'The St Ives artists: a biography of

place and time' is due to be published in spring 2008. There's

been a lot written about St Ives art, but in this book you're

interested in the wider cultural context of St Ives art. Is that

right?

First, the book works

as an unfolding narrative which brings together artists, places

and events with certain broad historical themes. I wanted to

tell a serious art-historical story but at the same time make it

as readable as a novel. I don't think anyone has approached St

Ives in quite this way before. Secondly, you are right that the

wider connections with what was going on in Britain at the time,

between the 1930s and the 1960s especially, are an important

part of the story. While other writers on St Ives art have

certainly explored these connections, they haven't generally

used them in a structural or thematic way.

This is the short answer. I also hope that there will be more

than a few moments in the book when even people who are very

familiar with particular St Ives artists and works of art will

see them in a different light.

One

constant feature of this century and the last is the pull of

Cornwall to people who want to extricate themselves from the

routine of urban and suburban living - from the rat-race if you

like. Is this one of the themes? One

constant feature of this century and the last is the pull of

Cornwall to people who want to extricate themselves from the

routine of urban and suburban living - from the rat-race if you

like. Is this one of the themes?

MB Yes, although I look at it from the perspective not only

of the artistic 'incomers' but also of people living in St Ives

- Alfred Wallis, for one.

Urban Europeans have been trying to escape from the industrial

rat race for at least 200 years, and St Ives is just one of

places they've headed for - others being the Lake District,

Brittany, the South of France, and so on. What artists found in

West Cornwall to a large extent depended on what they were

looking for. Patrick Heron, for example, saw the landscape as a

kind of Celtic Provence - full of intense Mediterranean colours,

but this time gorse rather than mimosa. On the other hand Bryan

Wynter (picture above: 'Foreshore with Gulls', 1949), who had

been reading a lot of Jung before he moved down in 1945, often

seemed to think of the Penwith Moors as a vast granite model of

his own unconscious.

Each artist, each person creates his or her own landscape - and

yet there is this place, real and outside ourselves, which is

also a powerful part of the equation. I can't say that I have

solved this mystery, but I have tried to show how it was that so

many different artistic pathways ended up converging on St Ives.

What are the other themes, and are there

stories or individuals who epitomise them?

My original idea was that in each chapter a particular

artist and historical theme would come to the fore. So I would

look at Terry Frost in the context of new opportunities and

attitudes to the class system after the Second World War, then

the chapter featuring Patrick Heron, an early champion of

American Abstract Expressionism, would also cover the influence

of American culture in Britain during the later 1950's. In the

end, both the artists and the historical sequence refused to be

structured quite so neatly, but this is still the basis for the

narrative and I feel that on the whole it works. The

alternative, to have all the artists milling around in every

chapter, would have made it impossible to grasp the bigger

picture.

Regarding the influence of American culture on the St Ives

artists, was it limited to visual art or were other types of

Americana important too?

In the late

1940's it was a big deal for artists in St Ives if a civil

servant from the Arts Council called round for a studio visit.

Ten years later, there were visits by Clement Greenberg, Marc

Rothko (Rothko's visit picture right) and other movers and

shakers from the New York art world. British artists including

Nicholson, Lanyon and Frost had exhibitions in New York. This

was the era of what Heron later called the 'St Ives-New York

axis'.

As far as

the rest of Britain was concerned, it coincided with the 'Never

Had it So Good' years under MacMillan, when people finally had

money to spend on new consumer goods inspired by the American

lifestyle. Hollywood, rock music, washing machines, televisions;

it was an extraordinary time, after a decade and a half of war

and then austerity. It was actually a desire to write about this

era, to see where the art fitted into the rest of it, that

started me off on the book. So yes, all sorts of 'Americana'

find their way into the picture.

One of the things that interests me is the importance of Eastern

thinking emerging in the States in the 50's and continuing with

the Beats in the 60's. Via Bernard Leach, however, it had a

representative in St Ives too...

Bernard

Leach certainly features, although much earlier in the story.

Imagine this tall, serious ex-Slade student, who was now a

cultural celebrity in Japan, turning up in 1920 with his

Japanese assistant and building an oriental kiln in a damp field

on the outskirts of St Ives, as far as possible from proper

sources of clay or firewood. As a passionate intellectual and

charismatic eccentric, who showed how the spiritual marriage of

East and West could take place in a teapot, Leach established a

kind of bridgehead in St Ives for others to follow.

One way or

another, St Ives became associated over the years with various

sorts of idealistic alternative lifestyles; artists on the

moors, beatniks hanging around the harbour. I find this whole

phenomenon fascinating and had to try hard not to let it

distract me from the art.

The

'Eastern' thinking of the 1950's and 1960's was largely a

reaction to consumerist materialism, which of course was much

more rampant in California than in St Ives. The fact that

seaside towns in general were favoured spots for dropping out

didn't really have much to do with Buddhism. Many of Leach's

'Eastern' ideas, on the other hand, began as British Arts &

Crafts ideas that he had taken to Japan, along with his love of

William Blake, only to find that they coincided with a

back-to-our-roots spirit that was already prevalent in certain

cultural circles there.

Were

you able to do any new research for the book? Did you uncover

anything that had, perhaps, been overlooked before? Were

you able to do any new research for the book? Did you uncover

anything that had, perhaps, been overlooked before?

I did a lot of research in the Tate Archive, going through

artist's letters and notes. Most of this material has already

been studied by art historians, but quite often I was struck by

statements or connections that I hadn't seen anyone make before.

I did also come across new material. The Frost family very

kindly allowed me to study a notebook that Terry kept in the

early 1950's in St Ives and Leeds, full of drawings, lecture

notes and memos which cast light on a crucial phase of his

career. And there are some wonderful illustrated letters from

the poet Sydney Graham to Roger Hilton that have never been

archived or published.

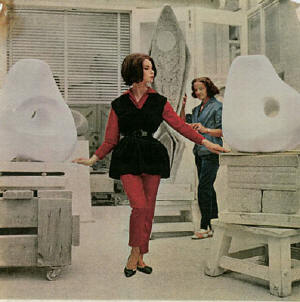

The St Ives Trust's Archive Study Centre was an invaluable

resource. One of the things I discovered while going through

their huge collection of press cuttings is how incredibly chic

St Ives was thought to be in the early 1960's - a kind of

Cornish Rive Gauche. Fashion photographers were sent down from

London to photograph the artists in their natural habitat

(picture left above: Cornel Lucas). It was all very much part of

that moment around 1960 when British art and fashion suddenly

started to interact - quite different to the high-minded

Modernism we associate with the St Ives of Ben Nicholson and

Barbara Hepworth.

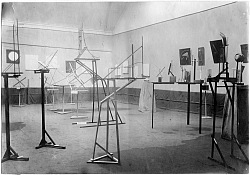

Hepworth doesn't look too approving

in that picture! I guess by the sixties the idealism of early

abstract art present especially in Naum Gabo and Russian

Constructivism (picture below right: first Constructivist

exhibition) had largely ebbed away and what was left was 'a

look' - and perhaps a lifestyle idea that could be easily

packaged.

This was the time when eg

Bridget Riley had started making art that had much in common

with Hepworth's except that it was purely retinal: a visual

effect without much in the way of ideals behind it. But how

idealistic or radical were the St Ives artists to begin with?

Was there ever a time when they were challenging and radical?

There is an important difference between being idealistic

and being radical or challenging. Gabo and other abstract

artists of the 1930's were extremely idealistic. They believed

that art could lead the way towards a better society. But at the

same time they more or less accepted that very few people would

understand their work, or even be interested enough to find it

'challenging', because they were way out ahead of the field;

avant-garde, in other words.

After the war, Peter Lanyon and other artists in St Ives

inherited a lot of this 1930's idealism. With the new Labour

government, the Welfare State and other social changes, however,

came a general feeling that everyone - doctors, teachers,

artists - should be doing something useful to support this

better, fairer world. This was a problem for painters,

especially. You could radically explore the depths of your own

psyche, or the forms of the Cornish landscape, but how would

this improve other people's lives?

There was much talk about artists collaborating with architects

in the task of reconstruction, making spaces that people could

actually live in. For someone of Roger Hilton's self-critical

intelligence, the question 'What is the point of painting?' was

a constant torment. He felt driven to do it, yet he couldn't

help but see that it was a socially marginal activity.

The early Modernist idea that artists had to be radical or

challenging to be worth looking at really bounced back during

the 1960's with new approaches that had a strong ethos of social

critique. Before this, for a decade or so after the war - the

high-point of modern art in St Ives - it was quite difficult to

shock people anyway. They had been bombed, bereaved, traumatised

by combat, surrounded by urban wreckage; what sort of shock

could you add on top of all this?

The other thing that had happened by

1960 was the emergence of American art. You've mentioned Patrick

Heron. What do you make of his writing on the subject? He

claimed, if I understand correctly, that the St Ives artists had

been doing abstract expressionism for some years, but that

American critics had refused to recognise this. He likened it to

cultural imperialism. Is this - or Patrick Herons writings in

general - something you explore in the book?

Yes, I make quite detailed reference to Heron's writings at

various points. He wrote so well about painting, and he

deliberately tried to give critical shape to an idea of St Ives

art that included himself and his friends: Lanyon, Wynter, Frost

and Hilton.

His thoughts about American Abstract Expressionism changed

significantly during the later 1950s. In early 1956 he was one

of the only British critics to applaud the big American show at

the Tate - the first time many artists in this country had seen

work by Pollock, Kline, De Kooning and Rothko. Within a couple

of years, though, he was back-pedalling and starting to talk

about cultural imperialism. He realised that the power of the

New York art market to make reputations was completely

overshadowing his efforts to promote British painters. He wasn't

alone here - in general, before people started to get excited

about Pop art and it became clear that Britain could never stem

the tidal wave of American imports, there was constant

bellyaching by British intellectuals about American culture's

brashness and supposed lack of depth.

Thinking about art and fashion and

other cultural cross-overs I am sometimes surprised there

weren't more. One of the best examples was Terry Frost's 'Walk a

long the Quay' (1951 - left) being used as a cover for one of

the famous Blue Note Jazz albums.

Can you think of other more substantial

'cross-overs'? Do you think Cornwall's geographic isolation was

to blame for the fact there weren't more?

The

obvious point here is that if Cornwall were more like Surrey or

the Cotswolds - a short commute from London - it wouldn't

have attracted the kinds of artists that it did. I also think

that many artists find that their work is constantly being

enlivened by crossovers. Wynter was fascinated by natural

history, Nicholson loved ball games, Frost read poetry, Lanyon

was addicted to fast driving; all these things fed into their

art. Whether the crossovers ended up being part of the way the

art hit the marketplace, like an album cover, was often down to

chance: who you happened to have lunch with, what the friends of

your friends were into. The

obvious point here is that if Cornwall were more like Surrey or

the Cotswolds - a short commute from London - it wouldn't

have attracted the kinds of artists that it did. I also think

that many artists find that their work is constantly being

enlivened by crossovers. Wynter was fascinated by natural

history, Nicholson loved ball games, Frost read poetry, Lanyon

was addicted to fast driving; all these things fed into their

art. Whether the crossovers ended up being part of the way the

art hit the marketplace, like an album cover, was often down to

chance: who you happened to have lunch with, what the friends of

your friends were into.

Of course, these encounters take place much more routinely in a

city; there aren't many fashion houses or film studios in

Cornwall. But then I think of a contemporary artist like Andrew

Lanyon, who uses photography, film, assemblage, writing and even

paint and I reflect that being in Cornwall is no barrier to

moving between different media. It probably takes a high level

of determination and independence of mind to do really good work

down here. There is much less money floating around, and fewer

people who crave the sheer breadth of cultural activity you get

in a city. And I'm very sceptical about that phrase that crops

up everywhere - 'inspired by the Cornish landscape' - like 'Made

with Real Lemons'!

Finally, I'm not sure that we can usefully compare the 1940s or

even the 1970s to the situation today, when global

communications can instantly link creative thinkers in any part

of the world. If an artist can't think creatively enough in

Cornwall, there's probably a good reason why he or she needs to

move on.

'The St Ives artists: a biography of time and place' will be

available in Spring 2008

'Sandra

Blow' is available via Amazon and all good booksellers

interview by Rupert White |