|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | archive |

|

Waving or Drowning: Hilton’s Oi Yoi Yoi revisited

Steven Cousins explores the complex origins of Roger Hilton's most famous painting, and discovers a possible link to the younger St Ives artist, Tony Shiels.

The much loved and greatly admired ‘Oi Yoi Yoi’ by Roger Hilton is cited as one of the highpoints of the St Ives modernism created by the ‘second generation’ painters. It is hailed as a talisman of 60s liberation and wild body abandon. It is also a very good painting with innovations in technique as well as containing echoes of key works in European modern art such as Picasso’s The three dancers (1925), Matisse’s dancers and it is said, the colours of Mondrian. Strangely this emphasis on the painting’s probable European roots, its title, and the fact that he was at the time living and painting in London about an event said to have occurred in summer 62 or 63 in France, all distance it from a direct connection to St Ives.

Yet we will see there was a strong St Ives link which is reviewed here. The link is found in Hilton’s ‘leaping’ pose. This pose is one which is also uncharacteristically energetic for the women he created on canvas who, though very interesting, are rather more firmly held down by gravity. So there is a bit of a mystery here which we will explore.

An exceptional painting

For Hilton OYY was a triumph which he included in his material for the 1964 Venice Biennale. But it was also an exception. He is credited with seldom, if ever, painting more than one version of a similar image. The exception is this work and its sister canvas, Dancing Woman with both paintings realised in December 1963. A further exception is the sheer energy and dynamism contained in figures themselves. Both paintings offer a very positive, if explicit, female image. I can think of no other work by Hilton that celebrates women in such a life-enhancing way. Instead his other women are crushed to the ground or upended, or entangled with limbs, or made lumpen with massive body parts. If they were at sea they would be drowning! OYY and DW are exceptional for Hilton and I would argue for that reason are massively more popular with a wide range of exhibition goers than his other nudes. If works that are an exception to the artist’s normal imagery have become renown and so raised in the St Ives second generation canon, then that’s really odd. It needs some explanation, so here goes...

For a painter as good as Hilton, to be best known for something that is atypical is odd indeed. Defenders of OYY can point to the typical Hilton technique with which the painting is created. I have no disagreement with that; the drawing on bare canvas and over paint, the unpainted canvas figure surrounded by slabs of single colour are recognisably Hilton. It is not the technique that is atypical, but neither is the technique the thing that the wider public celebrates in this picture, it is the imagery. And it is the imagery that is atypical; the celebratory dynamic female figure. She is one of the female ‘wavers’ in this world – it’s just not Hilton’s bag. So how can it be? What explanation can there be for this picture? Surely his ‘best known’ work has to be deeply rooted in his core vision as a major artist. In reality I think it is, but only with an interpretation that is very different from its face value and easy viewing that has created such a positive response from the public. There are some good clues in certain of Hilton’s other paintings and drawings as well as photographs taken at the time. Together I think they provide the explanation and indeed locate the work firmly in his more traditional style as well as linking it more closely to St Ives.

I love Hilton’s work. It may not seem it from the above, but I do, and particularly his 50’s and 60’s abstracts, their amorphous forms and wonderful colours; Hilton as colourist. His struggle with a return to the figure from abstraction interests me intellectually. The packaging of him as an art commodity or feature of the art landscape that has occurred after his death, intrigues me as brand 'Hilton' gets appropriated and extended. He is now a key St Ives artist who painted dynamic figures, his objectionable behaviour and self-destructive drinking habits, a national treasure. Authors write, publishers publish and galleries exhibit of his posthumous success. For all his fame and brilliance at the time he died in relative poverty near St Just in 1975, in a room that was scarcely an Eagles Nest.

Origins & holidays

A mythology has developed around these two paintings. The story of OYY is that it is a Yiddish utterance made by his wife Rose leaping around naked whilst a haystack burned in the background during a holiday in France in 62 or 63. The pictures were painted in late 63 in London in colours the recent Hilton Tate show connected to the Dutch painter Mondrian. This geography again looks slightly odd for a work that has become an icon of the St Ives school located at south western extremity of the UK. It also shows that by 1962 the Hiltons were taking their holidays in France rather than St Ives area where Hilton had previously spent a few summers. It is on these summer breaks that rest his St Ives school status (together with some correspondence with St Ives artists). Then again who hasn’t taken a summer break in Cornwall? Hilton himself vigorously denied membership of such a parochial or regional ‘club’ compared to the metropolitan scene or being associated with major movements of European art. When he did finally move to Penwith in 1965 it is ironic that the works that most typify his later life – are clearly based on his earlier experience of the CoBrA group artists (Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam) again, scarcely spatially specific to St Ives in terms influence of that genius rural locus.

Reinterpreting OYY

The work that most clearly relates to OYY is Figure 1961. As Stephens (ref 1) points out, Figure 1961 is the first overt figure Hilton had painted for several years. This shows the same set of techniques found in OYY: the figure formed by painting around the edge of the canvas to leave the subject to be defined from blank canvas aided with charcoal lines, marks and smudges. The bunching and compression of the figure to fit in the box of the canvas is overt. The figure is also ‘turned on its side’ and has a great sense of imbalance and contortion. This, Stephens remarks, is so different to OYY, which is free dynamic and bouncing. We will come back to that comparison.

If this picture has indeed been ‘tipped over’ then let’s examine it in both of its alignments. In the official view we see a body supported on its knee and arm; its rear parts well in the air, which is something Hilton rather liked, and some vertical background bands in blue, then grey then black. The overall effect is somewhat voyeuristic, even misogynistic. When we rotate the canvas we get a very different interpretation.

The figure is logical, is balanced, we have foreground (black) mid ground (grey) sky (blue). The pose is big bottom centric and possibly a bit scatological. But this is a girl sitting on her haunches exhibiting a certain humanity and charm. I would not call this at all misogynistic.

So rotation through 90 degrees makes a big difference; it quite literally creates an imbalance, and massively changes the reading of the picture. Comparing Figure 1961 to OYY and DW Stephens says:

Unlike that from 1961, which is turned on her side and so confined by the canvas that her head has been distorted, here the women seem to dance in freedom and defiance. Undoubtedly they are shown as objects of erotic fantasy and desire but that does not mean they are simply passive. This is, it might be suggested, the new confident, open body of the 1960s.

This brief paragraph contains all the basic elements that give OYY its recognised importance and place in the art cannon. However apart from the last sentence the rest of the analysis falls on the first two letters of the paragraph. It is not unlike but like Figure 1961; OYY is a rotation through 90 degrees. This rotation does the opposite of what it did for Figure 1961, it takes a static and possibly misogynistic contortion and rotates it to provide a ‘dance in freedom and defiance’. However this comes at the expense of a passive and possibly restrained female of Hilton’s un-rotated and unreconstructed pre-60’s world.

Show me the evidence

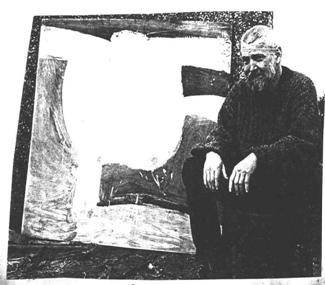

In a Roger Mayne photograph showing Hilton in his studio, he is painting a canvas on the floor. As you walk round such a piece it is not easy to see where is ‘top’ or ‘bottom’ particularly if the work is an amorphous plastic abstract. Painting on the floor must allow a greater freedom to explore where is ‘top’, and may have left him with a greater flexibility in this regard. All that we think know for sure is that the most closely related painting to OYY/DW was rotated through 90 degrees to give it a radically different impact when hung. Hilton is quoted as saying that Figure 1961 ‘this is going to shock the troops’ when shown at Waddington's in January 1962. I can’t believe that the un-rotated picture would have had the same shock value. So the lesson is that rotations can sometimes work wonders.

When OYY or DW are rotated back through 90 degrees the self-same logical resolution of the figure occurs that did so in Figure 1961. Instead of imbalance and motion we see balance and a heavy stasis. We see a logically grounded woman kneeling on one knee and resting her body with one extended hand, the naked body broken over the edge of a bed with the other leg and the arm reaching back, possibly even tied. The breasts now are totally logical, one fallen, the other resting on the chest looking smaller when side-on to the viewer. Just as in Figure 1961 the vertical bands of colour gave clues to the horizontal in rotation, so too here with the vertical colour breaks in front of the head and around the lower foreleg which read across to the floor and bed edge or pillow in the rotation. It is ironic that the area between the knee and forearm in Figure 1961 is in-filled with a flat blue ground up to and gently holding the breast. The same device is seen is in OYY/DW when they are rotated. However this blue ground in the latter two cases has been interpreted as a savage hand grabbing at the entire breast. This is the only previous comment to suggest a slightly darker reading of both pictures.

In Picasso’s The three dancers (1925) it is not gravity but the centrifugal force of a wild spinning dance that achieves the same effect as OYY and where the breasts have dynamics that genuinely defy the effect of gravity. OYY is classic Hilton; when rotated through 90 degrees, the body loaded and brought down by gravity, heavy, stationary, explicit, misogynistic, brutal. I say brutal because having tried out this position with a clothed volunteer; it is back-braking. It opens the body up, yes, but is definitely brutal. Try it.

Two further pictures can also shed light on this interpretation plus one of the later night letter drawings.

A key component of the otherwise dynamic OYY in its conventional hanging is the vertical colour break in front of the head which halts the head’s movement while all else flies on. In rotation this break is of course horizontal, something to rest the head upon. We see this same horizontal form in a slightly earlier painting. The figurative painting Figure February 1962 where the head, like OYY, is in the centre of the picture edge and shows the head resting against the colour break. This very similar device reinforces the view that OYY has been rotated 90 degrees. It also shows that his taste in women was definitely more horizontal and indulgent, and less than celebratory or feminist. Figure February 1962 is an ambiguous picture which can be read in several ways. For our purpose of exploring OYY it is important that the head and neck of the most obvious reading of the figure is resting on the ground fringed by a blue sea or blue pillow on the left edge of the canvas. But Hilton is also trying to trick the viewer. Trickery is not an unusual trait in some artists’ craft or love-hate relationship with their viewers. Stephens has elegantly stated that artists such as Hilton can deliberately create images that can be read in several ways ‘That ambiguity is surely the point’ (ref 1). Figure February 1962 has the colour of ordure, and in one ambiguous reading shows not a head and neck but the male member in the act of sodomy. Two characteristically raised female rears in the manner of Figure 1961 and the graphic excremental penetration of one leading to a seminal off-white area in the figure’s abdomen. Another reading of this picture gives a person supported on arms and legs from the knee. This format also reads across to OYY in its rational rotated form where she is on her hand and knee. For all its dark content Figure February 1962 is a very powerful picture and I thought gave OYY a real run for its money when shown together at the 2006 Hilton show at Tate St Ives.

My inference is that Figure February 1962 and OYY/DW are closely related in structure but also in spirit. I have also added a 1965 pastel drawing which echoes the rising buttock and sagging breast along with an explicit cane and voyeuristically beaten female rear end. Within these three images we see Hilton’s interest in the pendulous sagging breast or sagging stomach; his interest in welts from caning with perhaps similar welt marks over the Dancing Woman who also seems to have in addition an actual or potential mastectomy a la Amazon warrior. The high -omed buttocks read across all of the pictures considered here including OYY/DW in rotation.

The main feature and the reality of the pose of OYY/DW is the back-breaking contortion of falling off a bed supported by one arm and knee – consistent with Hilton’s rational poses this requires a balancing force to hold the body from collapsing onto the floor – which is provided by what appears as ropes to the right arm. This image is of someone exhausted by whatever has gone on and slumping off the bed to the floor still held on one arm by ropes, with sagging breast and thigh, hair falling forward. This is a woman who is definitely less waving and a lot more drowning.

Lightening the subject a little we are also treated to knowing that Hilton liked cotton underwear (on his ladies). Here the underwear wearer is in the pose that would appear running if rotated but is static and exposed on the page. She is supported by two arms and the knee. Either nothing, or, it’s a hark back some nine years later at end of his life to the OYY pose of his most famous painting.

Why did Hilton rotate Oi-Yoi Yoi for final hanging?

I have made the case that OYY like Figure 1961 is a rotation of rationally posed picture that was in its un-rotated form totally consistent with Hilton’s normal gravity-laden imagery. So the question then, is why would he do this? Why would he change the habit of a lifetime; why take a ravaged slumped female and rotate her into such a dynamic positive female image? Why do this twice? Why rotate that picture when the outcome is so out of character with practically everything that he had done before or since? Why have scholars built such an edifice around Hilton’s ‘dynamic figuration’ from this pair of atypical paintings?

The first answer may have to do with ambiguity. He is apparently saying one thing – all commendable 60s exuberance, innocence and light – but meaning another. Codding his audience, enjoying the fun of the trick and the alternative reading. To use the quote from Stephens again ‘That ambiguity is surely the point’ in certain aspects of painting. But this is just part of an explanation of OYY and insufficient in total. The leaping pose caught by the Snowdon photograph shows other sources of inspiration for the picture that are closer to the 60’s zeitgeist. The source of Hilton’s leaping pose is a more interesting question. So the second answer is more to do with what others were doing at the time and the need for Hilton to stay ahead in an area, new figuration, that he had made his own cause.

Hilton has a record of ‘borrowing’ from other painters that exceeds any other prominent artist I have come across. This is a respectable thing to do, you have to build on what is gone before and here we just note that he does it, extensively. It is perhaps key to understanding him as a painter, his progression and the regular re-invention of his style. Hilton’s Grey Figure (1957) had been praised by Patrick Heron (ref 2) as a ground-breaking figurative masterpiece, mentioning that painting’s debt to Picasso. Its similarity to the seated figure in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon does indeed look convincing. Hilton has been credited with ‘drawing upon’ Picasso on other occasions (Picasso-like Heads) but more widely, Bissiere, Manessier, Poliakoff, Mondrian, Constant, CoBrA, and no doubt others have been chosen.

From St Ives, Frost and Heron have been imitated by Hilton. Adrian Lewis also mentions Hilton ‘coming close’ to William Scott (left above, Hilton right) who Hilton thought was “the greatest artist I know”. Lewis also mentions Bryan Wynter as a style for some of Hilton’s works; Stephens suggests the photographer Bill Brandt. Here I add the young painter Tony Shiels as a stimulus. Shiels too was wrestling with abstraction, landscape (seascape) and the figure when Hilton encountered him. Taking substantial inspiration from other painters appears to have fed Hilton’s evolution as a painter, fed his competitive spirit and his drive to surpass other painters to be constantly at the ‘leading edge’.

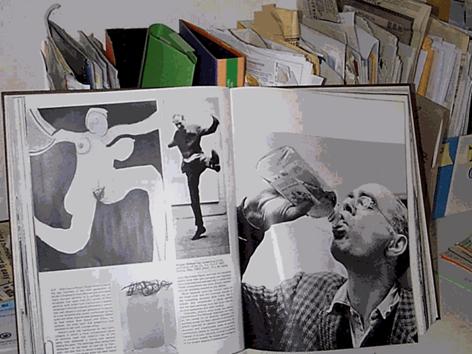

The leaping pose

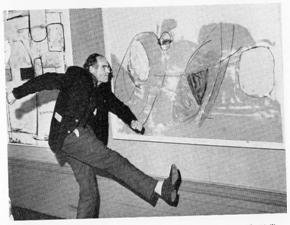

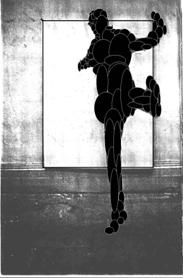

This leaping pose (left above) is graphically linked to OYY as we see on the page of the open copy of Lord Snowdon’s book Personal View 1979 which heads this essay. The same link is made at length by Adrian Lewis (ref 3). In addition Lewis conjectures that the photograph of Hilton at the infamous Liverpool John Moore's award (right above) also shows preparatory thinking for OYY. Both photographs were taken in second half of November '63 and OYY completed in December 63. The John Moore's event (photo) was on the 13th November 1963 and Lord Snowdon’s photograph the 21st November 1963. The Snowdon picture finds that behind the leaping Roger is a drawing on the canvas that is very simple and preparatory but clearly related to OYY. So like Lewis, Snowdon and others, this pose is seen as critical to the construction of OYY and DW and is indeed dynamic and a major move on from Hilton’s previous figurative work in terms of depicting female energy. If Figure 1961 was his first overt figure for many years, the closely related OYY was his first ever dynamic figure. This leaping pose however was not original to Hilton but a characteristic pose of dynamic nudes by a then young St Ives-based artist, Tony Shiels.

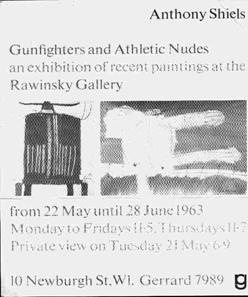

Hilton’s pose is an exact enactment of the signature pose of nudes painted by Tony Shiels. In the two years before December 1963 Shiels produced at least 100 versions of this pose including large scale works which were known to Hilton both by his visit to Shiels’ studio in St Ives and by his exhibitions in London at the Rawinsky gallery summer 62 and 63 just off Carnaby Street at the heart of swinging London. I once received a letter from Michael Canney, former director of the Newlyn Orion gallery, in which he wrote that Shiels could not possibly have influenced Hilton because he, Hilton, was only influenced by great artists. So turning this on its head, was Shiels a great artist, or phrasing it differently, did he have sufficient credibility in 1963 for Hilton to have seen something significant in what he was creating at the time, particularly for the figure? The answer is clearly yes. Great play is made in Andrew Lambirth’s book (ref 2) that Hilton had a highly prestigious show at the Galerie Charles Lienhard in Zurich in 1961 for which Alan Bowness wrote a brief catalogue introduction where he concluded:

The work of the best painters of the mid-twentieth century (and I include Hilton among them) can have just the same sort of power and significance that the great painting of the past has possessed.

Having anointed Hilton in this fashion, Bowness’ catalogue introduction a year later for Shiels’ London show at the Rawinsky would have given his work, especially the figures, a certain credibility:

I first noticed Anthony Shiels’ paintings in a small St Ives gallery some two summers ago. They owed much to other painters working in Cornwall – Peter Lanyon in particular – but this isn’t surprising (or discreditable) in a young artist’s work. In any case, the pictures, mostly small gouaches with landscape subjects, had a distinct quality of their own – they were done by someone with a natural ability to make interesting pictorial compositions and a real feeling for paint and colour. Shiels has continued to develop. His recent oils have been mostly of the figure, an image both generalised and particular, as the landscapes were. The nudes are more ambitious and personal, and perhaps less completely successful, but they have the same painterly freedom and ease that distinguished the earlier work. Anthony Shiels is a painter to watch. May 1962.

Shiels next show at the Rawinsky in 1963, Gunfighters and Athletic Nudes, took his figures on further. The show was favourably reviewed in Apollo magazine. Earlier in 1961 Shiels had been photographed along with ‘names’ Heron, Hepworth, Lanyon, Mitchell, Frost, Wynter, Lowndes, Leach, in the Ida Kar photo journalism piece Le Quartier St Ives in The Tatler. So we can safely say that he was a young but visible player in the early sixties art scene in St Ives and to some extent in London too. Key to his relevance to Hilton though was his dynamic, energetic and innovative work based on the human figure. He had enough artistic status at the time to influence Hilton if Hilton was up to his old tricks of borrowing and building upon visual ideas of others.

I have made the case that like the very closely related painting Figure 1961, OYY is a rotation of a stationary figure and that Hilton’s leaping pose is a direct reference to Shiels' dynamic figures of the time. This interpretation is at odds with Adrian Lewis’ emphasis on the importance of the Hilton pose when as we know it is actually a Shielsian pose. We may therefore lend across to Shiels the cultural lightening rod that is described here. Lewis goes to town on the relevance of the Snowdon photograph which is now at odds with the above evidence although it shows Hilton appreciated the importance of the pose.

On the one level, the Snowdon photograph of Hilton dancing reflects a type of image which had recently emerged in the artist’s work (sic). More generally, it might hint that Hilton’s painting itself is organised around generating pictorial energy. Broader and longer-term perspectives show that such imagery relates especially to the motif of dance in late nineteenth- and early twentieth–century art, from Rodin to Matisse, in which the energies of consciousness and body seem conjoined. From the late 1940’s Hilton had been taken with the image of dance…. ‘What shall [the painter] represent? … The elements of a dance but where people and things are as yet unidentified – the dance of the future which we hope for but which is not yet here.

This links Hilton to a tradition of utopian thought, particularly strong in nineteenth-century anarchism and socialism, in which the dream of a future ideal society is encapsulated in a vision of communal dance. By contrast with his post-war vision, an older Hilton in the Snowdon photograph engages in a solitary dance, discovering joy inwardly.

David Mellor has described a rash of images of ‘clownish, unstable, leaping, open bodies that erupted into the iconography of the early Sixties’ which he attributes to the end of certain industrial routines and attendant social controls. However, analysing such images demands that we see differences in stance as well as similarities. Hilton’s own image (sic), however self-conscious, seems addressed to the viewer far less than many contemporary prancing images from the hormonally-charged youth culture of the time. Hilton seems by contrast in his own world, expressing what Norman Brown called ‘body mysticism’, in which consciousness ‘does not observe the limit, but overflows’. Such Dionysian consciousness, for Brown, delighted ‘in that full life of all the body which it now fears.

The Dionysian spirit had been discussed by Friedrich Nietzsche, a favourite author of this generation, in The Birth of Tragedy (1872). In this text, we find the celebration of self-oblivion in excess, a yearning for a primal unity, an image of the satyr as ‘one who proclaims wisdom from the very heart of nature’, all themes to which Hilton would have warmed. The acrobatic connotations of Hilton’s body-motif (sic) also recall Nietzsche’s images in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-5), those of tightrope-walking across an abyss or of learning to fly to ‘kill the Spirit of Gravity’. All such images in Nietzsche relate to the individual’s potential for self-sufficient joy. The image which Snowdon’s photograph of Hilton presents is one of primal energy which cannot be suppressed by means-ends rationalisation, by the tailoring of the body to useful productive ends (ref 3).

Hilton ‘kills the Spirit of Gravity’ by rotation and sarcasm rather than any deeper reference to European culture. He is not killing but wallowing in gravity in the body of his work; getting his nudes to the horizontal seems key. Whereas, from what I know of the other artist, Shiels fits the ‘hormonally-charged youth culture of the time’ and the ‘unstable, leaping open bodies’ of David Mellor. In passing, the Snowdon photograph is taken at the time the work OYY was in progress, which is what makes the connection with Shiels so interesting rather than as suggested above to be after it was completed.

Exhibitionism

It is perhaps necessary to link OYY to St Ives if only to justify its frequent showing at St Ives Tate and it’s prominence in St Ives related literature.

So does it matter ‘who did what, when and why’? Probably not at one level. OYY is a good painting and worth seeing anywhere. However, a picture is so feted in the St Ives canon needs to be grounded securely there, or it’s a plus at least, if it can be. Shiels’ work does this. Without it we are left with a few letters from London to Terry Frost either side of a period of some 4 summers in late 50’s when Hilton had a studio in the area linked to his vacations (ref 3) and this important Hilton scholar strongly questioning the link.

Visual clues

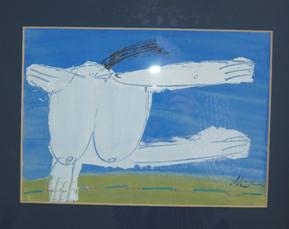

We can see common themes present in OYY and some of Shiels’ works, other than his one-leg balanced leaping nudes.

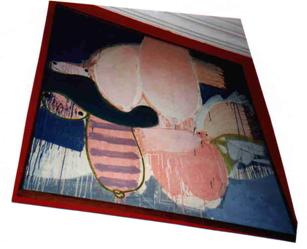

Shiels’ Nude on Yellow circa 1961 – oil on board 36”x 36” (left, above) was the one illustration in his 1962 Rawinsky exhibition catalogue with the Bowness commentary. It shows a woman laying with one breast pointing down and the other face-on, which is the primary image structure of OYY. This picture is now lost. The torso is boxed by the board as much as Hilton’s Figure 1961 but somehow it is positive and without insult, for all its lurking male member companion. A monotype from the 1963 Rawinsky exhibition (above, right) shows a vitality of treatment of the female form, and the arms exploding into the top corner of the picture as several of his figures did including gunfighters (see Gunfighters and Athletic Nudes catalogue cover, above).

The third picture* 1963 approximately 48” by 48” is of four witches flying through the sky exposing massive bomb-like breasts. One bosom is horizontally striped, which Shiels says is a reference to Picasso’s jumper, while he links the picture as a whole to Robert Goodnough’s painting relating to the ‘Bay of pigs’ invasion of Cuba in 1961. I call this Shiels’ Guernica. *full quality image of this work will be posted shortly.

Finally this picture is of a nude 1963 on one leg and is approximately 60” by 60”.

These last four works are part of a quite large body of Shiels’ work of genuinely dynamic expressive, exuberant nudes coming from St Ives from 1960 and being shown in London in late spring early summers of 1962 and 1963.

It is my contention that this new figurative work challenged the leadership that Hilton had established earlier in his quest to move from abstraction to the figure. By adopting his technique of ‘borrowing from’ and improving upon the work of others he considered relevant we see Hilton going beyond what he had previously reached in his treatment of the human figure. The paradox of rotating his canvas allowed him to stay true to his core vision and arguably misogynistic treatment of the female nude while at the same time creating a new dynamism which upstaged any would be competition and shows him superficially joining the 60’s revolution.

Conclusion

The only casualty in Hilton’s cleverness is truth. Art can be whatever it wants to be, but the big cultural currents that Lewis and others ascribe to significant painters such as Hilton need to hold reasonably true. Being clever with ambiguous images is fine but this is based on sarcasm rather than building the new post-war Jerusalem. Having established that OYY and DW are drowning rather than waving I find I retreat to Hilton’s earlier abstracts and to where he begins his journey with the figure. These seem totally honest, exciting and beautiful images. OYY and DW now feel overly contrived and I prefer the figurative works by the new painters of the early Sixties, such as Tony Shiels, whose spirit is authentic to that decade (ref 4). When Alan Bowness said Tony Shiels should be 'watched' I think he was proved right' and indeed he can still be watched as he is one of the few artists working in the peak period 57-64 in St Ives who are still painting today.

Recent works by Tony Shiels are on show at the Fernlea Gallery, St Ives all August and September 2014.

References

1 Chris Stephens (2006) Into Seeing New – The Art of Roger Hilton 2 Andrew Lambirth (2007) Roger Hilton – The Figured language of Thought 3 Adrian Lewis (2003) Roger Hilton 4 Steven Cousins (1995) Tony Shiels

Note: Tony Shiels first drew my attention the rotation in OYY. All other observations are the authors own.

|

|

|