fifteen feet below. The doors were kept open

most of the time while the autumn continued warm and sunny, and seagulls

came in to scavenge. The view of Mounts Bay was magnificent. We weren't

high up enough to watch the business of the harbour but could see the

loading of large vessels at its western end towards Mousehole where

there was a quarry. The harbour itself, when one went down to the quay,

was always busy. Here there was a fishing fleet of long-liners, but

there were also larger trawlers which went far afield and filled up with

ice at Newlyn to keep their catch fresh. Some of them were French, and

there were some pubs where French was the predominant language. One

heard tales of fights and rivalries between the two nationalities, but

also stories of brandy changing hands.

Though Newlyn was a town compared with Mevagissey, it was a very small

one. There were a few shops, a Co-op, a cafe or two, the Sailor's

Mission, pubs and fine houses on the 'Parade' running to Penzance, some

with well-kept gardens and palms in front. Most of the town ran up the

steep hill behind, but there were also still open fields there. When we

walked to the pub at Paul, we crossed a stone stile and a field full of

cows. From there you could see the bay with St. Michael's Mount in the

ladle, and in the background Marazion and the Second World War

battleship 'Warspite' on the rocks. For serious shopping and the cinema

we walked the mile into Penzance.

After a week I returned to Mevagissey to collect my luggage and buy

various necessities. I'd made friends with a junk dealer there, and he

sold me a beautiful brass double bed and a fine chair and had them

delivered to the Sail Loft.

But the BSA (motorbike) remained for a number of weeks. McKenzie (now

living in an inland cottage) used to come in and work on it at all times

of the day. It was in any case a pretty public place. When the postman

delivered a parcel (the ex-residents and Kit's mother sometimes sent

food), he would open the door from the lane and say good morning to us

as we lay in bed. When the BSA was finally fixed, McKenzie started it up

and roared out of the same door!

One of the most potent memories of those early Newlyn days is my first

meeting with David Haughton and his Hungarian girlfriend Lali. It seems

so strange now, but at that time it was a commonplace 'treat' to have

tea, wherever one lived, in the local cinema's tearoom, usually painted

pink and cream, Presumably we had walked into Penzance and were having

tea before walking back. We had settled at a table, when Kit saw his

friends. We went over, and Kit introduced me. I was stunned by Lali's

beauty, her long black hair and fine oval face with very dark eyes.

David, small and slight, with sharp features and short brown hair,

looked intelligent and lively, Kit told me that he had studied at the

Slade, and I was impressed. I am pretty sure the fact that Lali had also

been a slade student was never mentioned, and she did not tell us until

much later that she did an occasional drawing. David and Lali lived in a

cottage on the moors at Nancledra, more or less half-way between

Penzance and St. Ives. We often went out to see them after this and

sometimes stayed the night. There was a bus from Penzance followed by

what seemed to me a very long walk through farm-land and over moors. I

thought their cottage very romantic. There were few amenities. Water had

to be fetched from a stream, there was a privy round the back, cooking

was done on primus and paraffin stoves. At night an oil lamp lit the

living room, and one went to bed with a candle. David always had several

paintings going, so the living room was full of the paraphernalia of

painting: canvases leaned against the walls, and a lovely smeli of oil

paint mixed with the cooking smells.

I was deeply impressed by David's work. He was at that time painting

portraits of Lali, often against vivid strips of material, red and

green, blue and yellow. His style was much influenced by Wyndham Lewis,

but I didn't know that then. I admired the way his subtle distortion of

her features changed her beauty without detracting from it. Later he

painted the rows of cottages which became typical of his Cornish work,

and there was also a period of paintings of brightly coloured farm

machinery, also greenhouses and cold frames with greenery and the splash

of scarlet geraniums or tomatoes.

David was a hard worker. Apart from his paintings I particularly

remember an offset drawings of Lali which he sold to a patron in London

for what seemed a good sum. Kit told me that he had a tiny income from

his mother. Lali went waitressing in St. Ives, taking that long walk

followed by a bus journey several days a week. This was the accepted

pattern for many painters at that time. Unless you had a sufficient

private income or family help, the wife or girlfriend would go

waitressing or find seasonal farm work.

Though there was neither heating nor water (let alone lavatory

facilities) at the Sail Loft, we managed happily right through into

November. As it got colder, we spent most evenings at the pub, the

'Fisherman's Rest,' the 'Tolcarne,' or the pub at Mousehole. We didn't

know many people. The only Newlyn painter I remember Kit speaking of at

the time was John Wells, but he was reclusive, and I did not meet him

then.

When we walked back from Mousehole in the autumn dark, we would sing to

help keep up a brisk pace. I had been familiar with communal singing in

wartime. At Mevagissey I had been introduced to a different kind of

singing. Nessie had a fine voice and sang Scottish and Hebridean songs,

George sang Irish songs and the folksongs he had brought back from the

U.s. He accompanied himself on an imaginary violin, favoured 'Careless

Love,' 'Foggy Dew' (not yet made popular by Britten), and regretted

Kit's absence when he sang 'The Royal Blackbird.' Kit too had a large

repertoire, the finer voice of the two. Later he was to sing folksongs

on WQXR in New York! I learned many of the 'family' songs then,

especially loved 'She Walked Through The Fair' and 'The Snowy-Breasted

Pearl.' Singing with a pint in your hand by the fire was part of

everyday life.

By now I was working on my novel and Kit painted, often on pieces of

wood picked up on the beach or in town.

When we had met in Mevagissey, I had wondered, of course, what Kit's

painting was like. Brought up to museum visits and an interest in art, I

had gone to the London galleries in and just after the war and seen the

paintings of Paul Nash and Piper, Sutherland, Tunnard, MacBryde and

Colquhoun, Ayrton and Lucien Freud. I had bought postcards and the

occasional Medici print. Kit, painfully shy, (he found it difficult to

go into shops) did not talk about painting; his own or other people's.

Acquiring a few sheets of paper and a pencil, he made a few drawings in

Mevagissey. They were of 'Amazons,' schematic 'jointed' female fighting

figures. Since I had recently been involved with the Freudians, working

for the West Sussex Child Guidance Service, I was more concerned with

their content than their execution. When I got to the Sail Loft, there

were no paintings for me to see. Kit had no money to buy paints or

canvas. There was no easel. If, naively, I thought that painters drew

'all the time,' this was a habit Kit only acquired later in life when he

filled his many sketchbooks with drawings and watercolours of places he

saw, of figures, 'versions' of favourite famous paintings or Japanese

prints, flowers and fruit, small objects like feathers and shells, and

recollections of the past, making drawings on the spot or in his studio

until late into the evening.

Click here for pt 2

Originally published in 1994 by The Book Gallery as 'KIT BARKER - CORNWALL 1947 - 1948 - Recollections of Painters and

Writers'. Please get in touch if you have a copy of this limited edition

booklet and are able to provide us with the missing last page!

See

interview with Joy Wilson for more on Mevagissey writers:

http://www.artcornwall.org/interviews/Joy_Wilson_Colin_Stanley2.htm.

David Tremlett too has his own

memories of this part of Cornwall:

http://www.artcornwall.org/interviews/David_Tremlett.htm

This

interview with Michael Bird has more on Bryan Wynter:

http://www.artcornwall.org/interviews/Michael_Bird_on_Bryan_Wynter_and_St_Ives.htm

An

obituary for Isle Barker is here

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/jun/03/guardianobituaries.germany

With thanks to

Blair Todd |