|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Diagrams of whose Love? Ithell Colquhoun and Francesc d’Assís Galí Richard Shillitoe The retrospective exhibition of the work of Ithell Colquhoun held at Tate Britain (13 June – 19 October 2025) coincides with a retrospective exhibition of the work of the Catalan painter Francesc d’Assís Galí held in the Museu Nacional d’art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 20 May – 14 September 2025. This article takes advantage of this coincidence to discuss the rather unlikely relationship between the two artists.

During the early years of World War II, artist, writer and occultist Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988) was obsessed with sex. Not simply sex as a physical act between human beings, not simply sex for pleasure or sex for procreation, but sex as a pathway to spiritual enlightenment, sex as a magical ritual and sex as a route to union with the Divine. In truth, she was obsessed with sex all her life, forever finding penile and vulvic forms everywhere she looked in the natural world: caves, hills, rock stacks, stalactites, all were grist to her animistic mill; her belief that all of nature, even the apparently inanimate, is suffused with a God-given generative life force that links and binds them. But, for a short spell - roughly from 1940 to 1942 - her interest became much more focused. It concentrated upon the conjunction between human bodies that, according to certain occult teachings, can result in a profound spiritual transformation. It was the subject of over a dozen watercolour paintings either titled, sub-titled or inscribed “Diagrams of Love” and a similar number of closely related works. It was the title she also gave to two lyrical and sometimes enigmatic poetic sequences. Alongside these are numerous drawings, sketches and watercolours that detail the performance of sex acts with considerable intimacy and sometimes with an enviable degree of flexibility. It all forms a distinct body of work: highly erotic, highly individual and with a high spiritual purpose. They combine personal symbols with Christian imagery, all directed towards the goal of overcoming the duality of the two separate genders. The significance of this is that once prelapsarian wholeness has been achieved, the way will be open to convergence with the Divine. It is not, by any means, an original quest – it is the theory underpinning much of alchemy – but, as in so much of what Colquhoun did, her methods are unique to her.

fig. 1.

When considering the inspiration behind these works Amy Hale points out in her book, Sex Magic,[1] that it would be to trivialise Colquhoun’s spiritual purpose to claim that she was inspired by physical desire alone, or passion for an earthly lover. However, as the flurry of activity obviously occurred within the context of her daily life, it is a legitimate question to ask how far her life experiences and her occult purpose interacted. It has not been commented upon elsewhere, but Colquhoun’s work on “Diagrams of Love” closely coincided with the time when she was in a rather unlikely relationship with an exiled Spanish artist and politician, Francesc Galí. He seems an unlikely muse and their affaire is barely known. It is the subject of the present article.

The arrival of Galí in London Francesc d’Assís Galí, (1880-1965) also known as Francesc d’Assís Galí i Fabra, was a well-known artist and politician in his native Catalonia. In addition to easel painting he was an accomplished fresco painter and had been artistic advisor to the 1929 Barcelona World's Fair. He painted in a style known as Noucentisme, a Catalan cultural movement which favoured a return to classical principles of purity and balance over Modernism. Galí, like many Noucentrists, supported Catalan independence. He became increasingly engaged in politics and during the Spanish Civil War served as the Republic's Minister for Fine Art. After the defeat of the Republicans by General Franco’s Nationalists he fled to France where, for a short period, he was interred in a French concentration camp. From there he escaped to England, arriving in the UK on 25 March 1939. His official registration document is shown in fig 1. At first Galí lived in Hampstead. Financially he was supported by the Artists' Refugee Committee, an organisation set up in 1938 to aid victims of fascism, but when their funds ran out in December 1941 he moved briefly to Acton before spending the remainder of his stay in England with family members in Thornton Heath, a village to the southwest of London. Galí soon established himself within the London artistic community and began to exhibit. As early as 1940 when he showed works at the Neighbourhood Gallery, Camden, it was obvious that his style had undergone a sudden and profound change. Previously, as an exponent of Noucentisme, he had painted traditional subjects – landscapes, still-lives and portraits. His compositions were ordered and balanced. Classical influences were strong, although the portraits of women and children sometimes tended towards sentimentality. But, at the Neighbourhood Gallery, we need to look no further than the titles of his watercolours Witch Love; Platonic Love and Romantic Love - to realise that his work had become fundamentally different. Why the new, unexpected, preoccupation with passion in its many varieties? The answer was simple: he had fallen in love. And who was the object of his passion and desire? It was the surrealist artist, Ithell Colquhoun.

fig. 2.

Colquhoun was at that time living in a studio in Fairfax Road, just south of Hampstead (Fig. 3). 1939 had been a momentous year for her: she held a joint exhibition with Roland Penrose, the rich artist who bankrolled the surrealist group in London, published surrealist prose poems in the London Bulletin and travelled to Paris where she visited André Breton and posed for the American photographer, Man Ray. Her future seemed assured, but trouble was brewing. Eduard Mesens, the leader of the surrealist group, wanted to have things all his own way and tried to insist that all group members dedicate themselves to the proletarian cause and cease all non-surrealist activities. But demands for obedience do not sit comfortably within a movement dedicated to the pursuit of freedom and liberty. Colquhoun, who had no interest in politics and who was also a practising occultist, could not accept his conditions. Following a fractious meeting at the Barcelona Restaurant in April 1940, she and several others left the group. Although she retained contact with individual surrealists and remained true to surrealist principles, henceforth Colquhoun described herself as an “independent”.

fig. 3

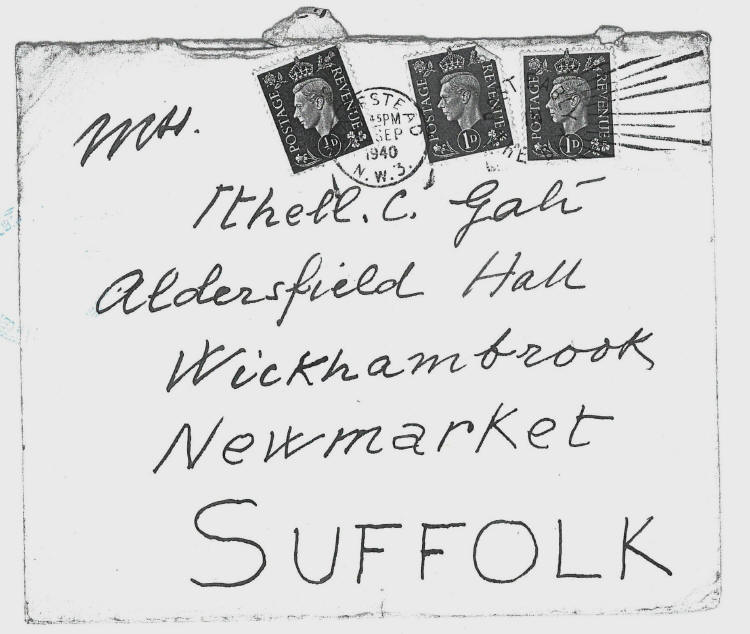

Darling Itta, seagull of the seas The exact date that Colquhoun and Galí met is not known, but it was sometime in the summer of 1940. He was swept off his feet. By August he had begun to write passionate letters to her, exalting her in the hyperbolic language lovers often use: Next to you, Nelson’s column was the height of a twig. You give drops of light from your pearly stomach to the pigeons of Trafalgar Square.[2] His idiom is extravagantly poetic: Last night, I licked the waves of your blood with the tip of my tongue. They stir like scarlet foam on your pearly skin, and I found them salty because you're a daughter of the sea. Galí, - a married sixty-year-old father of eight - was plainly besotted. In one frenzied period when his passion was at its height, he wrote to Colquhoun several times a week, sometimes more than once a day and once in the middle of the night, kept awake by a German bombing raid. In what can only be a form of fantasy wish-fulfilment, he addressed several envelopes to ‘Ithell C. Galí’[3] (Fig 2). He had a key to her studio, stored some of his belongings there and forwarded her post to her when she was away. What drew them together? We can only guess. Unlikely romances frequently blossomed during the blitz[4] but, for both of them, there were complex emotions and motivations. Take Colquhoun: had she fallen for a man or a father-figure? A psychotherapist was convinced it was the latter, suggesting to her that he met an unfilled emotional need. The therapist linked him to the fact that Colquhoun’s parents had been absent in India for much of her childhood and she had been brought up by an elderly spinster aunt. Galí, as a much older man, represented her missing father.[5]

fig. 4.

For Galí, too, Colquhoun may have had a symbolic value. In several letters he recalled that as an eight-year-old he had seen and fallen in love (to the extent that an eight year old can fall in love) with a circus performer, Ida Washington: a young woman ‘perfumed with stars and horses’ manes’ and that, ever since, ‘I have held this sacred memory close to my soul and my senses.’ She became an idolised figure in his imagination, and, for some reason, he came to believe that Colquhoun was a reincarnation of her. Perhaps it was the similarities in their names, Ida/Ithell,[6] or perhaps it was a physical resemblance, but, in his letters he made repeated references to this almost mystical experience. Had he fallen in love with a person, or with a fantasy?

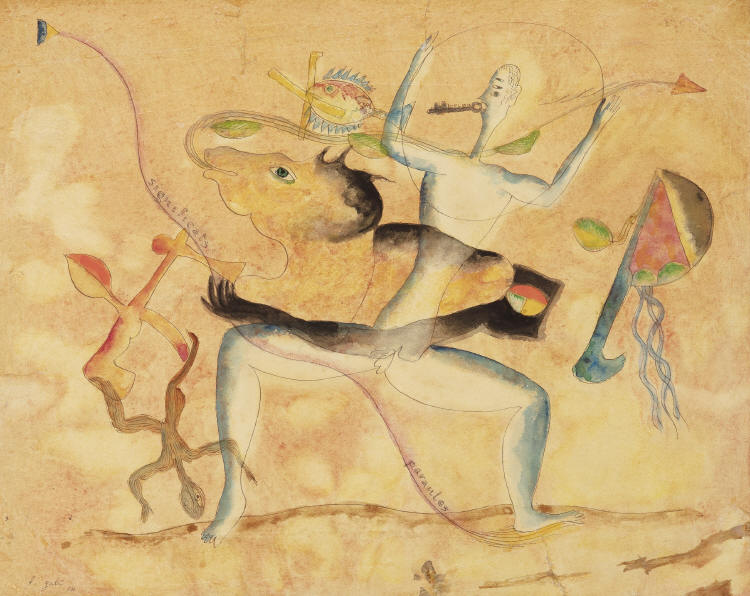

Imagination and Art Aside from its emotional impact on them both, the relationship put Galí in close contact with Colquhoun’s surrealist ideas and granted him an entrée into surrealist circles. Following the disintegration of the surrealist group, surrealist artists were only able to show their work in mixed exhibitions. Many took part in Imaginative Art since the War held at the Leicester Galleries, London, in the spring of 1942. The exhibition was a reminder that, in the midst of war, freedom of the imagination was just as important as civil liberty. Colquhoun showed five paintings and Galí was very well represented by six. Judging by the titles of the works that Galí exhibited (regrettably, none of them can be traced today) Leda; Death and Immortality; Death and Ideal; Still Life: The Five Senses; Stolen Lives and Origin of the Species, imagination, fantasy and mythology were now well-established aspects of his artistic repertoire, a style that continued to be his norm (Fig 4). Colquhoun’s own exhibits showed her developing preoccupation with sex and gender. In The Pine Family (1940) it is seen at its most aggressive. In The Bird or the Egg c. 1940, (once tentatively titled The Search for the Androgyne), her subject is the alchemical conjunction of the two separate genders to form the androgyne, a fusion that she believed was necessary for the spiritual redemption of humankind. By this time she was well into the Diagrams of Love series. But things were not to last.

fig. 5.

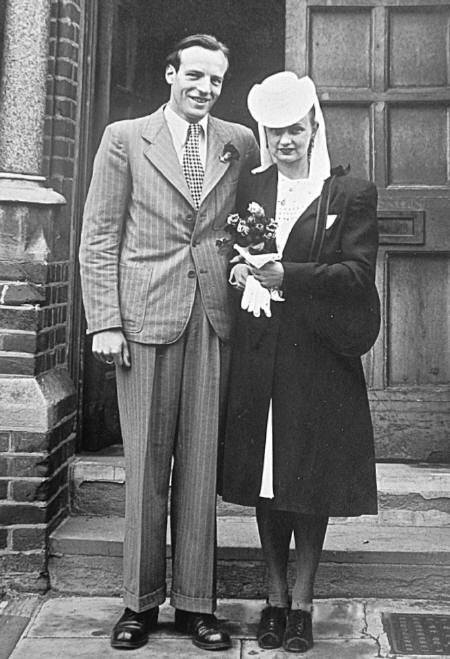

The Arrival of Toni del Renzio Although the letters continued to flow from Galí to Colquhoun, their amorous nature and imagery became much less prominent. When, in early June 1942, he described himself as ‘miserable and desolate’ a low point in their relationship had clearly been reached. The reason for this decline is that she had, in quick succession, met and begun to live with a man whose name and titles were as exotic as his background. Count Antonino Romanov del Renzio dei Rossi di Castellone e Venosa was born in Russia into an aristocratic Romanov family. In the course of a nomadic early life he had been conscripted into Mussolini’s’ cavalry, deserted and travelled to Spain where he fought for the Marxist faction in the streets of Barcelona. Escaping to Paris, immersing himself in contemporary artistic and theatrical circles, before fleeing to England to avoid the rising tide of fascism. Arriving either in late 1938 or early 1939, del Renzio attempted to rejuvenate the ailing surrealist group. His most important act was to edit a surrealist journal, Arson, which appeared in March 1942, the month that he first met Colquhoun, introduced by Mary Wykeham. An inscribed copy of Arson dated 1 April 1942 (Fig. 5) shows that their relationship was still a fairly formal one, but by July he was living with her in her studio, and they married the following July (Fig. 6). It was about this time that the Diagrams of Love series ended.

fig. 6.

For three years Galí did not write at all, but this was not quite the end. That came in January 1946, when he acknowledged that the relationship was finally over. His dream of ‘Idda-Ithell the impossible love’ had ended. Colquhoun’s brief marriage too was nearly over. She and del Renzio separated later in 1946 and divorced the following year. He blamed the breakdown of the marriage on her self-centredness. To the extent that any artist has to be self-absorbed, no doubt she could have said exactly the same about him. By the end of the decade, Colquhoun had largely turned her back on life in London and was spending increasing amounts of time in Cornwall, painting, writing, and devoting herself to esoteric studies. Del Renzio went on to become an influential teacher and writer on art and design, and promoting new movements in British art. As for Galí, family members began to urge him to return to Catalonia. After the war, the political situation in Spain was calmer and they assured him that he would be safe from persecution. Eventually, in 1949, Galí rejoined them. On his return he continued to paint in his new fantasy-based manner until his death. It is one of the persistent criticisms of male surrealist artists and poets that they reduced and diminished their female lovers to the role of muse. It would be a satisfying conclusion if Colquhoun, who knew a thing or two about reversing polarities, cast Galí in the role of her muse for the “Diagrams of Love” explorations. We cannot say for certain, beyond the fact that he was present when she started work on them, and she stopped about the time their relationship ended.

Acknowledgments This article is a much shortened and heavily modified version of a chapter in the exhibition catalogue Francesc d’a. Galí el mestre invisible held at the Museu Nacional d’art de Catalunya, Barcelona, May – September 2025. I benefited from many helpful email exchanges with Dr Albert Mercadé, curator of the exhibition. My thanks are also due to the Galí family for permission to quote from Franscesc’s letters.

[1] Hale, Amy, Sex Magic. Diagrams of Love Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Publishing, London, 2024 [2] Galí’s letters to Colquhoun, mostly written in French, are in the archives at Tate Britain, catalogued as TGA 929/1/707-56. [3] Despite wartime restrictions, Colquhoun’s ability to travel remained remarkable unimpaired. In the years 1940-1 he wrote to her at Cheltenham, Newmarket, Porlock Weir, three separate addresses in Mousehole and once to West Cornwall Hospital where she had been admitted with a broken leg following a cliff-top fall. [4] See Lara Feigel, The Love-charm of Bombs, Bloomsbury, 2013. [5] TGA 929/1/236, dated May 1952. The therapist was Dr. Alice Buck (1908-1999), a Jungian psychotherapist and researcher into extra-sensory perception. Colquhoun was a member of a research group run by Dr. Buck that investigated the possible occurrence of precognition during dreaming sleep. [6] Galí refers to Ithell as Idda or Itta, interchangeably.

Images Figure 1. Galí’s identity card, showing that he arrived in the UK from Perpignan, France, 25 March 1939 and registered on 1 April 1939. Collection: Xavier Galí (Barcelona). Figure 2. Envelope addressed to Ithell C. Galí, dated September 1940. Colquhoun’s reason for visiting Aldersfield Hall is unknown. (Tate Archive) Figure 3. The studio at 45a Fairfax Road where Colquhoun lived and worked between 1939 and 1947 Figure 4. Untitled 1944. A watercolour painting by Francesc d’A. Galí in his new, fantasy-based style. Collection: Xavier Galí (Barcelona). Photo: © Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya/Guillem Fernández-Huerta Figure 5. Front cover of Arson, edited by Toni del Renzio and published in March 1942. The inscription reads “To Ithell Colquhoun. The flames begin to spread on the eve of what even Christians call ‘Passion Week’. Toni del Renzio 1 April ‘42”. (Collection: Gerald Dowden) Figure 6. Ithell Colqhoun and Toni del Renzio on their wedding day, 10th July 1943, outside the Registry Office, Brentford. 6.6.25

|

|

|