|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Daniel Sturgis on Abstract art and The Indiscipline of Painting

Painter and curator

Daniel Sturgis discusses the 2011 Tate St Ives Winter exhibition with

Rupert White

Is this show most easily

thought of as providing an alternative

history of post-war abstract art?

One

of the big problems for painting is the idea of history. That is the

biggest burden painting has, because now if you're an artist you know

that history has already been written. It's too late. That history was

written by eminent critics in the last

century, and artists themselves who said they'd taken painting to an

endpoint. This

exhibition is about thinking:

well if we can't contest those writings,

where does that leave us?

What can we do, and continue to make

work that still has an element of

criticality? One

of the big problems for painting is the idea of history. That is the

biggest burden painting has, because now if you're an artist you know

that history has already been written. It's too late. That history was

written by eminent critics in the last

century, and artists themselves who said they'd taken painting to an

endpoint. This

exhibition is about thinking:

well if we can't contest those writings,

where does that leave us?

What can we do, and continue to make

work that still has an element of

criticality?

Artists as curators seem good at searching out less familiar works,

and finding the unexpected...

Curating exhibitions and thinking about how

works relate together is fascinating.

It's what one does

as an artist. Particularly

within painting you're drawn to thinking

about other paintings and

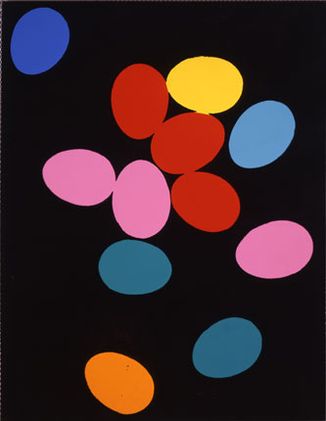

searching out the incongruous work - like for example the

Warhol egg paintings

(picture right). Also I'm drawn to artists

who themselves had had great doubt about what they're

doing - so there is an uncertainty,

a provisionality, within the

paintings themselves.

Many such works tend to lie outside existing

narratives or theories.

Artists are naturally

sceptical about theory anyway...

You're right to be sceptical of everything really. But history is part

of what one inherits and needs to do something with - and either

ignore or use. By their nature many of these works address the history

of modernism because the language of abstraction

is so tied to it. Some seem very postmodern,

some are more happy in the modernist guise, in their modernist

skin.

The term abstract derives from the idea of abstracting forms from

nature - as maybe Cezanne might have done. It's

a term that's lingered on but now abstract art is actually

representational in the sense that it tends

to represent other paintings.

There's no doubt that people making paintings that look abstract now

are doing it for very different reasons than they were 100 years ago.

This exhibition shows the close relationship - a shared language -

that formalist painting also has with

design. So Alex Hubbard uses a design from Memphis design group within

it, and the Tim Head painting has a pattern from the inside of an

envelope. They're representational in that

sense too.

There's

a strong French/Swiss presence in the show. There's

a strong French/Swiss presence in the show.

There are various groupings like that that you can pick out. As well

as the modernist history, Clement Greenberg and the others, there are

the challenges to that history. One group of artists

- Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset,

Niele Toroni

- worked collectively in the 60's

and coauthored works. They're

all represented. Their legacy is also evident in people like John

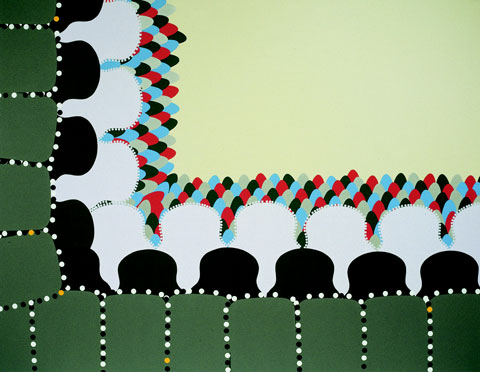

Armleder (picture left), and Francis

Baudevin.

In a sense they represent a

continental European challenge to that

very familiar American modernist art

Yes. A number of the American painters, like

Peter Young - an older artist

- or David Reed

showed in Europe first, in Germany.

That's important. And the

Conrad Fischer Gallery is

important, which had early exhibitions

by people like Carl Andre and Bob Law and Richter and Palermo.

Bob Law is the artist with the strongest connection to

the St Ives 'school'.

Talking of which, there was a strong

landscape influence in the work that was made here.

It's not really evident in many of

the paintings in this show - but your own work has some

interesting landscape references...

I have made work that touches on landscape, and has a connection not

only with design and schematic landscapes

but with a history of abstract painting. And

in a British context that certainly

came out of landscape painting. But it's

far removed.

The distance creates an

interesting tension in your work, because its not what you expect, or

see straight away.

I like to use the word doubt. You're not

sure whether you're meant to be reading it

that way. That little element of doubt or uncertainty.

You teach in the art schools in London. Are many students making abstract paintings?

There are hundreds of people making

wonderful paintings.

I think that the important thing within any art

form is the question of what is at stake: about

the criticality in what one is doing. I think one sees that in

different connections within a show like

this. I think, from teaching at Goldsmiths

or Camberwell or the RA,

that there are people who are interested in

it, but it's not for everyone.

Can you explain the term 'criticality' a bit more?

I think it's about whether a painting

is more than just a decorative object. Can it be more than just that

or is that enough to be aiming for?

It's about the way ideas are held within an

object. Painting is the most conceptual art form because it asks you

to think about questions of value, of decoration,

of the market, of its status as a commodity: all these things are tied

within it.

Doesn't that

apply to all painting?

Yes, but within abstract painting it is enhanced, because there are

these histories that are tied within it. But we

should remember: they also give pleasure. And I like the

perversity of that.

See 'exhibitions' for installation shots of The Indiscipline of Painting exhibition 9/10/11 |

|

|