|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Tanya Krzywinska and Ruth Heholt's 'Gothic Kernow: Cornwall as Strange Fiction'. Francesca Bihet

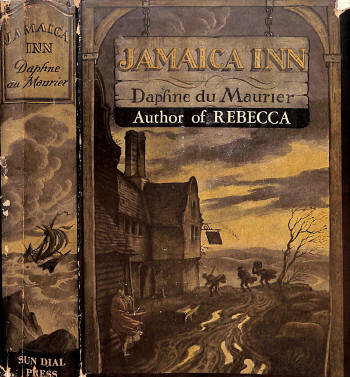

In this volume Tanya Krzywinska and Ruth Heholt, both based at the University of Falmouth, challenge the superficial image of Cornwall and consider instead a Cornish Gothic based in literature, art, and film, emerging from the county’s wild and mystical landscape. Gothic Kernow forms part of the Anthem Studies in Gothic Literature series, incorporating other international multi-disciplinary works, with upcoming titles focusing upon national and regional Gothic. The volume adopts a comparative, cross medial approach, where each chapter has a ‘hub’ text forming a central core used to develop thematic textual analysis. In chapter one, ‘Dark Romance and du Maurier’s Gothic Kernow’, Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel (1951) is explored at the emergence of Cornish Gothic. The chapter argues that du Maurier’s work presents an animistic image of “Cornwall as a place of uncanny doubleness and as a space which can deceive, haunt, and echo its own imaginings” (p8). Discussion moves on to the film Bait (2019), which explores the division between the gritty reality of a working Cornish fishing village and the idyllic tourist vision of Cornwall. Chapter two, ‘Supersensory Gothic Kernow: Magic, Mysticism and The Esoteric Aesthetics of Emergence’, develops the idea of an animistic landscape by examining the occult artistic practices of Ithell Colquhoun and artists working within her legacy. Krzywinska and Heholt demonstrate that Colquhoun’s practice moved beyond “simple anthropomorphism”, instead generating the “mystical Gothic”, with an “imagination fully open to the stars and generative forces” (p39). Colquhoun’s deeply personal and spiritual understanding of the Gothic landscape, developed through magical practice, generated Surrealistic work showing unseen forces through line and colour. In the final chapter, ‘Strange Folk: Folk Horror Cultures, Ritual, and Witching Women’, David Pinner’s novel Ritual (1967), which inspired cult film The Wicker Man (1973), is used to trace Folk Horror’s Cornish roots. The authors explore how Cornwall, through Victorian folklore theory and liminal geography, has become reimagined as a site of pre-Christian, pagan ritual. In turn Cornwall has become a site of dark tourism, with local folk festivals reflecting Folk Horror themes. The concluding discussion focusses upon witching women and sea rites, to reveal a landscape that is also plentiful and life affirming.

Cornwall is a liminal peninsula, in England, but not quite English. It is part of the Celtic fringe, threatening to bring in ancient terrors from the margins (p14). The focus on the regional leads to an uncomfortable feeling of decentralisation, a disorientation. Krzywinska and Heholt argue that “Cornwall has a culturally acquired liminality, becoming a space of ambivalence, absence, excess, and loss” (p5). Cornwall has an “outsider-rebel identity”; its “uncanny light” makes it the home of artists (p6). It is a place where people move to escape busy lives, even just for a holiday. One of the most pertinent discussions in the volume considers the film Bait (2019), where two colliding conceptions of Cornwall, the tourist construction and hardships of the traditional fishing industry, clash. This generates a structural opposition in the text. The film is “filled with hints of uncanny and the supernatural” (p28), which are accentuated by the scratchy, imperfect black and white filming techniques, with elements of montage editing. In the film the Cornish fisherman is seen to represent the temporally ancient, a member of the folk being driven to the margins by modernity. Krzywinska and Heholt argue that “incomers impose a centrist/tourist romanticised re-creation of the past and the present, bringing in a version of Cornwall and its industrial past that threatens to obliterate both” (p29). This tourist vision threatens to overwhelm the traditional industry still clinging on. It is from this marginal perspective, Krzywinska and Heholt argue, that Cornish Gothic, with added magical elements, helped to birth the Folk Horror genre. The volume successfully establishes the “constitutional role” that the region has played in the development of key Folk Horror tropes (p51). Pinner’s novel Ritual is set in liminal Cornwall, not on the remote Scottish island of The Wicker Man. Both the film and the novel employ ritual imagery drawing upon deep roots. Roman writer Tacitus described the barbarity of the northern pagan rituals. In nineteenth-century folklore theory, pagan folk practice was considered to linger in marginal places, distanced from the ‘civilised’ intellectual centre of London. For folklorists, such as James Frazer, folk festivals and calendar customs were the surviving remnants of ancient fertility rituals. This survivalist theory echoes into the twenty-first century, adopted by the Folk Horror genre. Folk practices and rituals also became reanimated by enthusiasts, Folklore Society members, and modern pagans, such as Gerald Gardner. Cornwall has become, in literary fiction, film, artwork, and also occultist counterculture, a “place of light and nature from which to escape received norms and expectations” (p58). It is the home of the Boscastle Museum of Witchcraft and Magic, pre-historic stone structures, and folk festivals, such as the Padstow ‘Obby ‘Oss; all of which leverage dark tourism. Krzywinska and Heholt argue that “festive rituals active in Cornwall today hover between tradition and fiction”, their enactment bridges a gap between “the real and the fantastic” (p55). The contemporary dark tourism and folk festivals of Cornwall, such as the Halloween Dark Gathering at Boscastle, whilst sitting outside the focus of this volume, undoubtedly deserve far greater exploration. Gothic Kernow presents the opportunity for further interrogation of the structural connections between folklore, Folk Horror, and the Gothic in a regional context. Krzywinska and Heholt point out that that the Gothic is “rather thinly explored” in academic literature discussing The Wicker Man (p50). They are entirely correct to situate Ritual as a nodal text, sitting at the juncture of this fascinating cultural web. All those studying the Gothic, including a wider audience of du Maurier and horror film scholars, will have an interest in this volume. It is rich with analysis, considers an abundance of texts, and employs sumptuous descriptive language. This writing style itself replicates the excess of the Gothic genre, which is a joy to the reader. As a specialist volume, it concentrates on analysis, rather than outlining summaries. At eighty-two pages, the text presents a dense plethora of ideas and whets the appetite for future discussions. It highlights the importance of the interface between Folk-Horror and the Gothic. Opportunities for future conversations regarding the Neo-Pagan community’s connection to Gothic in the region are also elicited. This volume offers tantalising discussion of wider topics from a regional perspective. Perhaps the most important aspect highlighted is the emotional connection we experience towards our landscape through creative engagement. Gothic Kernow helps the reader understand the uncanny and uneasy human relationship with nature and the wild landscape; the estrangement we experience from an animist otherworld in a time of climate change, when we fear our future in the natural environment. The book underlines the prescient need to “regain a life-enhancing sense of connection with place, its Genius Loci” (p73). In this respect, the final section examines how ritual attempts to control nature, seeking to ensure plentiful harvests from land and sea. Ritual acts conjure hopes of “bounty and a conception of the Other as life-affirming” (p70). Through creative practice we can listen to the landscape and forge a deep understanding, giving animistic voice to the rocks, invoking the spirit of place. With such affection, a sense of protection will undoubtedly be forged.

Krzywinska, Tanya and Heholt, Ruth. Gothic Kernow: Cornwall as Strange Fiction (2022) is published by Anthem Press. |

|

|