|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Tony Shiels 1938–2024 The last man standing from the definitive 1958 -1963 period of St Ives art who took the abstract landscape genre forward to exuberant modernist figures and myths. Steve Cousins

The late Sir Alan Bowness, once the Director of the Tate gallery, who had praised Tony’s paintings in the early 1960’s and indeed owned one, said tellingly before Tony’s 2016 retrospective at the St Ives Belgrave Gallery: “Tony has lived the artist’s life”. I can think of no better epitaph than that to sum up the excitement, struggle and ultimate satisfaction that has come from him being true to his lifelong artistic adventure. Although born in Salford, he was brought up in the salty coastal towns bordering the Irish sea culminating in Lytham St Annes on the Lancashire coast. Here his exposure to modern art was limited to a small Penguin - or rather Pelican - book by Herbert Read. In 1951, when he was 13, his parents brought him to the Festival of Britain in London where for the first time he saw original works by Picasso, Matisse, Miro and Ernst. Step forward to 16, and Shiels was asking to be allowed to go to London and study at Heatherley's Art School for two years and immerse himself in what the Modernists had to offer. The excitement continued at age 18 with a period of study at the Andre Lhote Academie in Paris where instruction was given by Lhote as a respected artist with true Cubist roots. Then on to Cannes, Nice and Antibes where he immersed himself in the Picassos at the Grimaldi Palace. We can perhaps judge Shiels’ confidence in that he went to visit Picasso, who was either out or did not open the door to him! Andalusia in Spain was his next point of call where he spent time developing an automatic and continuous drawing technique which he declared to be a fusion of rheology (study of flows) and eroticism. He called this style 'Rheotism'. These works were quite beautiful but seemed to shock leading to some national notoriety at the time in the Daily Mirror and Daily Sketch.

In 1958 he arrived in Carbis Bay with his wife Christine and young son Gareth and stayed in the St Ives area until 1963. This period was the high point of St Ives modernism and the young but artistically experienced Shiels mixed with all the main players there as an interesting mover. When the late Frank Ruhrmund wrote of Shiels it was always as a member of the 'Gurnards Head Gang', the wild drinking and notorious group of artists comprising Bryan Wynter, Roger Hilton, Terry Frost and poet W.S.Graham. The latter famously wrote a prose poem for Tony, 'Your drawings shoot my walls', with the first line: 'Please take off your doc top hat and let me say your drawings seem to shoot my walls to pieces'. And worth the ending too: 'He was a tall lean man with a face that you would look twice at and the second time look away and take care to keep your hand from your gun. His name was Rank Shiels.' Yep, Tony Shiels could feel a bit dangerous even though he was in reality more of a charming, well-read intellectual who was just acting out the dangerous part. Although he did drink a lot. Tony had a huge visual imagination. He came to St Ives aged 20 with several styles under his belt from his brush with European modernism but was keen to experiment and learn from the prevailing styles of the major local artists. Peter Lanyon literally lived up the road in Carbis Bay and came to visit Tony saying, ‘I hear a new artist has moved in the area’. Lanyon was certainly an initial influence on him. But Tony soon developed his own landscapes, and then night landscapes and landscapes with semi-hidden figures. His first commercial success came from

abstract seascapes in turbulent milky blue gouaches. This enabled him to

begin to carve out a special, but to this day not really acknowledged,

gap in the St Ives canon. The St Ives location is really about the sea

in all its glory and brutality. Let’s not forget that local seafarer

Alfred Wallis went to sea as a cabin boy aged 9 on the Newfoundland run.

Yet with the exception of Lanyon, the major artists in St Ives were

‘land-lubbers’ from metropolitan England or

middle Europe and were intent on local landscapes or quaint harbours

rather than dangerous seascapes. Shiels and his upbringing around the

Irish sea brought a different heritage.

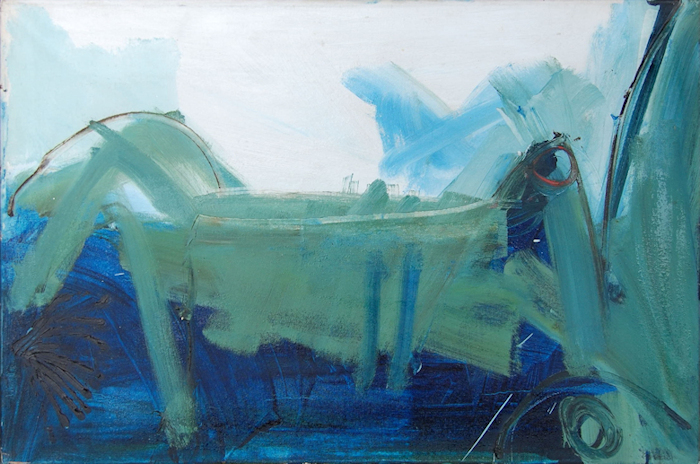

Torso

1961, St Ives

This group of Shiels'

works now feel much truer to the hormonally charged youth culture of the

time and may yet get the recognition that they deserve from Tate St

Ives.

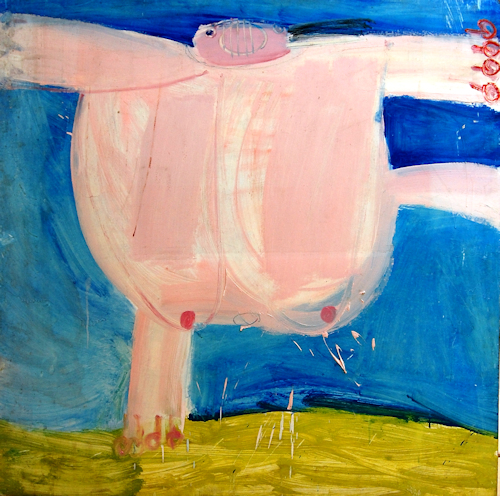

Shy Spectator (1963)

In 1975 he conjured up and photographed ‘monsters’ in Falmouth Bay and Loch Ness. In the Ben MacGregor award-winning film of Tony's life, the then Tate curator Chris Stephens points out how art now includes some very diverse practices. Stephens says that if you wrap up Tony’s painting with the Punch and Judy material, or the Celtic myth of the giant sea monster, you can see it all as much more of an artistic whole rather than as one career as a painter distracting from the other. Throughout this period through to the 1990s Shiels also continued to paint, but these were smaller works on paper rather than on canvas. Nonetheless he continued to exhibit in mixed shows in galleries across the UK. A major retrospective was held at the Salthouse Gallery in St Ives in 1991 with nearly all the early work bought by the Austin Desmond gallery which was the main London gallery for modern British Art. The move to Corofin in County Clare in Ireland in 1993 led eventually to some financial stability with an artist's pension allowing a return to producing larger works on canvas. Tony's cottage was very close to the Burren, and although many miles inland he was thrilled that it was made from the bodies of sea creatures, and a large Burren Sea head was made.

From Corofin Christine and

Tony moved to County Kerry near Killarney where they lived out their

lives together in modest comfort. Art-wise,

several solo exhibitions followed, mainly in

Cornwall though with a show in the Salle

Giacometti at the Maison de Culture in Amiens in 1997. Further

exhibitions followed in Brittany which chimed with Tony’s Celtic

instincts. There were also shows in the UK at the Belgrave in St Ives

and several at Paul Longthorne’s gallery in Marazion. The three solo

shows, at Daisy Laing Gallery in Penzance, including

'Tony Shiels at 80',

were his last selling exhibitions and proof of his late life vitality in

Making Marks.

The second exhibition was to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the Penwith Society of Arts. Tony turned out to be the only artist in the show still alive and at last he shared the gallery walls on an equal basis with Peter Lanyon, Dennis Mitchell and the other ‘greats’ of the period. The show included Shiels’ first major Sea head 1960 and a large work, painted just after the Cuban missile crisis, of pink nudes falling as bombs onto a beach titled Four Frightened Bathers 1963. The St Ives group and Penwith Society is seen by scholars as a result of artists either avoiding WWII or recovering from it. Shiels as a post-war sixties youth reminds us that risk of war has not gone away for ever, and like the climate risk, this nuclear risk is as present as ever. Just “Making Some Marks” and proving that “I was here” in the world, “I was here”, he says, sagely. We thank him.

Steven Cousins is author of Tony Shiels: Third Generation St Ives.

|

|

|