|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Kenneth Martin and Mary Martin Constructed Works Tate St Ives 6th October 2007 - 13th January 2008

A spare - and colourful - geometric elegance permeates Kenneth Martin’s and Mary Martin’s ultra-modernist works on display at Tate St Ives this month.

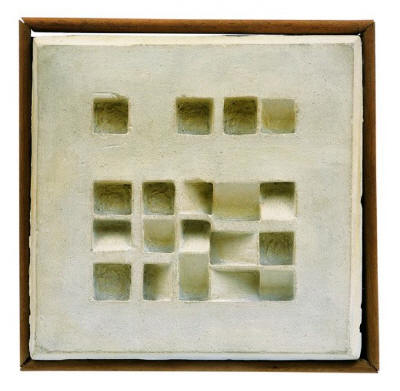

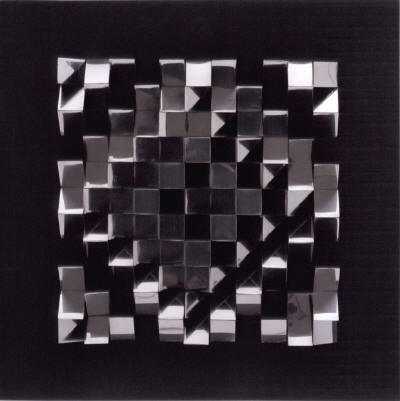

Perhaps the term ‘mobiles’ misrepresents the complexity of Kenneth’s air-borne kinetic sculptures and Mary’s reliefs created in Perspex, plaster and stainless steel, materials more akin to industry than art, diminishes their significance. Their work is iconic. Retaining the concepts of the earlier Constructivists, who believed art should directly reflect the industrial world, Kenneth and Mary’s artworks are like time capsules. During the period after the Second World War, anyone working in an abstract idiom was marginalised, as they were working against a tide of representational and figurative artists, who were producing realist ‘kitchen sink’ paintings – the visual equivalent of John Osborne’s angst-ridden plays.

Kenneth and Mary sought to make ‘a popular art from the difficult and culturally elevated ground of pure abstraction, creating work which was spare and austere with elegant sinuous lines.’ They used primitive forms, circles and ellipses, to convey complex ideas, including the molecular structure of DNA strands, often building on something more idealistic and irregular than just angles and fractions. And, unlike Nuam’s constructions which appear self-contained, composed within their own internal spaces, Kenneth and Mary’s work is ‘expansive and open, piercing the space surrounding it.’

Believing

practising artists have a social role to perform with potential to

influence people’s lives, Kenneth and Mary were instrumental in placing

art within the public arena. Mary carried out several architectural

commissions, including a piece called Wall Construction, Musgrove

Park Hospital which ‘was intended symbolise, on the personal scale,

the Of course, Tate St Ives was designed to display modernist artwork and, despite being within a gallery space, this exhibition highlights the role art performs in public. As Libby Purves said, “Artists envisioning public works are in a unique position. Many people, who never voluntarily go into an art gallery, walk past a sculpture every day and grow fond of it. Thus the mass of us enter into the vision of the artist and are almost imperceptibly enlarged and enriched by that unsought communication.” Kenneth and Mary’s work affirms this belief. This combination of Kenneth’s mobiles and his Chance and Order series of abstract paintings, and Mary’s elegant relief-sculptures, offers Tate St Ives visitors an unrivalled opportunity to examine a focused body of work by a pair of significant modernist artists.

Peta-Jane Field article appears courtesy of 'Inside Cornwall'.

|

|

|