|

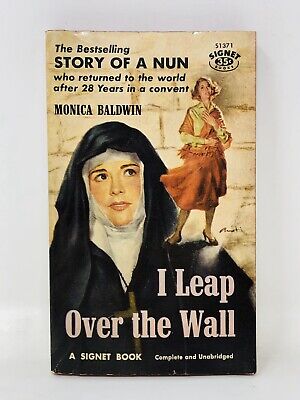

I Leap Over the Wall (extract)

Monica Baldwin

'I Leap Over the

Wall' was published in 1949.

Its author, Monica Baldwin (1893-1975) had lived as a strict Augustinian

nun for most of her life, but after leaving her

nunnery she moved

to Cornwall to live in the harbour at Lamorna in 1946. Shortly after

Ithell Colquhoun acquired Vow Cave, Monica gave a manuscript copy of

the book to her, and in 'The Living Stones'

Ithell describes reading it 'with

great admiration and amusement'.

Cornwall, it appeared, was only prevented from

being an island by the little three-mile neck of land between

Severn-mouth and the squashy bog in Morwenstow from which the Tamar

oozes. North, west and south, the Atlantic breakers roar or ripple

according to the season.

To me, this seemed

almost too good to be true. You see, I have always thought of an island

as an ideal setting for romance (Shakespeare knew it when he chose

Prospero's Isle as a background for The Tempest). I felt, too, that it

helped to explain the 'differentness' of Cornwall from the rest of

England. She was more than just one more lovely English county; she was

a country apart, whose people had every right to call folk from the

other side of Tamar 'foreigners'.

I discovered, too,

that even the dry geographical bones of her were shrouded with romantic

legend. There was the primeval forest that had been swept away when the

sea rushed in and overwhelmed Mounts Bay; the shifting sands of the

north coast that had piled themselves above the ancient churches. And,

loveliest legend of all, lost Lyonnesse, whose lands once stretched from

where the Longships Lighthouse stands to-day over to the Scilly Ises and

eastward right away to Lizard Point. I discovered, too,

that even the dry geographical bones of her were shrouded with romantic

legend. There was the primeval forest that had been swept away when the

sea rushed in and overwhelmed Mounts Bay; the shifting sands of the

north coast that had piled themselves above the ancient churches. And,

loveliest legend of all, lost Lyonnesse, whose lands once stretched from

where the Longships Lighthouse stands to-day over to the Scilly Ises and

eastward right away to Lizard Point.

One writer, suggesting

that the vanished Cassiterides were once a part of Lyonnesse, insisted

that, if you listened breathlessly on those rare still days when no

waves disturbed the sea, you could hear drowned church bells chiming in

the water far below.

Her history I found a

trifle disappointing. There seemed so little of it. Or, possibly, I got

hold of the wrong books. Anyhow, Cornwall appeared to have had next to

no contacts with the history of England. As 'Q' pointed out, a few

sturdy insurrections against the imposition of taxes or the 'reformed'

liturgy—two or three gallant campaigns in the fated cause of Charles I,

and—of course the great revival of religion led by Wesley, made up most

of the written tale.

To atone for this,

however, every stone and mound held hints of her unwritten story. And it

was this which, above all things, thrilled and stirred my

imagination. This kind of history was not to be learnt from books. You

had to get into actual contact with the place itself; with the tombs,

long-stones, dolmens, barrows and stone circles set up more than six

thousand years ago by an unknown race.This was the secret Cornwall of

the hill-tops, moors and ruined cliff-castles, all older than the

earliest records that exist.

Instinctively I knew

that the Old People had left something of themselves behind them; that

each grim monolith contained its own dark life. In those fantastically

shaped stones where so much blood had been outpoured, often in human

sacrifice. 'Something' still lived, mysteriously imprisoned -

'Something' which could only communicate itself if one were able to

receive what it had to give.

I must, I felt, I

absolutely must get down there; preferably to that weird, rather

menacing neighbourhood inland from Morvah and Land's End. For I felt

sure that if I could only soak myself sufficiently in the atmosphere of

such places as the Stone Circles of Tregaseal, or Carn Kenidzhek-'the

Hooting Cairn'—among whose boulders and holed stones the spirits of an

even older people than the ancient Celts still lurk—well— I should have

no difficulty about 'tuning in' to their vibrations...

------------

The very girders in

the blitz-scarred roof at Paddington appeared transfigured: I saw them

as fairy arches through which one passed out into the realm of gramarye.

'Gramarye.' Yes: that,

undoubtedly, was the word for it. And on that particular morning, it was

everywhere. Now and again I had a definite physical feeling that it was

beginning to break through from the invisible territory which I was

trying to invade.

I settled myself into my corner and looked out

through the broad plate-glass window of the Cornish Riviera express. If

ever a magic casement, I reflected, had opened over a perilous fairy

sea, it was to-day....

Blue skies and flowers

in sunskine on the cliff-tops, with spars from a shipwreck floating in

the cove below...to me that spelt the double personality of Cornwall.

Half her charm lay in the number and unexpectedness of her contrasts.

She communicated herself in a series of odd little shocks.

If I had to pick out

the pair of contrasts which seemed to me the most characteristic of the

double spirit which meets you at every turn in Cornwall, I should have

no difficulty. I felt it long before I actually arrived. It was the

subtle, almost sinister Tannhauser struggle between the two motifs of

paganism and Christianity.

On the one side, you

had the saints and hermits who, in the early centuries, had floated

across from Ireland on a spread cloak or millstone of miraculous origin.

From the little wave-side churches in the sand, from the holy wells

beside which they had dwelt and to which they had given their names,

rose their chant of prayer and praise strong and clear as a pilgrims'

chorus down the years. And on the other ... well, you might say what you

liked.... But there was no denying it; from among the trailing ivy and

the gnarled tree-trunks in the wooded valleys, from the hillside

boulders and the stone circles and the ancient burial-mounds, on a

spring morning or when the moon was full at midsummer, the faint

far-away fluting of the pipes of Pan could still be heard.

I kept my nose glued

to my magic casement. But it was only after the train had rushed through

Reading that the fun began.

It started with a

sudden deepening of colour. The earth reddened. The fields grew lush and

deep. The sky flamed to a more ardent blue. Streams and pools appeared

and the woods and copses changed from burnt olive to emerald and gold.

At Exeter there was a

long stop: long enough to let me hear for the first time the mellow,

deep-voiced dialect of the West country. I liked it better than any

speech I had ever heard.

After Exeter, a new

rhythm crept into the melody. It was the rhythm of the sea. Along the

miles of biscuit-coloured sand that stretch between Teignmouth and

Dawlish, slow waves broke, in long ruled lines of silver. The milky,

egg-shell blue of the water looked faint and feminine against the dark

sorrel-red of the tunnelled rocks through which the train occasionally

boomed. The sea was so close that now and again it seemed as though the

waves would dash themselves across the line.

Plymouth-squalid

beyond words, with its mean slums, war-wreckage and appalling

devastation-was an unwelcome reminder of the civilization from which one

was in flight.

'Look,' somebody in the carriage called out

excitedly, 'we're just going over the viaduct at Saltash!' And I knew

that the gateway into the enchanted country had been reached.A moment

later and, with a rattle and a roar, the train was through it.

I was in Cornwall at

last.

----------------------

The first thing that

impressed me about Cornwall was that the landscape had grown sterner.

Instead of the rich red soil and moist pastures of Devon, there were

steep hills with scurrying streamlets and valleys filled with rocks and

under-growth. Now and again the train rumbled across a viaduct and,

looking down, one saw the tops of trees far down in the gorge below.

Here were the forest

tracks along which Sir Tristram must have ridden up to Camelot: the very

woods, perhaps, through which King Mark fled, chased by Sir Dagonet the

Fool....The whole country gave one a vague impression that it had lived

through thrilling happenings. The very air was thick with story. It blew

in through the open window like a breath of incense out of the forgotten

past.

It was before Truro that a Cornish

fellow-traveller started reciting the station names to his companion.

After that, I knew for certain that I was in a foreign land. Menheniot;

Double-bois; Lostwithiel; Carn Brea; Gulval. ... Here was gramarye

indeed. Only to utter such words of power should surely be enough to

summon buccas, spriggans, piskies from their lairs.

I had chosen this

particular region of Cornwall because all I had read of it suggested

that it would be the perfect setting for my Cottage-in-the-Clouds. It

bulged with ancient British villages. It crawled with prehistoric odds

and ends. It contained more holed-stones, fogous, cromlechs, monoliths

and stone circles than any other part of Cornwall. Mysterious presences

and apparitions haunted it.

People said that it

was the last stronghold of the Cornish fairies. And in bygone days, it

had been the chosen dwelling place of giants. Could one ask more?

My plan was to explore

the countryside in the hopes of discovering a cottage. Failing this, I

meant to buy a plot of land and build. It was late afternoon when my

dragon-drawn chariot at last pulled in to Penzance. And—it was raining.

But what rain! To me it seemed almost lovelier than sun-shine. The sky

was a misted opal and the breeze from the sea like wine. And just across

from Marazion, shrouded in veils of faintest lavender, St. Michael's

Mount floated above the water, a dream palace on a fairy isle.

---------------------------------

The cottage was perched on

a narrow terrace half-way up the cliff-side. A white gate led into a

minute cliff garden, so small as to be almost like a shelf. In the midst

of this the house was planted, its long, lean-to roof almost hidden by a

windscreen wall whose crenellated top gave it the appearance of a

fortress on a Lilliputian scale.

'Well, it's certainly small enough,' remarked the driver. It was indeed.

In fact, it was the smallest house I had ever been inside. The

living-room was simply the frame for an enormous casement window that

looked out across the cove on to the sea. Another even smaller room

adjoined it, used, apparently, for kitchen, bathroom, lavatory and

store. There were no shelves or cupboards anywhere and the 'kitchenette'

mentioned in the advertisement had apparently been used as the kennel

for a dog. The walls of the living-room, instead of being papered, were

hung with silken taffeta attached to wooden frames. The design was of a

forest glade with bluebells growing beside dark water under shady trees.

It made one feel as though one were standing in a fairy forest shut in

by trees and flowers instead of walls.

'It's heaven.' I murmured the words rather quietly, in case the driver,

who had just returned from examining the drains, should hear. 'They seem

Okay,' said the driver, without enthusiasm. 'But the garden's no larger

than a piece of toast.'

I followed him into it. It was hardly more than a ledge of granite. Yet

it had vast possibilities. At the far end, the cliff rose steeply behind

a thicket of blackthorn, continuing like a high wall round the back of

the house.

'I like this corner,' I said, peering through the blackthorn to where

bits of the granite rock-face were still visible. 'If all this stuff

were cut down, one could strip the cliff and make a marvellous

rock-garden.

We returned to the cottage. 'I expect I shall buy it,' I announced in a

voice which perhaps, in the circumstances, may have sounded

over-enthusiastic. The driver's expression of faintly amused disapproval

was a little dampening. He said, Well, of course, that was for me to

decide. He would not presume to give advice.

After further poking and prying we locked the door and I went round to

take a last look at the view from the garden. More than ever my

shoe-laces felt as though they were tied to the ground beneath my feet.

'It's like the cell of a medieval hermit,' I reflected. 'It's my

Cottage-in-the-Clouds come down to earth. It's so perfect that it might

have been built on purpose for me. In fact, I believe it was. ..

My heart had begun to thump with a strange excitement. Suppose this were

to be the end of all my voyagings and ventures? Well-why shouldn't it?

After all, the decision lay with me. We drove back from Trevelioc to

Penzance in silence.

In Market Jew Street, I got out and telegraphed to the agent that I

would buy the house.

|

I discovered, too,

that even the dry geographical bones of her were shrouded with romantic

legend. There was the primeval forest that had been swept away when the

sea rushed in and overwhelmed Mounts Bay; the shifting sands of the

north coast that had piled themselves above the ancient churches. And,

loveliest legend of all, lost Lyonnesse, whose lands once stretched from

where the Longships Lighthouse stands to-day over to the Scilly Ises and

eastward right away to Lizard Point.

I discovered, too,

that even the dry geographical bones of her were shrouded with romantic

legend. There was the primeval forest that had been swept away when the

sea rushed in and overwhelmed Mounts Bay; the shifting sands of the

north coast that had piled themselves above the ancient churches. And,

loveliest legend of all, lost Lyonnesse, whose lands once stretched from

where the Longships Lighthouse stands to-day over to the Scilly Ises and

eastward right away to Lizard Point.