Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet

1969-2009 is an important exhibition. Much has been

written about it in the papers and on the Eco Art Network. It

is a really valuable opportunity to see seminal works by a

range of artists and architects. I hadn’t seen Beuys’

Honey Pump, nor the film of

Ukeles‘ Touch Sanitation, nor

Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty, nor any of the

Harrisons’ Survival Series (1970-1973).

Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet

1969-2009 is an important exhibition. Much has been

written about it in the papers and on the Eco Art Network. It

is a really valuable opportunity to see seminal works by a

range of artists and architects. I hadn’t seen Beuys’

Honey Pump, nor the film of

Ukeles‘ Touch Sanitation, nor

Smithson’s film Spiral Jetty, nor any of the

Harrisons’ Survival Series (1970-1973).But I finally worked out the essence of my problem with the exhibition. The title frames ‘art and architecture’ and there are works by both artists and architects included in the exhibition. The works from the 60s and 70s are radical, there’s no question about that. But the real radicalism of some of the artists and architects is in the scale of their work, and in the exhibition this is only really conveyed in the Center for Land Use Interpretation work The Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Even the film of Touch Sanitation doesn’t convey the eleven month performance of shaking 8,500 sanitation workers’ hands and saying to each of them “Thank you for keeping New York City alive.” The exhibition feels like its driven by a curatorial focus on artwork as object, rather than artwork as question or consideration of context.

The real shared territory between artists and architects is

in thinking at scale about boundary, organisation,

information, energy, metaphor, systems and people; not the

superficial similarity of objects.

The real shared territory between artists and architects is

in thinking at scale about boundary, organisation,

information, energy, metaphor, systems and people; not the

superficial similarity of objects.

Think about Hans Haacke’s 'Shapolsky et al., Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971', (left) shown at the Tate’s exhibition Open Systems: Rethinking Art c.1970 a couple of years ago where he focused on the ownership of tenements in New York by one family through a network of businesses. This would have been relevant as an introduction to social ecological concerns.

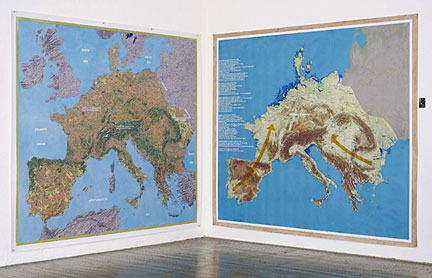

Think about the Harrisons’ work Peninsula Europe (2001-2003) (below right) which presented the European peninsula as single entity considering the role of the high ground in the supply of fresh water to the population.

Think about Tim Collins and Reiko Goto’s work 3 Rivers 2nd Nature (2000-2005) which involved the strategic planning of the whole Pittsburgh river system area. Goto and Collins “addressed the meaning, form, and function of public space and nature in Allegheny County, PA.” They developed the Living River Principles which were used as a tool for lobbying public officials. They worked with a team of volunteers to develop monitoring systems documenting land use, geology, botany and water quality.

Or

PLATFORM’s work

Unravelling the Carbon Web (2000 ongoing) which

asks us to understand the social and environmental

consequences of oil through multiple iterative works drawing

attention to the oil industry and its associated networks to

Universities, Government and other corporates, working with

inhabitants, NGOs and Unions along BP’s Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan

pipeline, and in Iraq. The purpose of this work is social and

ecological justice, but it is also to relate this distant

business to the lives of people living in London and the UK.

Or

PLATFORM’s work

Unravelling the Carbon Web (2000 ongoing) which

asks us to understand the social and environmental

consequences of oil through multiple iterative works drawing

attention to the oil industry and its associated networks to

Universities, Government and other corporates, working with

inhabitants, NGOs and Unions along BP’s Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan

pipeline, and in Iraq. The purpose of this work is social and

ecological justice, but it is also to relate this distant

business to the lives of people living in London and the UK.

Or Peter Fend, one of the most interesting artists, whose work with the Ocean Earth Development Corporation actively seeks to challenge the relationship between art and business by developing approaches to ecological problems through the means at the disposal of artists - colour theory, conceptual synthesis and the use of emerging tools such as satellites.

All of these works:

- Are of a scale which touch on or encompasses whole political, social and ecological systems.

- Involve communication between artists, scientists, politicians and inhabitants (i.e. in multiple and complex ways, rather than from singularly from artist to audience).

- Foreground the connections between living and non-living structures, such that the work is relevant to our daily lives, rather than objects for aesthetic contemplation.

- Blur the idea of the artist, raising the question “is it art?” because the work and the artist are also economist, environmental scientist, planner, etc..

- Raise the question, “Who made the work?” breaks down the idea of the artist as individual, because the work is made through the input of a range of people.

- Embody diversity of description (something very problematic in museum contexts).

- Embody and make relevant all phases of the life-cycle of the art.

Whilst much of the work in the exhibition is also

characterised by the above points, it has not been chosen to

emphasise these points. Rather it has been chosen because it

meets a different set of criteria, criteria of objectness.

Thus there are at least five works that involve plants in the

gallery - Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison’s Farm,

Hans Haacke’s Grass Grows, Simon Starling’s boat for

rhododendrons, Henrik Hĺkansson, Fallen Forest,

2006. But the differences between these works, between ironic

comment and practical application is lost. The Harrisons’

work is of a practical character “What can we do in these

circumstances?” where Starling’s work has an ironic purpose,

raising questions about nativeness and protection. Haacke’s

work Grass Grows is a work that demonstrates the

Manifesto he wrote in 1965,

Whilst much of the work in the exhibition is also

characterised by the above points, it has not been chosen to

emphasise these points. Rather it has been chosen because it

meets a different set of criteria, criteria of objectness.

Thus there are at least five works that involve plants in the

gallery - Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison’s Farm,

Hans Haacke’s Grass Grows, Simon Starling’s boat for

rhododendrons, Henrik Hĺkansson, Fallen Forest,

2006. But the differences between these works, between ironic

comment and practical application is lost. The Harrisons’

work is of a practical character “What can we do in these

circumstances?” where Starling’s work has an ironic purpose,

raising questions about nativeness and protection. Haacke’s

work Grass Grows is a work that demonstrates the

Manifesto he wrote in 1965,

…make something which

experiences, reacts to its environment, changes, is nonstable…

…make something indeterminate, that always looks different,

the shape of which cannot be predicted precisely…

…make something that cannot “perform” without the assistance

of its environment…

…make something sensitive to light and temperature changes,

that is subject to air currents and depends, in its

functioning, on the forces of gravity…

…make something the spectator handles, an object to be played

with and thus animated…

…make something that lives in time and makes the “spectator”

experience time…

…articulate something natural…

|

The off-site project 'Dalston

Mill', is a more interesting work than some in the exhibition,

precisely because it was not curated, but rather made. Developed by

EXYZT, the Paris based architectural practice that designs, builds and inhabits its own projects, Dalston Mill takes on some of the challenges which are marked out in the exhibition. |