|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Give us good harvest! Ritual vs The Wicker Man Reflections on the Cornish novel that inspired The Wicker Man by Rupert White

It is hard to read Pinner’s book now without being reminded of this seminal film and, to an extent, of other films of the era like Hammer Horror’s The Witches (1966) or Eye of the Devil (1967) starring Sharon Tate. Certainly Ritual contains a number of familiar folk horror tropes, with The Witches in particular coming to mind because of its rural village setting. Pinner (b1940) was an actor who would have been acquainted with the people who made many of these mid-century horror films. In fact Pinner recalls meeting Christopher Lee in particular, as it was Lee who initially bought the film rights to his book, and first recommended it to Wicker Man screen writer Antony Shaffer and director Robin Hardy. Although Shaffer rewrote Pinner’s story, many elements were retained. In particular Ritual shares with The Wicker Man the same starting premise. A police inspector, David Hanlin, is drawn to a remote village to investigate the possible murder of a young girl, Dian Spark¹. In the process he becomes acquainted with members of the village community, and convinces himself that they are Satan-worshippers. He witnesses children dancing around a giant oak tree and sees suspicious bunches of garlic flowers. He also finds bats’ wings and monkey heads pinned to tree trunks, a church altar missing its crucifix, a Squire who plays weird flute-music, and a vicar given to watering graves at midnight. Outraged, he challenges the Squire: You know as well as I do that garlic flowers are a powerful ingredient of witchcraft… Why was Dian Spark clutching a sprig of garlic? Why did I find garlic on her grave this morning? Why was there garlic on the church altar? Why was there garlic on the giant oak tree, plus two monkey heads and a couple of bat's wings? Why? As readers we, like Hanlin, are drawn into this spooky Satanic otherworld. As the children gather at the oak tree, we hear their leader saying: God is in fire. Not the Christ God! But the Dark God! How many times do I have to tell you tomorrow night we celebrate God! We will dance to give us power over corn and over ourselves!

The most important characters in the novel are retained in the film, though in the book they are less caricatured, and less starkly drawn. Hanlin, whilst concerned about evidence of witchcraft in the village, seems less uptight and puritanical than Sergeant Howie, his Wicker Man equivalent. Similarly, Lawrence Cready, who lives in the manor and becomes Lord Summerisle in the film, is less haughty and aristocratic. The coquettish Anna Spark, sister to Dian, meanwhile, becomes Willow, the Britt Ekland character. Indeed the iconic seduction scene in The Wicker Man, where Willow gyrates up against the wall, knowing that Howie is on the other side of it, is clearly based on an identical scene in the book². Except for the ending, the narrative arc is similar in both book and film. The plot in both cases builds towards a big communal celebration: a pageant seemingly enjoyed by all the villagers. In both cases many of the participants wear animal masks and costumes, and the lord of the manor is dressed as a woman. However in the film, the celebration is a May Day event, whilst in the novel it occurs at night and marks Midsummer’s Eve: …the children (were) cowled in animal skins. Gilly wore a snuffly beaver’s mask and paws. Susan and Joan were March Hares in June. The twins wore lizard’s heads. They throbbed like human drums onto the dead street. Slowly, slowly, with the moon silver on their black hoods the grown-ups followed. They all carried torches. Significantly, in the book there is no wicker man, and instead of a human being, the sacrifice is of a white horse that is killed with two ceremonial swords. The ritual, which is presumably that referred to in the title, is presided over by Mrs Spark, the ‘witch’, who intones: For centuries we have done this. Given you and the sea your rites. Give us good harvest and good darkness. Give us’… Hanlin struggles to come to terms with events - and particularly the sexual abandon that ensues after the horse sacrifice - and so he suffers from the same mixture of disgust, frustration and paranoia as Sergeant Howie in The Wicker Man. We are aware that at times he questions his sanity and, as the novel proceeds, he becomes increasingly desperate. This descent into madness is strongly emphasised in the book, and in fact provides the basis for its abrupt and somewhat unsatisfactory ending. It would

be wrong to reveal this ending, suffice to say that it is clear why it

needed rewriting by Shaffer. This is mainly because in Ritual the

Midsummer’s Eve celebrations, and indeed all the pagan and witchcraft

elements, end up being incidental to the story not integral to it, as

they are in The Wicker Man. In Ritual they turn out to be a smoke

screen, or a distraction, in that they do not explain or justify the

four murders that occur. In fact in the book, the ‘twist’ ends up being

so tame that it suggests that the author, ultimately, lost his nerve.

Certainly the book’s ending doesn’t involve the policeman being

sacrificed at sunset on the cliffs, which of course is the true

stand-out, jaw-dropping moment in the film. In addition, perhaps because of the importance of this final scene, the film makers were careful to base The Wicker Man on recognised pagan precedents, with the wicker man itself described originally by Romans like Julius Caesar, and other elements taken from recorded folklore, and in particular Frazer’s Golden Bough. This added authenticity gives the film both depth, and moral complexity. Sadly the pagan elements in Ritual seem half-baked, unconvincing and poorly researched by comparison. The other big point of difference is the setting. Whereas The Wicker Man is set on a Scottish island, Ritual is set in Thorn, a village in Cornwall, which we learn is near Tintagel. Thorn is close to the sea, which Pinner, typically, describes as follows: Although the final blood of sunset is two hours in the future already the sky is a glass of honey. A fringe of cloud haunts the skyline of the sea. And the sea is searching out the secrets of the shells on the wet beaches…a seagull with oil on his fingers skids a wedding spray in the foam. Then he furrows his left wing between the breasts of two waves and coils for the land… Or again, as Hanlin is walking on the beach: The sea was a roar of green crystal. The sun licked the sea. Shells cracked under his feet. It was good. Although the Midsummer celebrations take place on this same beach, the depiction of Cornwall is not hugely convincing. None of the characters or places have typically Cornish names³, and little effort was made to incorporate any authentic Cornish folklore or witchcraft. Unfortunately it seems Cornwall was chosen as the nominal location for Ritual simply because of its remoteness from London, and in fact the implication in both the film and the book is, of course, that only in remote rural villages would pagan practices like those described survive, or emerge⁴. Lastly its interesting to note that Pinner’s character Lawrence Cready who lives in the Manor, owns a private Witchcraft Museum. This in turn suggests that David Pinner may have visited the museum in Boscastle at around the time he wrote the book, though his description of Cready’s museum sounds more Dennis Wheatley than Cecil Williamson: There were purple shelves on the walls filled with purple books. The sign of the Zodiac and the Pentacle were balanced either side of the window. A black velvet covered table was placed directly in front of the window suggesting a portable altar. On top of it, jet candles reared their horns to salute Cready’s moustaches. Two swords with giant silver swastikas were placed next to the candles. Pinner’s purple-hued prose style has been criticised by some, and so too his casual sexism, but I would argue he has a lively, passionate way of writing that is all his own. Overall, then, though Ritual is flawed in its structure and detail, it remains a fascinating and entertaining read, particularly if you are a fan of The Wicker Man. Just be prepared for a hugely underwhelming last chapter.

1 In fact, unlike the film, in Pinner’s book the death of the girl is quite explicit, as it forms the opening scene of the book. She is described falling from a giant oak tree. 2 Some characters in Pinners novel don’t have Wicker Man equivalents, however, especially Mrs Spark, who is regarded as the village witch, and conducts a séance, involving a butterfly, early in the story, and later hypnotises Gilly, who is one of the suspects. 3 In fact Thorne, spelt with an ‘e’, is an in-land hamlet in North Cornwall, and the name of a manor in the Domesday book, but the name seems more Anglo-Saxon, or Anglo-Norman, than Celtic in origin. 4 This phenomenon of ‘pagan survivals’ is helpfully explored in Ronald Hutton’s ‘Queens of the Wild’ (2022). |

|

|

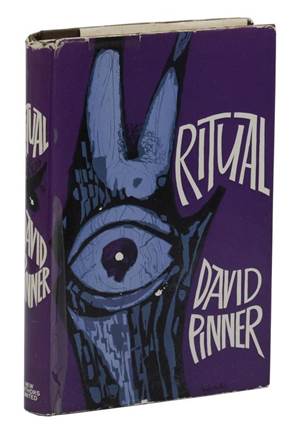

Ritual,

a novel by David Pinner, first came out in 1967. It sold poorly at the

time but it was republished in 2011 after a growing number of folk

horror fans became aware of its influence on The Wicker Man of 1973.

Ritual,

a novel by David Pinner, first came out in 1967. It sold poorly at the

time but it was republished in 2011 after a growing number of folk

horror fans became aware of its influence on The Wicker Man of 1973.

Hanlin,

likewise, challenges the children: It was bad what you were doing

wasn’t it? You were praying to the oak, weren’t you? You were

worshipping the tree where your friend was murdered, weren’t you?

Hanlin,

likewise, challenges the children: It was bad what you were doing

wasn’t it? You were praying to the oak, weren’t you? You were

worshipping the tree where your friend was murdered, weren’t you?