|

Jonathan Paul Cook on Footsbarn, communal

living, and rural theatre

Footsbarn Theatre formed originally in Cornwall in 1971,

where they made their name as a pioneering theatre group before moving,

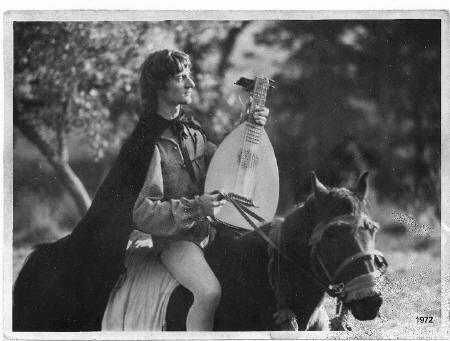

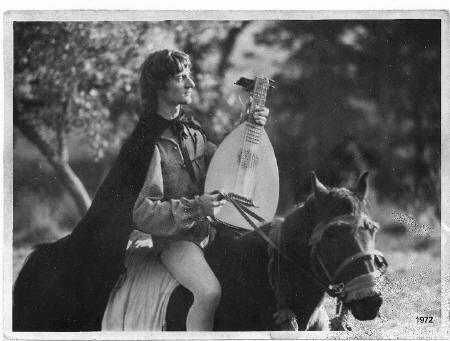

ten years later, to continental Europe where they are based now. JP Cook (picture

below right as 'Tristan') was their co-founder. e-interview by Rupert

White

Can you say a few words about your early life? Where did you live as

a boy? How did you first become interested in acting?

One could say I first wore a mask even before I was born! My mother

danced well into her pregnancy in Ballet Jooss' post-war tour of Kurt

Jooss' famous masked ballet ‘The Green Table.’ She used to tell me

‘You've danced on the best stages in Europe!’ It was her colleagues who

educated Pina Bausch. After I left Footsbarn she took over my role as

the movement trainer, and also choreographed some of their dances. When

Footsbarn was in rehearsal in far away places like Portugal and Italy,

they used to fly her out from Cornwall to work with them. ‘Someone has

to get them up in the morning!’ she used to say. She taught a weekly

dance class in Lostwithiel well into her nineties.

My father was a musician. He conducted at the Old Vic for Olivier, and

composed for Tyrone Guthrie and Michael Langham at the Stratford

Shakespearean Festival, Ontario, Canada.

My first memories of life and theatre are of Stratford-upon-Avon,

England. When I was seven we emigrated to Canada where I began to act on

stage and television, pro and semi-pro. I also built a theatre in the

family garage, and, in the cellar, a grotesque horror-house installation

to terrify my playmates. On one occasion my best friend and I covered

ourselves with ketchup and fought to the death in the open street,

causing elderly neighbours much worry. Aaagh, Melodrama!

When I was fifteen we moved to Boston, USA. As a teenager I was a

science nerd, although I found the students in the highschool Drama and

Folk Music Clubs to be much more fun than my fellow nerds!

You co-founded Footsbarn theatre group, based at Trewen near

Liskeard, with Oliver Foot in 1971. Can you explain where you originally

got the idea from? You co-founded Footsbarn theatre group, based at Trewen near

Liskeard, with Oliver Foot in 1971. Can you explain where you originally

got the idea from?

The idea of a barn originated at Goddard College in the mountains of

Vermont (north of New York), where Oliver and I first met. There is a

theatre there called the 'Haybarn', where we acted together in

productions of 'Twelfth Night' and 'A Taste of Honey'.

We were both familiar with the Barn Theatre at Dartington, both having

family from the Westcountry: that we found another Englishman with

shared references and interests, seemed like an extraordinary

coincidence. So we began dreaming and planning about getting our own

barn theatre in the South West. We had a book, 'The Book' as it was

accurately and affectionately known, in which we wrote and passed back

and forth our latest ideas about our big dream.

When Oliver and I were not jamming on creating a theatre company in the

Westcountry, we were impatiently waiting for the next Beatles album to

arrive, and wondering how it would alter the Universe, and point to the

next step in human evolution!

What was Goddard like then?

Goddard was an exceptional theatre environment. There was an emphasis on

devising, and there was already performance art being presented. Bread

and Puppet Theatre performed twice while we were there, before and after

their success at the Nancy Festival, and eventually became the resident

company.

When I first arrived there, it was in the hope of studying the

psychobiology of perception (Yes, really!), but a fellow student by the

name of David Mamet (now a well-known screenwriter) suggested I investigate my childhood interest in

theatre. ‘Okay,’ I thought, ‘Just one non-academic pursuit.’ One class

with Pablo Vela (of Meredith Monk's ‘The House’ fame) and for the first

time I realised it wasn't just with science that one could experiment.

And it was mainly that, the experimentation, which I loved. I was

hooked!

Fellow Goddard student Jeff Glaser, David and I formed a little

travelling company, ‘Suitcase Theatre,’ and toured New England colleges

and Montreal in 1967. Some years later, but still an unknown writer,

David offered me ‘Duck Variations’ to take back to Footsbarn. ‘Yes,’ I

thought, ‘But no, not really Cornish fare,’ and politely declined.

Idiot! To think how close Footsbarn came to presenting the first

European production of a Mamet play!

After opting to specialise in drama you and Oliver attended

separate drama schools…

Yes, we took off to London and Paris, quite consciously to equip

ourselves for forming a company.

You trained with Jacques Lecoq in France. Can you describe his

teaching? How did he inspire or affect Footsbarn?

Lecoq's work followed from his belief that theatre needed to return to

its roots to revalidate itself. He did not posit any ideal aesthetic. So

his teaching was very much in sympathy with our eventual research into

an ‘untouched’ audience.

Lecoq’s application of the ‘via negativa’ kept his students in a state

of almost constant frustration, but the process selected for passionate,

resilient artists. His approach to the body was all about understanding

and exploiting what was there, rather than imposing perfect forms upon

it. He saw mime as only a starting point, not a finished genre. He

looked to the rhythms of Nature to challenge the student actor's powers

of transformation.

Lecoq introduced us to a spread of traditional, evolved theatre styles

such as the commedia dell' arte and clowning that served us well as

tools to explore our relationship with the Cornish audiences. And of

course there was all the mask work, which chimed with the earlier Bread

and Puppet influence. Eventually, when the company became established in

France, he was very supportive and even gave the actors free workshops!

And then you and Oliver regrouped?

Yes, after two years training, bringing other actors with us. Arriving

back in England, I presented Oliver with a wooden mug, saying ‘This is

the kind of theatre I want to do.’ It was hand carved out of a single

block of wood by an East European craftsman. The handle projected at an

odd but accommodating angle, and the rough surface was stained a deep

maroon from two years of drinking French wine and Normandy cider.

Oliver had met a group of musicians in London and one of them, Tom Wildy,

later a Plymouth Councillor, had inherited some money from his

grandparents which became our front money for buying the Trewen

property.

Contrary to information one might find on the internet, the Foot family

never owned the barn at Trewen. Tom and Oliver became co-owners with the

understanding that Oliver and the theatre company became responsible for

the mortgage payments and community expenses - a rather bizarre and not

entirely successful arrangement! Oliver was the nominal theatre director

for the first year-and-a-half, and it was hoped that the family name

might open up some doors for us.

Who else was involved in the first year or two of Footsbarn’s

existence? How did you know them, and what was their contribution?

There were five original members of the theatre group: Oliver, myself,

Serena Hendersen whom I brought with me from Lecoq, and Maggie Watkiss

and Andrew Slimon who were Oliver’s fellow students at Peter Layton’s

Drama Studio in London.

Serena was an actress with a broad range, a charged imagination and a

convincing vulnerability. Maggie would tackle any role with warm

generosity and a light comic touch. She was for many years a stalwart of

Footsbarn. Both women were devoid of ‘actressy’ posing and vanity. Andy

was a wiry, passionate actor and a great on-stage partner, naturally

demonstrating the ‘complicity’ that Lecoq valued so much.

A couple of the musicians (Tom Wildy and Richard Worthy) were also

talented actors who had trained at the East 15 theatre school and

participated in some of the productions, but like almost every young

actor I have met, their dreams were to be rock stars!

Very soon after we started, Dave Johnston, one of Oliver’s old friends

from Dartington, came by with his guitar on his shoulder. A talented

song writer with a theatre background, he was on his way to being the

next Donovan or Cat Stevens, but became sidetracked by our ambitious

little project. As a writer, Dave was to become the single most important creative

influence within the company for many years. He combined musicality, a

raw sense of language, and a sense of story.

Quite early on, Keith Bruce, an inventive designer and friend of Andy

Slimon, came down to Cornwall to be our set designer and mask maker.

Michael Novotny, an American friend from Goddard College dropped by on

his way to Africa and also wound up staying. Mike was a talented

painter, and knew a lot about printing and glass fibre construction.

Keith and Mike took over the Trewen garage, hung up a sign that read

‘Stallion Enterprises’ and went about developing a visual language that

was part underground comics, part Francis Bacon, and part Fairground

kitsch.

They were supplemented in the costume department by my sister Jenny who

had studied fashion design and would later be Costume Supervisor at the

Royal Court Theatre.

Siblings working together were not uncommon at Footsbarn. Dave Johnston

brought in his brother Steve to work as musician and actor. Paddy Hayter

brought in his brother Dave to work as a technician.

New actors weren’t hired or even vetted in any conventional way. They

more or less just ‘happened.’

Joe Cunningham came down to be a roadie for the musicians, participated

in the movement training, demonstrated a flair for physical

characterization, was given a drum to bang in ‘Tristan,’ and before you

could say ‘Nice one Cyril!’ had begun his life’s career as a Footsbarn

actor.

Steve Lawrence had been an eager student at a weekly workshop Oliver and

I taught at Plymouth Arts Centre. As soon as he was old enough he came

out and joined us as an actor and eventually also took on administrative

responsibilities.

Joanna Tagney dropped by to investigate rumours of Cornish creative

madness and ended up staying for some years.

I had known Margarete Biereye at the Lecoq school. By coincidence she

later hitched up with a lad from North Devon, Paddy Hayter. Paddy had

visited us and expressed an interest in Footsbarn before he left for his

two year training with Lecoq, where they met. When they had finished

their training they came to join us.

Eventually Paddy would be the one to fight the hardest and longest to

keep Footsbarn on the road.

Can you describe what life was like behind the scenes at Footsbarn at

that time? I understand it was quite a large community: the barn itself

being used for rehearsals, and many of the actors living in caravans

etc. nearby.

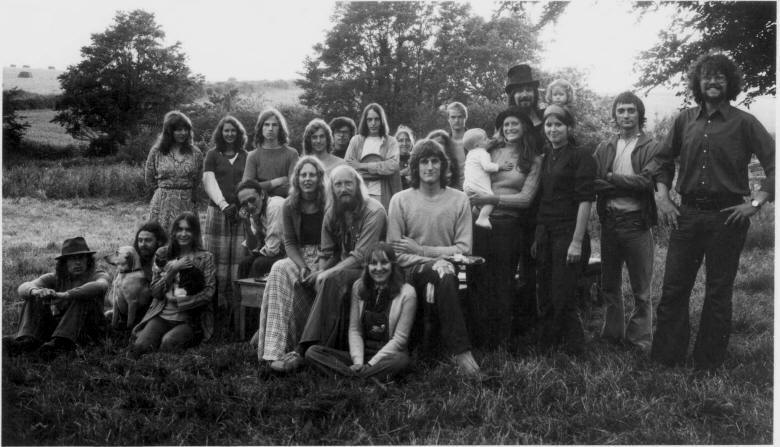

Yes, Footsbarn was as much an anthropological as an artistic phenomenon!

It was part of the larger entity 'Trewen Community,' Trewen being the

name of the farm that straddled a lane between Liskeard and Looe. With

families and all, there were between fifteen and thirty people living

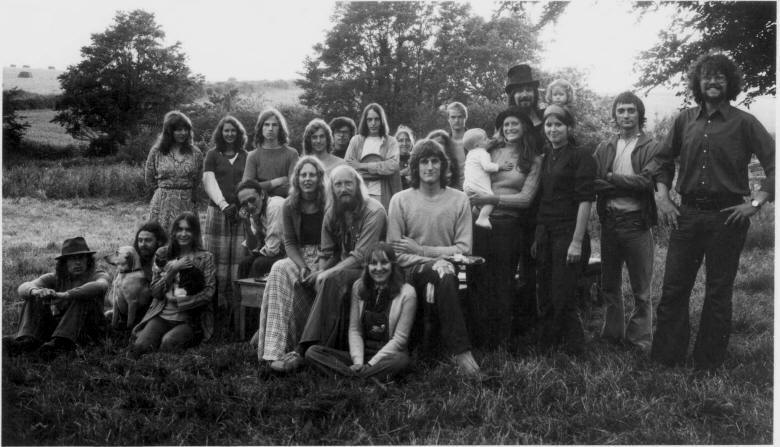

there (picture above: the Trewen Community in early 1972). We worked in the barn, and there were also stables that became

the studio for the musicians.

For public consumption it was always: 'No we are not a commune, we are a

community!' But in fact I have yet to come across a more chaotic and

intense form of communal living. Perhaps it was precisely because there

was no considered social ideology behind it, that it was able to be so

extreme and yet endure. In the beginning there were a minority of

idealists for whom a structured alternative way of living was of

particular importance, but they gave up in despair and left after but a

year or two.

There were no personal wages, just endless brown rice and beans.

Everything was bought in bulk, even the toothpaste. I remember a five

gallon drum of yeast extract sitting in the pantry that lasted four

years; just scrape the mould off the top and dig in. There were sporadic

attempts at tending a kitchen garden and raising goats, but the only

real success was with Jerusalem artichokes, a plant that really knows

how to fend for itself. And of course there was a well publicised

temporary success at growing a certain non-edible crop, but that is

another story.... There were no personal wages, just endless brown rice and beans.

Everything was bought in bulk, even the toothpaste. I remember a five

gallon drum of yeast extract sitting in the pantry that lasted four

years; just scrape the mould off the top and dig in. There were sporadic

attempts at tending a kitchen garden and raising goats, but the only

real success was with Jerusalem artichokes, a plant that really knows

how to fend for itself. And of course there was a well publicised

temporary success at growing a certain non-edible crop, but that is

another story....

Sometimes a new member of the community was designated as cook – one

could hardly say hired – and there would be a meal waiting for us on the

Aga when we came back in the evening after a performance. Otherwise it

was the ubiquitous 'cheese dream' - melted cheese on toast – or peanut

butter spread on unleavened bread baked in bricks so hard it needed an

angle grinder to slice them.

After a couple of years a concession was made to individual needs. In

the kitchen, high up on a shelf, so high that you needed to stand up on

a chair to reach it, was a jam jar in which ten or fifteen pounds

sterling would be placed weekly. You could take from it at your own

discretion, but presumably the inaccessibility gave you plenty of time

to struggle with your conscience.

Commune or community? Well for the most part we didn’t care. We were

much too involved in making theatre and music. We avoided holding

community meetings whenever possible, and it was not unusual to hear

someone shouting across the fields 'Community? Fuck!!' We were

shamefully delinquent in caring for the beautiful Trewen property.

Attempts at overt leadership were met with suspicion and derision.

But it was this same anarchic tendency to question authority and shun

the conventional that nudged us towards devising our own material, and

kept us stubbornly looking for an original Cornish style even as the

well-meaning Ian Watson, Director of South West Arts, understandably

implored us to straighten up our act and bring in an outside director

for a few months to help us out.

Footsbarn was prolific during your time with them. Can you list the

productions that you remember? Is there one that is particularly

memorable, or notable?

Here’s a list of the shows produced while I was there. I won’t vouch for

all the dates. The venues ranged from well established institutions such

as Dartington Hall, Plymouth Arts Centre and the Falmouth Arts Centre (FAC),

to village halls, town squares, beaches, pubs, working man’s clubs and

schools. We never performed for the public in our barn. It was only used

for rehearsal. We usually opened our winter touring productions at

nearby Trewidland Village Hall, for the simple reason that if we had

forgotten something, it wasn’t far to go back and get it.

From established writers:

'Endgame' Beckett, 1971 (DH); 'The Bald Prima Donna' Ionesco, 1971

(PAC); 'The Bear' Chekhov, 1972 (FAC); 'A Resounding Tinkle' NF Simpson,

1972 (FAC); 'Zoo Story' Edward Albee, 1972 (FAC); ‘Next Time I'll Sing

To You’ James Saunders, 1972 (FAC).

Written, devised or heavily adapted by us:

'The Gump St Just' 1971; (Piran Round);

'Tregeagle' 1971 (Piran Round); 'Perran Cherrybeam' 1971 (various

locations); ‘Jeux Gratuit’ 1971(DH); 'Woodcut' 1971 (PAC); 'Giant' May

1972 (tour and FAC); 'Crow 10' 1972 (FAC); 'Tristan' 1972 (village

halls); 'Master Patalan' May 1973 (outdoors tour); 'Jack and The

Beanstalk' Winter 73/74 (village halls); 'Pot of Gold' May 1974

(outdoors tour) 'John Tom' 1974 (village halls); ‘Underwater Worlds'

1974 (Theatre In Education school tour); ‘The Scarecrow and The Corn

Spirit' and 'Greta’s Follies' (children’s shows); ‘Incident at Crazy

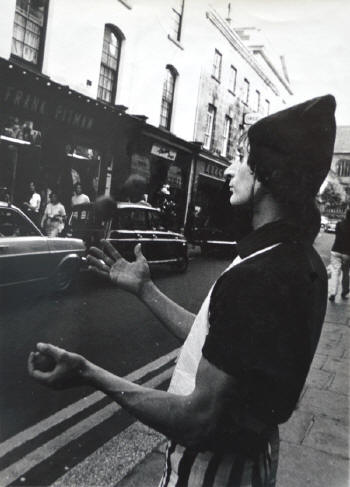

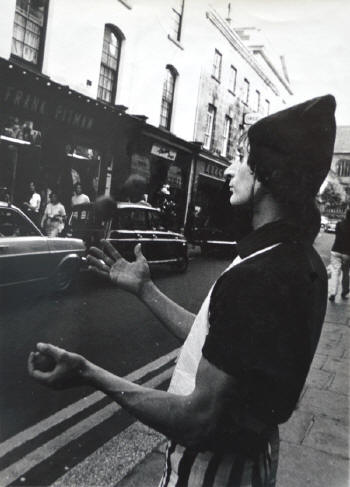

Cowpoke Saloon’ (pub show - picture above); 'Legend' May 1975 (first tour to use the

marquee).

'Tregeagle' was a moral tale about an evil judge. Played at Piran Round

(picture below),

an ancient earthen works fortification the size of a field. It was site

specific, as one would say now. We were spread pretty thinly in that

large space, for which we endeavoured to compensate by inviting in other

members of Trewen Community as extras and musicians, and by running

madly about with a large black cloth held above our heads. It was our

first use of Cornish folklore, and the first time we combined masks,

music and theatre to create spectacle. In other words, the basic

ingredients of Footsbarn’s style were already there.

‘Giant’ and ‘Tristan’ were important milestones in the evolution of the

company style. They were the ones the audiences remembered for years

after.

‘Crow 10’ was interesting because it was the least typical Footsbarn

production, and because we learned an important lesson from it. It was

Michael Novotny’s initiative. He had painted a series of very large

canvasses inspired by the poems of Ted Hughes. He and I agreed that the

paintings should be treated as the equal of the actors, that the

scenography should be the star players.

It was a bizarre aesthetic experiment, and there was a general air of

scepticism among the rest of the company. How dare we take ourselves so

seriously! Little absurd scenes of domestic life were inserted between

the frames, such as a woman falling face forward into her bowl of

breakfast cornflakes. And yes, we were serious, and the more we

struggled with the material, and the more scepticism we met, the more

serious we became. We were creating a beautiful but remote little work

up there on Falmouth Arts Centre’s proscenium stage. We were in trouble.

Suddenly Richard and Dave appeared in front of the stage like two

irreverent crows, dressed in black and chugging down two very white pint

bottles of milk. Their original intention may well have been to take the

piss out of the production, but they wound up discovering the audience

and ‘selling’ the show.

We learned how comedy and self-irony can build an audience’s trust in a

production, so that they become willing to enter into more dangerous

territory.

How did the Footsbarn style evolve during this period, and to what

extent was this style shaped by the context of Cornwall?

Footsbarn owes Cornwall an enormous debt. It is a classic example of

discovering universal relevance through concentrating on an individual

case. By focusing on the specific, namely what would work for a Cornish

audience, Footsbarn discovered a theatrical language with universal

appeal.

Cornwall was to be our laboratory. We were very clear and up front about

this. We were going to research theatre in terms of the audience, a

grass roots audience, and Cornwall was going to provide us with an

unspoiled environment. We didn’t want audiences with polite conditioned

reflexes. It was pointed out to us that, mostly, the Cornish hadn't seen

anything like us since before the Wesley brothers came preaching down

the peninsular. I think we were as evangelical as they in our faith in

the power of live theatre!

The first efforts included works by Ionesco, Beckett and Albee, and some

abstract clown and mime pieces. We did some good work, it gave us some

legitimacy with the regional arts environment, but as you can imagine it

didn’t really connect with our target audience of farmers, tin miners

and fishermen!

From the beginning we looked into Cornish folklore as a source of

relevant material and it soon became clear that we were on the right

track.

Oliver came up with the idea of the May Tour, in which we would play out

of doors, live in tents, ‘bury the chequebook,’ and live off passing the

hat.

So we did endless parades through small villages and sprawling council

estates, playing music, shouting through megaphones and banging drums to

round up an audience for the show on some village green, town square or

circus pitch. Here are the words to one of the songs we sang, to the

tune of the Furry Dance:

Footsbarn has come to town:

Jugglers, acrobats and clowns.

Footsbarn has come to town,

All the children dance around.

Come and see it’s a very funny play

We’ll put on for you today.

Seven o’clock the show begins;

Up my kneecaps, down your shins.

I can remember the first time a member of the audience, a first timer,

came up after the show and said 'Fantastic! It was just like being

inside a television set!'

The other dimension to our work was that Oliver and I were aware that we

had taken very different trainings, as had also the people we brought

with us. Oliver’s training was more verbal and ‘method,’ and mine

physical and expressive. We set it as a basic task for each ‘camp’ to

teach the other what we had learned in the two and a half years since we

had last worked together in Vermont.

When Footsbarn finally left Cornwall, they went off to find appreciative

audiences as young and anarchic as themselves in the hip and fast moving

European festival scene. What worked in Cornwall could also work in

Amsterdam. But without Cornwall there was an empty hole. Luckily their

tastes and travels would continue to bring them into close contact with

rural and indigenous peoples.

They continued to draw inspiration from the diverse cultures they met in

such far flung places as Alice Springs, the Portuguese mountains, Bali

and Kerala. Footsbarn is still connecting with the individual, and

rediscovering the universal.

Were you aware of other theatre companies attempting something

similar at the time?

There was really nothing like us in Cornwall. We would occasionally

discover pockets of sympathetic amateur theatre activity, for example in

Davidstowe. And of course there were such places as the Minack Theatre

and Falmouth Arts Centre, but they were more interested in bringing high

culture down from London, instead of going out and learning from a rural

audience.

There were two companies in Devon that were also under South West Arts

Association's wing, Medium Fair (John Rudlin) and The Orchard Theatre

(Andy Noble). They, like us, were interested in bringing theatre to a

rural audience. We met on the SWAA's Drama Advisory Panel. Also a few

nationally touring groups made an impression on us: The People Show and

Brighton Combination, for example. I remember Welfare State setting off

flares and accidently bringing out the Cornish lifeboats!

The Guardian journalist, Allen Sadler, took a very generous, nurturing

approach to our work. It is all too rare that reviewers understand that

their responsibility is not just to their readership, and that there are

such things as artistic potential, growth and evolution, and that it is

still possible to maintain journalistic independence within a longer

term dynamic relationship with the subject they are reviewing.

I remember Sadler asking us, and I smile warmly as I remember it, 'Don't

you ever think about asking questions about society's problems in your

plays? You don't have to provide any answers!'

I think many people were surprised that Paul Foot's brother (and Michael

Foot's nephew) should be so apolitical. Oliver was not interested in

politics, but he was a charismatic diplomat, talents he would later put

to good use as the director of the Orbis flying eye clinic.

You started Footsbarn Theatre motivated by some high ideals. But

was there anything that disappointed you about your time with them? You started Footsbarn Theatre motivated by some high ideals. But

was there anything that disappointed you about your time with them?

Yes, of course. Trewen Community was hardly an homogenous group, but

perhaps one could say that among the active members there were those who

accepted the marginal life style as a necessary compromise in order to

pursue their art, and there were those who saw their art as a convenient

means to support their chosen way of life. This contrast was a frequent

source of tension.

For me it was not so much a question of 'Who is pulling their weight and

who not?' That question was too hard to judge, one could never expect

equality, and eventually it tended to sort itself out. What I found

disturbing, and eventually very painful, was that the same buoyant,

devil-may-care, finger-in-yer-face attitude that made it possible to

survive against all odds, and was instrumental in generating a gutsy

theatre style, frequently erupted into reckless behaviour that

jeopardised this project that was my life’s dream.

'Frequently erupted into reckless behaviour!'... Well I won’t go into

the sensational details, but, more to the point, you can already hear

how prudish I sound. In a world of anarchy it is easy to sound like a

moralist. But I had a lot invested in this project. I had worked with

Oliver on the planning for over three years before we even started in

Cornwall, and dropped out of college to do it. I had no other plan.

Anything that threatened to alienate our audience I found deeply

upsetting.

Another one of the things that began to disappoint me about the company

in the time before I left is that the members were often very cynical

about certain kinds of people in the wider community that were willing

to help us, by whom I mean the middle class, established, intellectual,

artsy-fartsy, culture vultures and liberal masochists. They were not our

target audience, but they tended to be active in their communities,

loved our work and offered encouragement. However, we were just not

willing to forgive them their vicarious pleasures at seeing us fulfil

their romantic dreams. But, my god, they forgave us for so much!

How did you leave Footsbarn?

Anyone who has spent a significant slice of time working with Footsbarn

has dealt with the question 'Is There Life After Footsbarn?' It always

seemed like what we were doing was immensely important, heroic,

pioneering stuff and to leave the struggle would be an act of cowardice

and condemn one to eternal insignificance.

I had always seen it as a four year experiment. In some ways I had

trapped myself in my own ideology. When there was any discussion about

taking a show up to London I would argue that London should come down to

Cornwall and see us in the proper context. And after all, it was fifteen

years before Molière took his company into Paris! I realised later that

I had been starving for input and inspiration.

I was only able to leave in good conscience by joining an even more

brutal operation: a traditional circus with king poles bending from

metal fatigue, lorries without functioning footbrakes, a shelf in a

horse wagon for a bed, hands calloused from swinging fourteen pound

sledges, supercilious camels, neglected bears, and lions in derelict

wagons competing to decapitate their alcoholic trainer. I joined to work

on the tent, and got pushed into the ring to be a clown. It was very

hard work. It felt like being in a guerrilla band moving through enemy

territory.

The performance itself was an anticlimax. One was so numbed by fatigue

that one could even forgive the feeble attempts at aesthetic values

expressed by the artists in their personal choices of fishnet stockings.

But the strangest thing to adjust to after all those years of brown rice

and beans was being paid in hard cash!!!

Some very fine people came in and out of Footsbarn after I left, and my

biggest regret is that I didn’t have the opportunity to work with them.

However, one has to remember that as in so many fields, from IT startups

to travelling theatre companies, some people are the initiators and

others are more suited to sustain a project.

I think of Footsbarn as a kind of benign disease that incubated while I

was there, and went on to infect many other people.

When I came back to Cornwall after a couple of years to see the

production of ‘Arthur’ I was blown away. The style we had dreamt of had

arrived. In spectacle, story, character and atmosphere, ‘Arthur’ was

‘it.’ I realized that Footsbarn was still my favourite theatre company.

JP Cook's personal website:

http://www.jpcook.dk/jpc_cv.html

Footsbarn Theatre:

http://www.footsbarn.com/en/

If anyone reading this has more photos, memorabilia or memories

relating to Footsbarn in Cornwall please contact

rupert.white@virgin.net

(also see feature 'Footsbarn

Flyer')

|