|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

Art in aspic: rural artists breaking free from the mouldAlex Murdin

It’s a well know fact that the countryside is the graveyard of artistic ambition. The typical cycle of regional artists moving to the city to make their name and then “retiring” to countryside once this has been achieved is a common preconception. Damian Hirst, born in Bristol and now resting on his bank balance in Ilfracombe, comes to mind. The questions this raises though are, is this purely an economic decision - the cities are where the international galleries are - or is it more to do with the idea that the countryside as a site of artistic enquiry is incapable of moving beyond the clichéd Romantic utopias that both artists and our political systems preserve in aspic ? Are there rural subjects and spaces out there that allow for a more critical reflection on landscape as a cultural construction ? Can the rural be taken apart and put back together by a new generation of politically and socially engaged artists ? There can be no doubt that rural spaces in the UK tend to be perceived as spaces in the service of the urban majority. This is apparent geographically, as 90% of the UK’s population live in urban environments, even if 80% of the land is rural[i], and historically, as the countryside that has been the site of agricultural production has become increasingly the site of the production of amenity for the city. Culturally the countryside still has a symbolic position for sections of contemporary British culture grounded in 19th century Romantic literature and landscape imagery and now interwoven into a global idea of the English landscape. For example textual readings of landscape regularly refer to English landscape in attempting to deconstruct the mythological, narrative and symbolic meanings of contemporary modes of landscape production: “The English landscape style spread throughout the British Empire and beyond. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century garden suburbs in England and North America adopted it, and so, more recently, have corporate office parks, asserting the power of property, the status of the owner, and alluding to the continuity of Western culture.”[ii]

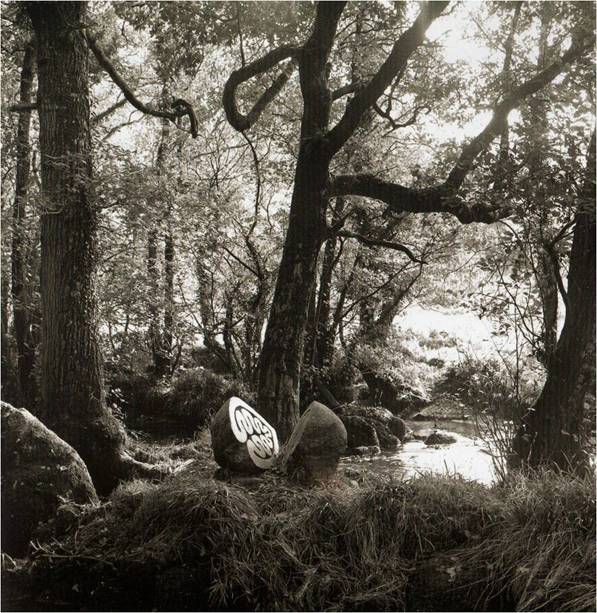

England, Richard Long 1968

Equally the English landscape is associated with the individual and Romanticism, the idea of being inspired spiritually and intellectually by nature, wilderness and solitude. A contemporary re-interpretation of Romanticism as it relates to the English landscape can be found in the work of Richard Long. His walking artworks made from 1967 onwards explore transient, phenomenological responses to landscape. He identifies walking with spiritual enlightenment and transcendental traditions: “Walking itself has a cultural history, from Pilgrims, to the wandering Japanese poets, the English Romantics and contemporary long-distance walkers”[iii]. Through his walking works Long suggests that he is fulfilling a basic need to explore, to expand our understanding of the world and to reconnect to nature, searching for spiritual experiences in the land. Long could be seen in this light as the embodiment of artist as spiritual tour guide. As the writer John Urry says in The Tourist Gaze: “All tourists…embody a quest for authenticity, and this quest is a modern version of the universal human concern with the sacred. The tourist is a kind of contemporary pilgrim, seeking authenticity in other “times” and other “places”, away from that person’s everyday life.” (Dahlgreen, 2005: p.48) [30][iv] The critic Rebecca Solnit suggests that Long’s work is also a response to peculiar national, spatial qualities. Contrasting his work to American Land Art being made within the same timeframe by artists like Robert Smithson, which are of monumental scope, she states: “England on the other hand has never ceased to be pedestrian in scale, and its landscape is not available for much further conquest so artists there must use a lighter touch.” [v] The utopian “green and pleasant land” of William Blake and other Romantics, still plays a significant part in constructions of [English] national identity, as does its counterpart the dystopian polluted, industrial city. This has meant that the countryside is increasingly a contested political space as, for the first time since the industrial revolution, migration from the countryside to the city has been reversed over the past 10 years: “Very consistently… it seems that the more rural an area is, the more it gains migrants…the ‘quest’ for a rural idyll is stronger than the negative aspects of urban life.”[vi] However the rural idyll itself is often negated by the act of seeking it. Conflict often occurs in rural locations between indigenous agricultural populations and retiring or downsizing, second home-owning, incomers who have visited or moved to the countryside for its amenity or leisure value. This seems though to be an inexorable march. The mass trespasses in the name of access by urban working class groups, including the British Communist Party, in the 1930s, the establishment of the National Parks from the 1950s onwards in the cause of an aesthetically inspired conservation agenda, and the more recent Countryside Rights of Way Act, 2000, have all exemplified a continuing appropriation of the countryside in the service of recreation for the urban majority.

Vixen Tor Protest March, Alex Murdin, 2008

In The death of rural England (2003) Alun Howkins suggests that the increase in the recreational use of the countryside, along with the organic food movement and epidemics such as Bovine Spongiform Encephalitis and Foot and Mouth disease, will be a major contributing factor to a significant rethinking of the rural. He states that the Foot and Mouth epidemic in 2001 had “revealed just how “non-agricultural” rural England had become…the English Tourist Board estimated that the tourist trade was losing £250 million a week while farming was losing only £60 million.” [vii]

Gortex, Tania Kovats, 1997

Leisure use of the countryside by visitors, both domestically and internationally, has a high economic value to rural communities and hence to those agencies and organisations responsible for conceiving and constructing the spaces of representation relied on for branding and marketing the countryside. Devon based artist Tania Kovats comments on this ironically in her work Goretex, “I can’t recommend Goretex highly enough. My two-way front zipped with raingutter flaps, rugged windproof nylon shell, Velcro closure cuffs, and fully breathable layer. Goretex waterproofs have to be the ideal choice for what to wear in Utopia.”[viii] The implied freedom and accessibility inherent in the marketing of countryside is, however, ultimately contradicted in practice by the management practices of large private estates and public sector land owners. In their book Contested natures, Mcnaughton and Urry undertake an analysis of what they call “landscapes of discipline”. Assessing the language of government agencies (Sport England, the English Tourist Board and the Countryside Commission) they identify the continuing primacy of a Romantic gaze; “the model of the person presented is of a privatised individual experiencing and consuming qualities associated with a national beauty (true England).” [ix] They go on to argue that this has the effect of disconnecting the subject (the viewer) from the object (landscape) through the mechanisms of leisured, aesthetic appreciation e.g. walking, motoring, caravanning, photographing and painting.

These passive modes of experiencing the countryside are re-enforced through overt legislative codes and through self-surveillance. The Countryside Code emphasises the transient nature of participation in rural spaces for the visiting public: follow the path, keep dogs under control, take home litter, etc. Even farmers who were “landowners” are now temporary “land stewards” in land management terminology. The invocation of the authority of environmentalist conservation agendas balancing regeneration and conservation (for instance in reconciling the oxymoron of sustainable tourism) is common, where it is also used to justify modes of passive consumption. All of these strategies decrease the likelihood of experiences of the countryside that can express alternative visions of its physical and social future: “These issues need to be recognised as cultural dilemmas requiring political responses, before they can be addressed by management or a planning system primarily concerned with competing land uses and the negotiation of physical pressures“ (Mcnaughton and Urry, 1998).

What about the place of art in this ? The organisation Common Ground is well known for commissioning artists in rural contexts. One project they worked on, a sculpture project called the Silkstones Heritage Stones, shows that art in rural locations is also subject to this discipline. One respondent to the evaluation of the project firmly locates art within designated parameters: “We have a very large sculpture park, approximately 3 miles away. If you wish to display your work there, we will go and see it! What we don’t want is to have to walk past it everyday of our lives.” This attitude is perhaps informed by the zonal land management practices identified by sociologist Howard Newby as a form of “apartheid”: “Environmental bantustans are set aside where virtually unrestricted leisure activity is allowed and even encouraged, so that the surrounding area can be strictly controlled and rationed for those interested in a more solitary appreciation of the countryside.” [x]

Postcard for the Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Complicity by artists and curators in this ordering of the way art is experienced in the countryside is now being questioned. The Grizedale Sculpture Trail in Cumbria, established in 1977, has now rejected the format of the park or trail as a “cultural silo” and states on its website that: “Rather than aiming to create a finished product for public consumption, the programme places an emphasis on process, the dissemination of ideas; we are currently trying to make this process accessible to a wider audience.”[xi]

However artists working in the countryside, and those that commission them, often re-enforce passive/disciplined modes of visual consumption in spite of intentions to the contrary. Sculptor Peter Randall Page has been instrumental in bringing public art to the countryside through his work for Common Ground. Through one of their joint projects, which took place from 1990 to 1995, a series of stone sculptures based on trademark seed forms was created in and around Drewsteignton, Dartmoor on accessible sites, alongside paths such as the Two Moors Way and on National Trust land. Common Ground aimed to use art to develop a more particular sense of place in this rural location, challenging common understandings of beautiful landscape. Sue Clifford, the Director of Common Ground, stated:

“Through our work on Local Distinctiveness, we have tried to liberate us all from the preoccupation with the beautiful, the rare and the spectacular to help people explore, express and savour what makes the commonplace particular.” [xii]

The project has been a great success in that local people value the works' empathy with their Dartmoor setting. As the Town Clerk commented at the time, the works were in the “right place, doing what was intended, focussing my eye on a particular part of the landscape” (Chapman and Randall Page, 1999: p.82). Nevertheless there is a sense in which the work, by creating focal points in the landscape, inevitably counters the stated intention of the project in promoting the commonplace, as the objects created become destinations in their own right, the subject of publications, articles and catalogues albeit primarily marketed to the privileged cognoscenti of the art world.

Granite Song, Peter Randall Page, 1991

Essentially passive and interpretative roles ascribed to artists are even more acutely articulated in areas which are deemed ecologically and aesthetically sensitive. In the Arts Council England policy document Arts in the protected landscape, published in 2006, a list of actions contained within the introduction shows that art “records” and “interprets” and although it is allowed that artists “create” and “explore” their role is primarily passive, to “understand”, “share”, “make connections”, “communicate”, “knit together”, “define”, “reconnect”, “record”, “protect” and “promote”. [xiii]

It is not therefore surprising that some artists and curators call for a more dynamic and strident “radical ruralism”[xiv] in response to the cultural inertia and economic consumerism that affects the rural. Many environmental (or ecological) artists have been responsible for challenging the idea of the countryside as a yet another consumable resource. There are also new breeds of socially engaged artists who are responding to the countryside in a more holistic way, putting neither culture nor nature first, but recognising that we are both part of nature and in a dynamic dialectical relationship with it. That this is true is now more apparent than ever. Some geologists are even suggesting that we have now entered the anthropocene, a geological “age of man”, in which humanity has so drastically altered the earth’s environment since the invention of agriculture that we now count as natural force alongside vulcanism and continental drift.

Immersions, Alex Murdin, 2009

Society’s management of the countryside and our cultural responses are therefore of the utmost importance in directing the course of the anthropocene. We need to recognise our complicity in the ordering of the (our) environment, as artists, as humans. We need to ask the question whether to preserve and conserve, through artistic representation or otherwise, is enough; or whether we need to foreground the countryside as a contested social and political space where artists can (and are allowed to) develop innovative perspectives and, more importantly, radical actions.

Alex Murdin, artist and curator – www.ruralrecreation.org.uk 8/10/09. A version of this essay was presented as part of This Weekend? (BOSArts 2009)

[i] Jenkins, J. ed., Remaking the landscape: The changing face of Britain. 2002, London: Profile Books. [ii] Whiston Spirin, A., The language of landscape. 1998, New Haven & London: Yale University Press [iii] Long, R., Richard Long: Walking the line. 2002, London; New York, NY: Thames & Hudson Ltd. [iv] Dahlgreen, K., Foreman, K. and Van Eck, T. (ed.), Universal experience: Art, life and the tourist's eye. 2005, Chicago & New York: Museum of Contemporary Art. [v] Solnit, R., Wanderlust: A history of walking. 2nd ed. 2002, London: Verso. [vi] Champion, T. in Flight from the cities?, in On the move: The housing consequences of migration, 2000, York Publishing Services Ltd: York. [vii] Howkins, A., The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside. 2003, London: Routledge. [viii] Kovats, T., 100% Waterproof: Goretex - what to wear in utopia, in Arcadia revisited: The place of landscape, Walsh, V., Editor. 1997, Black Dog Publishing Ltd: London. [ix] Macnaghten, P. & Urry., J, Contested natures. 1998, London: Sage Publications. [x] Newby, H., Green and pleasant land? Social change in rural england. 1979, London: Hutchinson. [xi] Grizdale arts - about us. 2008, http://www.grizedale.org/about/. [xii] Chapman, C. & Randall-Page, P., Granite Song. 1999: Westcountry Books. [xiii] Arts Council England. Arts in the protected landscape. 2008; Available from: http://www.artinlandscapes.org.uk./index.htm. [xiv] White, R. Radical ruralism: More v Social Systems: a response to Virginia Button. 2007

|

|

|