|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Accidental art: a note on the graphomanias of Ithell Colquhoun Richard Shillitoe

Visitors to the revelatory Between Worlds retrospective exhibition of the works of Ithell Colquhoun currently being shown at Tate St Ives until 5 May 2025 will see a large number of oil paintings, drawings and watercolours executed using various ‘automatic’ methods of production. These are techniques pioneered in the mid 20th century by surrealist artists in order to bypass reason, conscious decision making and self-censorship in the course of making an image. Instead of controlled brush strokes or pencil movements, the artist makes marks ‘automatically’, apparently at random, or perhaps according to the desires of the unconscious mind. Readers who are familiar with Colquhoun’s esoteric beliefs will not be surprised to learn that she went further than this and claimed that the movements of her hand or pencil could equally well have been influenced by contacts with powers and forces operating from non-material planes. Whatever the explanation for the source of the marks, Colquhoun became a staunch advocate of automatism in 1939 following a trip to France in the summer of that year. Her article The Mantic Stain is the longest and most comprehensive survey of automatic techniques yet published in the English language¹. The automatic techniques that Colquhoun used include decalcomania, fumage and her own invention, parsemage.

Decalcomania Decalcomania is the application of oil paint or gouache to a surface, pressing a sheet of paper against it and then removing it to produce blots and stains which the artist then modifies or interprets. Writing of one of her best-known works, Gorgon (1946) Colquhoun explained that: it is an instance of the method controlling the operator, because I meant to paint a ‘Guardian Angel’ but the result of the automatism was so horrific that I had to call it a Gorgon instead². In other words, the emerging image was in control of what she painted. She simply did as she was told. At the exhibition Gorgon is shown together with its paper ‘peel’, illustrating just how much interpretation Colquhoun has carried out.

Fumage Fumage involves moving a sheet of paper over a smoking candle flame to produce an (apparently) random trail of smoky deposits. For example, The Light of the Magistry c. 1940, included in the retrospective, is a fumage, out of which Colquhoun developed organic forms, including a human torso with a crystal at the centre. The title is a reference to alchemical transformation, suggesting that the crystal is the philosopher’s stone.

Parsemage Parsemage, of which there is one untitled example in the exhibition involves sprinkling powdered charcoal, graphite or chalk on the surface of a bowl of water and lowering a sheet of paper under the surface, thereby collecting a random pattern of particles when it is removed. Visually, parsemages tend to be unremarkable although Colquhoun had high hopes for her technique: I would like to extend my automatism of parsemage through skimming off the dead leaves or other debris from a lake by means of an enormous area of sail cloth passed just under the water surface. Or use aircraft to produce a dance and an evanescent sculpture with the vapour-trails of different colours, or with elongated pennants by day and lights by night³. But alas, her phantasies remained unfulfilled.

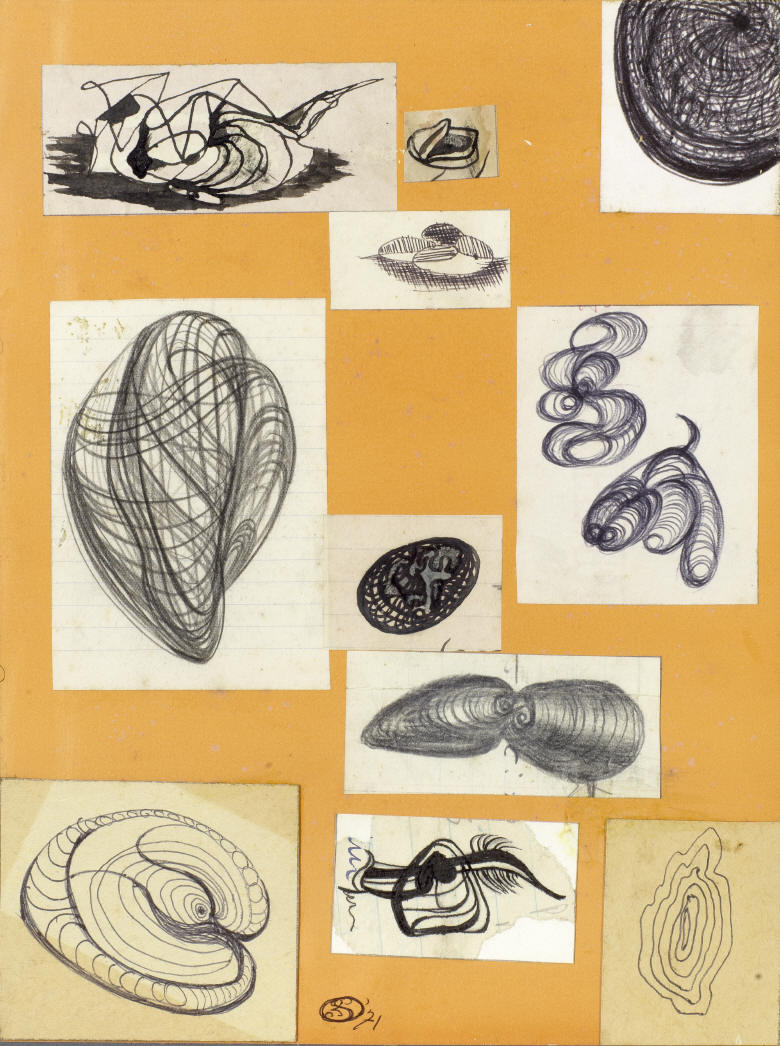

'Graphomania: Black' (1971) Collage of papers laid on card. 10 x 7½in. (25.5 x 19cm.) Photo courtesy Bonhams

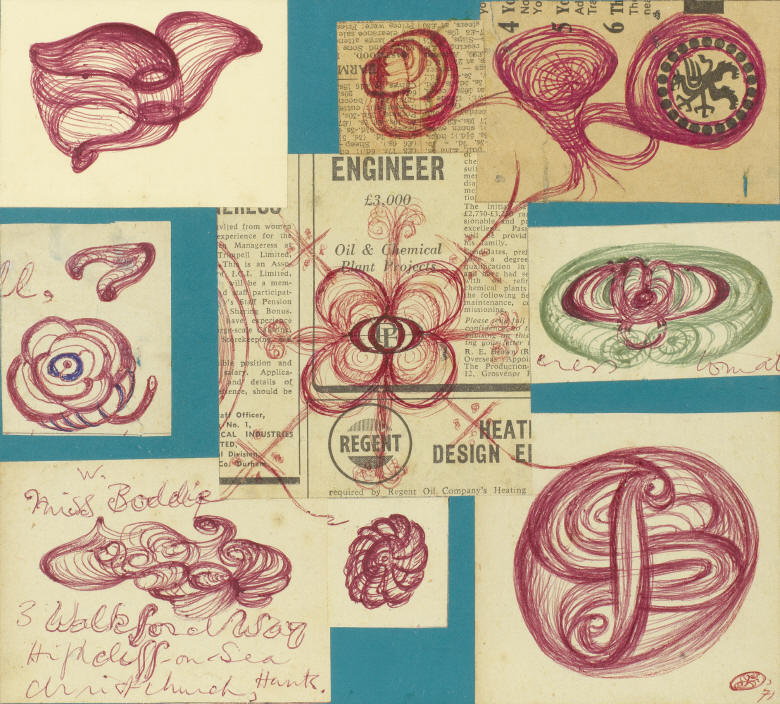

Graphomania There is a technique that can lay claim to being the most automatic technique of all, although the visitor to Between Worlds will look in vain for examples. It is a technique that Colquhoun termed graphomania. Despite the similarly sounding name, it is not to be confused with the altogether different technique of entoptic graphomania, which consists of basing a drawing on marks made by imperfections on a sheet of paper. In all, only eight examples of graphomania are known and only one has been shown in public in the years since she made and briefly exhibited them over fifty years ago. Four are currently being offered for sale in a Bonhams on-line auction⁴. Although Colquhoun’s automatic drawings and paintings are spontaneous, they are also, paradoxically, planned. They are planned in the sense that she deliberately opened her sketchbook or selected her colours with the specific purpose of making a drawing or painting. But there are some drawings that are entirely unplanned. They are the by-product of (or incidental to) another activity, executed to while away the time or to distract her when primarily engaged in doing something else. With no preparation required, in that sense, perhaps they are the most automatic drawings of them all. Colquhoun’s graphomanias are composed of her doodles. They are collages assembled from her doodles, scribbled on newspaper pages among the columns or in the margins. Dashed off in the corners of old envelopes, or scrawled somewhere on sheets of used notepaper or old letters. For most people, they are ephemeral. But not for Colquhoun. Many people doodle, but few carefully cut them out and preserve them as Colquhoun did. Her archives at Tate Britain include an envelope inscribed "Graphomania/collages" which contains, by my count, 57 pieces of irregularly shaped doodles which she has scissored from their source material. Someone even more obsessive than myself may be able to date some of the newspapers, but it is safe to say that the majority date from the 1940s and 50s. With their rhythmic nature, cursive lines and organic forms, many of them bear a close relationship to her automatically produced graphic work of that period. It is likely that, like her drawings, she regarded doodling as a form of automatic activity: images produced from her unconscious mind without active intervention or control and, therefore, worthy of retention. In 1971 Colquhoun was increasingly exploring the use of found materials in her work, largely under the influence of Kurt Schwitters⁵. That year she decided to assemble a selection of her cut outs into a series of eight collages. Making use of her doodles was a way of transmuting ephemeral material into lasting artworks. They were all exhibited at her one-person exhibition in Penzance in July that year. Unusually for Colquhoun, she gave them all simple descriptive titles such as Graphomania: Black (see above) or Graphomania: Red (see below) according to their predominant colour. Despite the bland titles, Michel Remy offers an imaginative interpretation of the collages, seeing them as "attempts to draw circles to go deeper and deeper into the dark, hidden territories of the subconscious, vertiginous, hypnotic spiralling to the centre of telluric forces, where the imagination can feel the energy which brings together man and nature."⁶ But because one’s imagination is such an individual and unpredictable thing, other viewers might find that their journeys into the collages take them to very different destinations.

'Graphomania: Red' (1971) Collage of red biro pen on papers, laid on blue card. 8½ x 9⅛in. (20.6 x 23cm.) Photo courtesy Bonhams

1. “The Mantic Stain”,

Enquiry, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 15-21. 1949 Note: A slightly smaller version of the retrospective exhibition Between Worlds will be shown at Tate Britain, London, between 13 June and 19 October 2025. |

|

|