|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

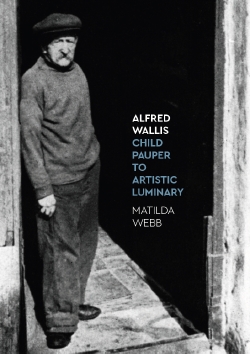

Matilda Webb on 'Alfred Wallis: Child Pauper to Artistic Luminary' e-interview Rupert White

From an early age, my favourite place was my Gran’s painting shed in her garden in Pembrokeshire. It smelled of paint, turps, old canvasses and strong coffee, and one wall was lovingly plastered in images of ships and boats by Alfred Wallis that she had cut out of magazines. My parents and brothers were also artistic, and talk at home often centred on paintings, particularly those of the St Ives artists. But it wasn’t until 2017, when I went to Kettle’s Yard to see their large collection of Wallis’s paintings in person, that I really fell in love with his work. I knew Wallis often said he painted from memory, and I felt drawn to uncover the life experiences that had inspired the heartfelt images before me.

What kind of research did you do? How did you get started? As well as a writer, I work in museums and my curatorial instinct kicked in. Armed with a list of titles of Wallis-related books and articles held in the Tate Library, I tracked these down online as cheaply as I could. As I read through them, I was struck by how little of Wallis’s own story was known. Greater focus seemed to be on the artists he influenced, and familiar anecdotes regarding his interactions with them, which were repeated without question. The last item on the Tate’s list was a Master’s thesis in New Zealand. I contacted the author, and when she asked me why I wanted a copy, I said I was thinking of trying to write an in-depth biography about Wallis. As I wrote these words, I realised that was exactly what I wanted to do, little knowing the research would take me eight years to complete!

There must still be archival information that's not really been properly studied, especially family trees... One of the first clues to unlocking the secrets of Wallis’s little-known earlier life was to obtain the certificate of his parents’ marriage, held at Penzance in 1844. It enabled me to trace generations of his mother’s ancestors to the Isles of Scilly, and generations of his father’s ancestors to West Cornwall. The certificate also gave his father’s occupation as ‘sailor’. This prompted the first of my many visits to archives around the country, initially to the National Archive in London. I spent long hours there pouring over mid-19th century documents listing the crews of Penzance-registered ships, and was excited to find not just the name of Wallis’s father and the ships he crewed on, but also those of Wallis’s maternal uncles. After that, I combined visits to archives with online research into shipping records, old newspapers, family history and more, to build up a comprehensive account of Wallis’s ancestry, his impoverished childhood, his dangerous work as a fisherman and mariner, and his subsequent life on land as a marine stores dealer and family man in Penzance and St Ives. My research was supplemented by oral history recordings of those who knew Wallis at St Ives, made in the 1960s, and by the recollections of Wallis’s living descendants, who have all been incredibly helpful and supportive. One of these, Den Ward, now aged 90, told me of the time he visited Wallis as a boy, and how he gave him several paintings and a model boat, which I was thrilled to hold in my hands. These personal stories helped counterbalance the myths repeated in earlier sources about Wallis’s supposed isolation, enabling me to build a fuller picture of his life at St Ives.

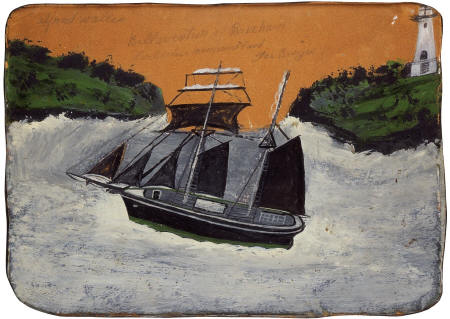

It was already known that Wallis went to Newfoundland in 1876 in the dried cod trade, but I was able to find out more about his time there, which was one full of adventure. He survived at least three terrible storms, the first of which damaged his ship and pushed it off-course to a little bay in Nova Scotia. Through my discovery of the name of a ship Wallis often spoke of - the Recruit - I was able to establish that he then sailed to the remote shores of Labrador for several months, to a settlement called Batteau, and I detail his time there using contemporary accounts and analysis of his paintings. It was after leaving Batteau in October 1876 that his ship, the Belle Aventure (depicted with black sails above left), encountered a severe storm in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. He and his fellow crew mates only survived by throwing a large part of the cargo of fish into the sea. Sadly his friends on the Recruit, which had left the day before, were lost in the storm without trace - a tragedy Wallis talked of for the rest of his life. Wallis was at sea from May to November 1876, and the harrowing experiences he underwent led him to give up life as a merchant mariner as soon as he returned home to Penzance. Life was tough and dangerous on the small, two-masted topsail schooners that traded across the Atlantic. He was an Ordinary Seaman, which was the lowest rank on the ship, and meant his quarters were in the cramped, dank and dirty forecastle beneath the deck at the prow of the ship. Shipwreck was commonplace, partly due to overloading of cargoes by unscrupulous owners, and it wasn’t until shortly after Wallis left the sea that the maximum-load line introduced by Samuel Plimsoll in 1876 was enforced.

His life at sea sounds really gruelling! Coming to his art work, is it true that he took up painting after his wife died? When was this? It is often misquoted that Wallis ‘took up painting for company after the death of his wife’. Susan died at St Ives in 1922 and there is no doubt her loss affected him deeply. Sven Berlin, who first wrote about Wallis in the 1940s, was told by Wallis’s friends that he started painting in August 1925, telling them “I dono how to pass away time…I think I’ll do a bit’a paintin’ – think I’ll draw a bit”. The year 1925 is significant. While his birthday is celebrated each year by the Tate and Kettle’s Yard on 18th August, his birth certificate shows he was born on 8th August, and he would have turned 70 on that date in 1925, making him eligible for the Old Age Pension. Having worked all his life, receiving a pension meant Wallis finally had a reliable income, and his thoughts had turned to finding himself a hobby. The reason he chose painting, and the inspiration for his work, are detailed in the latter part of the book which looks in detail at his time as an artist.

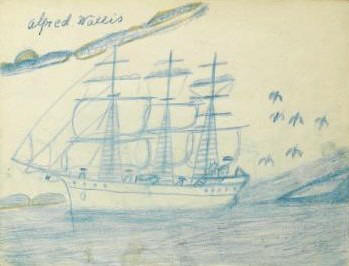

Yes, I would agree. Having seen a large number of his paintings, I can discern certain elements that reveal from which period the work belongs to, but by and large his style and approach remained the same. His subject matter remained constant too. It is interesting to note that he was painting other subjects besides ships and boats from very early on, particularly scenes of houses, and he drew the same subjects in the sketchbooks he filled in when he was in the workhouse at Madron in the final year of his life. Throughout his 17 years of output from 1925 to 1942, Wallis used the same supports of cardboard and paper, and the same boat paints made by Peacock & Buchan. This is an interesting point because it is often stated that he used these materials due to lack of funds, but my research shows they were conscious design choices. Even when he was in the workhouse, for example, Wallis asked for his usual boat paint to be brought to him from his supplier in St Ives. Overall, it can be said that Wallis executed his paintings in a style wholly his own, without regard for any art movement, and I believe this is why they still hold such great appeal for each new generation of admirers.

I have a sense that Jim Ede was probably the most supportive of the artist-collectors that he met. Certainly he seems to have bought large numbers of paintings that have ended up at Kettle's Yard. Can you comment on this and on the support he did (or didn’t) receive from other artists? This is a difficult topic that many people ask me about, and many have speculated on ever since Sven Berlin first raised it in his 1943 Horizon article. In attempting to write as complete a biography about Wallis as possible, I felt the need to address this issue head-on, so it underpins the latter part of the book. I uncovered evidence in original material from Jim Ede, Ben Nicholson, Margaret Mellis, Sven Berlin and others to show that the support Wallis received did not equate to his increasing artistic standing in the British Modern Art world during his lifetime. I’d love to share more here, but I think it’s important to allow readers to come to their own conclusions. To this end, I have presented the contemporary evidence in as balanced a way as possible in the book, to allow the facts to speak for themselves.

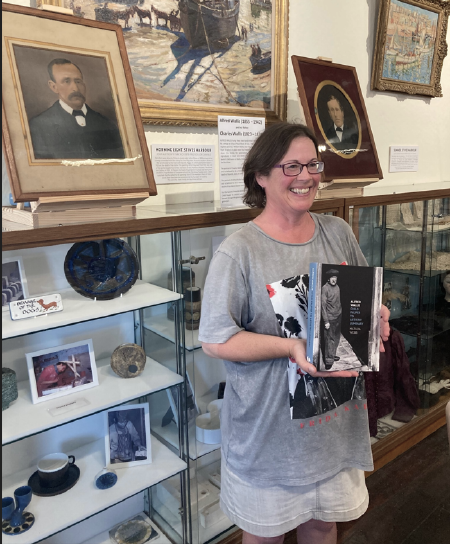

I loved every aspect of the eight years it took to research, write, and produce this biography. It was deeply rewarding to uncover so much new information about Alfred Wallis’s life and to use those insights to reinterpret some of the paintings I first encountered at Kettle’s Yard back in 2017. TJ Clays in Padstow did a wonderful job printing the hardback, with beautifully faithful colour illustrations - I'm absolutely delighted with the result. More than anything, I hope the book offers a fuller, more accurate picture of Wallis - not just as a painter, but as a loving family man who lived through enormous hardship and was able to express this late in life through his paintings. If readers can come away seeing his work with fresh eyes - seeing not just the charm but the strength and experience behind them – I’ll feel truly glad.

Alfred Wallis: Child Pauper to Artistic Luminary by Matilda Webb is available here: https://www.alfredwallis.co.uk |

|

|

Can

you say something about your background, and what led to you

Can

you say something about your background, and what led to you

_small.jpg)