|

Medea’s charms: the writings of

Ithell Colquhoun

Ithell Colquhoun (photograph below left by Man Ray) is best known as a

Surrealist artist. Her occult-infused novel, 'I Saw Water', unavailable

during her lifetime, has now been published by Pennsylvania State

University. Richard

Shillitoe who co-edited the text, describes the book and its context.

Ithell

Colquhoun (1906-1988) was a highly original creative force who expressed

herself through painting, collage, poetry, novels, short stories and

topographical books. This diversity was bound together by an animistic

view of the universe in which, in some mystical sense, all matter is

alive and interconnected. It is a refrain that runs through all her

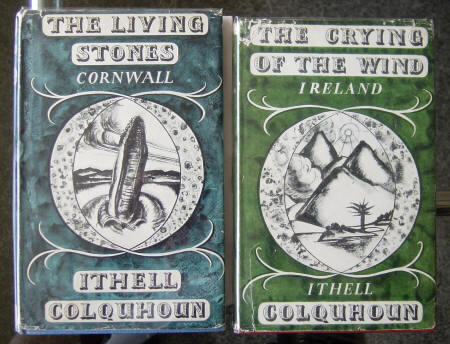

work, being especially evident in her best known book, The Living

Stones: Cornwall (1958). It is contained within the title itself,

just as it is in the title of her earlier book on Ireland, The Crying

of the Wind (1956). In her world, both literal and metaphorical,

stones live and the wind cries. Ithell

Colquhoun (1906-1988) was a highly original creative force who expressed

herself through painting, collage, poetry, novels, short stories and

topographical books. This diversity was bound together by an animistic

view of the universe in which, in some mystical sense, all matter is

alive and interconnected. It is a refrain that runs through all her

work, being especially evident in her best known book, The Living

Stones: Cornwall (1958). It is contained within the title itself,

just as it is in the title of her earlier book on Ireland, The Crying

of the Wind (1956). In her world, both literal and metaphorical,

stones live and the wind cries.

Colquhoun was drawn to Cornwall as a place where spiritual and earth

forces are constantly revealed through standing stone, holy well and

natural rock formation. She spent much time in trying to engage with

these natural forces through divination, meditation and the study of

occult theory. Her association with the Land’s End Peninsula,

established during childhood holidays, was resumed during frequent trips

to escape from wartime London. In 1949 she purchased a rudimentary

tin-roofed wooden studio in the Lamorna Valley which she named Vow Cave.

This was uninhabitable during winter, but in 1959 she was able to buy

Polgreen Cottage in Paul (later renaming it Stone Cross Cottage) and saw

no need for further relocations. She lived there until her death in

1988. Much of her writing was done in Cornwall and much of it reflects

its ambience. Her literary talents, however, had already been evident

for many years, initially finding expression in the essay format.

Essays Essays

One constantly present theme in her essays is the magical. It was

displayed in her first publication, The Prose of Alchemy (1930),

a lengthy essay that celebrates the rich poetic imagery found in many of

the classical alchemical texts of previous centuries. It was written

whilst she was a student at the Slade School of Art and published in

G.R.S. Mead’s influential journal of Gnosticism and esotericism, The

Quest. Mead had been part of Helene Blavatsky’s inner circle in the

1880's but he had resigned following internal schisms within the

Theosophical Society and formed the Quest Society. Colquhoun’s essay was

later described by the poet David Gascoyne as “one of the best, most

stimulating, short introductions to the subject of alchemy considered as

imaginative literature that exists in English”.

A later essay The Mantic Stain (1949) was the first article to be

published in English on automatism, the method practiced extensively by

the surrealists (as well as many mediums) for finding inspiration in

apparently random blots, smudges and stains, into which they ‘read’

images or built narratives. In trying to get beyond conscious, rational

control, Colquhoun herself practiced many automatic methods for

generating images or word combinations and associations.

In another essay, The Night Side of Nature (1953), she attempted

to reconcile contemporary science and the apparently discredited old

world-view of the animists and the alchemists. She defended the

so-called pathetic fallacy, proposing that Man is subjected to the same

forces that impel the rest of nature. She drew parallels between human

psychology and natural phenomena, regarding, for example, the

‘splitting’ of the psyche as described by contemporary psychiatrists as

essentially the same process that splits rocks such as shale and slate.

Geoffrey Taylor, the literary editor of The Bell, the foremost Irish

literary periodical of the time, praised the lucidity of her writing and

described the essay as “elegant and ingenious – the most persuasive

account of the new astrology that I’ve seen”.

Other writings on esoteric themes range from the popular to the

recondite. The series of articles written for Prediction magazine were

intended for a general audience, whereas the essay in which she

speculated that women are more evolved than men because their bodies

contain more orifices must have been understood (or taken seriously) by

a much smaller audience!

Poetry and short stories

Throughout

her life she published poems, short stories and translations of French

poetry in literary magazines. She is well known for her links with the

surrealist group in London just before World War II, but it is rarely

appreciated that for a short period in the 1940s she was also associated

with the New Apocalypse writers. Largely forgotten today, The New

Apocalypse was a post-surrealist Romantic movement whose leading lights,

the poets Henry Treece and Jim Hendry, thought highly of her work,

especially the psychological insights shown in her short stories. They

planned to include her work in Apocalyptic anthologies. However, the war

and personal animosities put paid to their collaborations. In fact this

was Colquhoun’s constant fate; to be on the periphery of groups, seldom

fully accepted, sometimes expelled. Behind great personal charm she had

a steely determination and refusal to compromise that was off-putting to

many. Even today, despite being the most original of the British

surrealists, she has never been properly recognised by art or literary

critics, or by the general public who seldom have the opportunity to

view or read her work. Throughout

her life she published poems, short stories and translations of French

poetry in literary magazines. She is well known for her links with the

surrealist group in London just before World War II, but it is rarely

appreciated that for a short period in the 1940s she was also associated

with the New Apocalypse writers. Largely forgotten today, The New

Apocalypse was a post-surrealist Romantic movement whose leading lights,

the poets Henry Treece and Jim Hendry, thought highly of her work,

especially the psychological insights shown in her short stories. They

planned to include her work in Apocalyptic anthologies. However, the war

and personal animosities put paid to their collaborations. In fact this

was Colquhoun’s constant fate; to be on the periphery of groups, seldom

fully accepted, sometimes expelled. Behind great personal charm she had

a steely determination and refusal to compromise that was off-putting to

many. Even today, despite being the most original of the British

surrealists, she has never been properly recognised by art or literary

critics, or by the general public who seldom have the opportunity to

view or read her work.

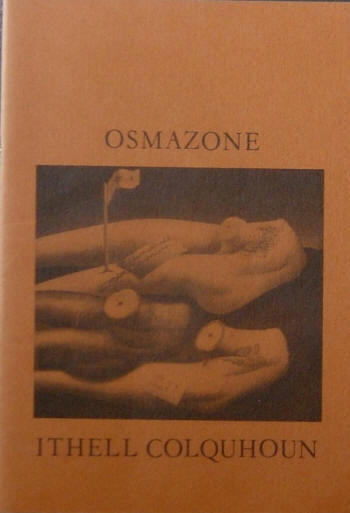

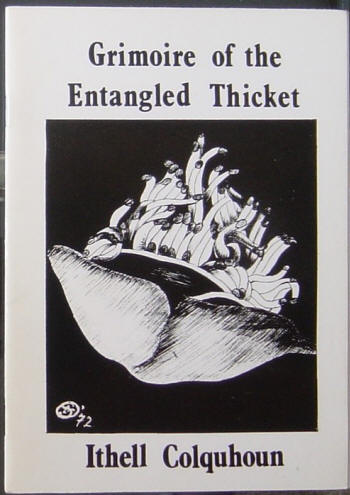

Two slender collections of poetry and prose writings were published

during her life: Grimoire of the Entangled Thicket (1973) and

Osmazone ten years later in 1983. Both were illustrated with her own

drawings. The eight poems in the Grimoire owe much to Robert Graves’

theorising about Celtic mythology and the White Goddess. They form part

of a series of twenty two poems – one each for the thirteen month Celtic

lunar calendar plus nine for the pagan festivals that mark the year’s

progression.

Osmazone is a strange but representative compilation that

includes both poems and short prose pieces. There is a poem about the

anus, a short story in which a woman applying for a position in a

modelling agency includes in her CV jobs in which she has modelled for

enemas and gynaecological examinations. A short autobiographical text

deals with her menarche, whilst a ‘found-object poem’ lists varieties of

condoms. There is a surrealist group-poem in which each participant

contributes a line in ignorance of what has gone before, whilst another

poem gives tonsorial advice to a member of a family of Breton

nationalists. It is a shame that it was published in such a small

edition (only 200 copies) and is very hard to find today.

Other

Writings Other

Writings

In addition to her two published travel books she wrote another, The

Blue Anoubis, based on a Nile journey undertaken in 1966, and also

illustrated with her own drawings. The book is raised above the level of

a travelogue by her regular and detailed comments on Egyptian gods and

godesses: “It is amusing”, she wrote, “to classify the deities of the

pantheon, according to their morphology, under the various zodiacal

signs”, before proceeding to tabulate their attributes. Maybe so, but

this must also have limited its appeal to any prospective publisher.

In 1968 she was asked by the editor to contribute a series of articles

on holiday destinations to The Times Educational Supplement. This she

did with gusto, in one instance offering readers unexpected information

regarding archangels.

Novels

Colquhoun’s first novel was Goose of Hermogenes, published in

1961 but written over twenty years previously. On the surface, it is

about the heroine’s relationship with her uncle who lives on his island

retreat and engages in esoteric experimentation, the ultimate aim of

which is to conquer death. The heroine undergoes trials involving

separation and purification. She discovers the transforming power of

sexual ecstasy. Through physical imprisonment and psychic probing, she

learns about possession, both physical and spiritual. Eventually, she

returns to her point of departure, to the house where her parents had

separated, and achieves reconciliation with her father, now dead.

It is, clearly, an allegory of the alchemists’ quest, whether it be

regarded as the elixir of life or spiritual purification. The context is

not merely alchemical, however, but contains Pagan and orthodox Catholic

strands whilst having much to say about Goddesses and gender

inequalities. Some passages are clearly derived from dreams, but as no

working drafts survive, her method of composition is not recorded. The

position is very different as far as I Saw Water is concerned

because she kept all the drafts and notes.

I Saw Water

It was Colquhoun’s life-long practice to record her night-time dreams.

Dreams were important to her both as a source of artistic inspiration

and of hidden, magical knowledge. During sleep, she would have argued,

rationality is at its weakest. Sleep, therefore, is the time when we are

closest to the gods and at our most receptive to godly messages – if we

can understand them. For her, artistic inspiration and magical knowledge

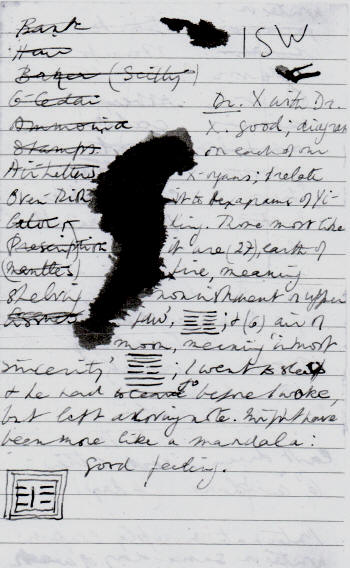

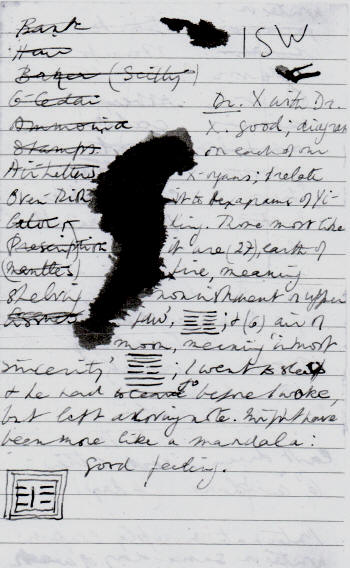

were one and the same. The illustration, of a notebook page from the

early 1950s (below right), shows just how art, literature, dream and

magic were integral to Colquhoun’s daily life.

There

is a shopping list on the left of the note, apparently anticipating a

trip to the Scilly Isles. The large ink blot in the middle serves as a

reminder that her visual art relied heavily on the interpretation of

chance forms generated through automatic processes. The dream summary on

the right hand side has been earmarked for possible inclusion in I

Saw Water. (The Dr. X of the dream was a Jungian psychotherapist

which whom Colquhoun, a patient of his for a spell, had a difficult

transference relationship.) The patterns of short horizontal lines form

some of the figures of the Yi-King (more commonly spelled I-Ching)

derived from an ancient method of divination and which Colquhoun

incorporated into the novel. There

is a shopping list on the left of the note, apparently anticipating a

trip to the Scilly Isles. The large ink blot in the middle serves as a

reminder that her visual art relied heavily on the interpretation of

chance forms generated through automatic processes. The dream summary on

the right hand side has been earmarked for possible inclusion in I

Saw Water. (The Dr. X of the dream was a Jungian psychotherapist

which whom Colquhoun, a patient of his for a spell, had a difficult

transference relationship.) The patterns of short horizontal lines form

some of the figures of the Yi-King (more commonly spelled I-Ching)

derived from an ancient method of divination and which Colquhoun

incorporated into the novel.

In about 1967 she began trawling through her dream diaries of the

previous two decades, selecting those that she felt were linked in some

way. She stitched them together, gave them a setting and a narrative

structure, and the result was I Saw Water.

It is set on the island of Ménec where Sister Brigid is a nun. The Order

she belongs to, the Sisters of the Parthenogenesis, is ostensibly Roman

Catholic, but its mission is more reminiscent of certain schools of

alchemy than of Catholicism: it is the unification of the separated

genders. The achievement of this will transmute fallen, sinful, humanity

to a state of spiritual perfection, restore nature’s equilibrium and

confirm the unity of the hermetic cosmos. In addition, many aspects of

conventual and ritual life on Ménec have more in common with Pagan

nature worship than with Christianity. Colquhoun also drew on her

knowledge as a practicing Druid. Ménec itself, it transpires, is the

Island of the Dead and all the inhabitants, nuns and laity alike, are in

transit, working their way towards their second death. The second death

is a teaching that is not found in Judeo-Christian theology but is

associated with Eastern belief systems. Colquhoun would have been

familiar with it through her membership of the Theosophical Society. A

major influence on Sister Brigid is the local landowner, a figure who is

surely to be identified with Adonis, the mythological vegetation god. He

entices Brigid from the convent, but dies (inevitably) by drowning.

Eventually, Brigid is able to cast off her personality and human

emotions and achieves a state of disembodied peace. The book is narrated

in a matter-of-fact style that recounts as commonplace a remarkable

series of events. Naturalistic passages are juxtaposed with lengthy

sequences, almost unaltered from the dream diaries, with resulting

dislocations of time, place and logic.

I Saw Water is published in a volume that includes an

introduction and end notes. It is supplemented with a full bibliography,

a number of poems, short texts and images, many also printed for the

first time, which place the novel in the broader context of Colquhoun’s

work. It is not light holiday reading and you will not find it at the

railway station bookstore or the airport news-stand. But, if you are at

all interested, seek it out. It is the first substantive piece of

Colquhoun’s writing to appear since her death. It will transform your

understanding of her and her life’s work.

publisher’s web site

http://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-06423-9.html

see also

http://www.ithellcolquhoun.co.uk/ |