|

Surrealism in Cornwall:

Pailthorpe & Mednikoff, Thomas, Tunnard & Colquhoun

Rupert White

In 1934, six years

after Ben Nicholson ‘discovered’ Alfred Wallis in St Ives, he and

Barbara Hepworth were married. By this time the power couple of British

Modernism, they became outspoken advocates of abstract art, which had

slowly begun to gain support amongst the cognoscenti in Britain. But

then, in the mid 1930's, abstraction was suddenly outflanked by a

different and more alluring alternative: Surrealism.

The term ‘Surrealism’ was first coined by the French poet Guillaume

Apollinaire, but it was given a more tangible identity, initially as a

literary movement, by poet Andre Breton who wrote its first manifesto in

1924. Adopting a bombastic tone, reminiscent of DH Lawrence and the

English Socialists, he denounces rationalism: 'Experience itself has

found itself increasingly circumscribed. It paces back and forth in a

cage from which it is more and more difficult to make it emerge. It too

leans for support on what is most immediately expedient, and it is

protected by the sentinels of common sense. Under the pretense of

civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind

everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy;

forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance

with accepted practices'.

Breton famously goes on to define Surrealism as: 'Pure psychic

automatism by whose means it is intended to express, verbally or in

writing, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought.

Dictation of thought, in the absence of all control by reason, and

outside of all aesthetic or moral preoccupations….Surrealism is based on

the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of association

hitherto neglected, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested

play of thought. It tends to ruin, once and for all, all other psychic

mechanisms, and to replace them in solving the main problems of life'.

Surrealism did not make much of an impact on British art until June

1936, however, when the International Surrealist Exhibition opened in

The New Burlington Galleries in London. The show had been initiated by

two Englishmen, poet David Gascoyne and painter Roland Penrose. The

British artist-contributors, of which there were 27, were selected by

Penrose and art-critic Herbert Read, and the continental by Breton and

Paul Eluard (Remy, 1999). Around 400 works were jammed together on the

walls of the gallery, and talks were given by artists including,

famously, Dali dressed in a deep-sea diver’s suit. (Harrison, 1981). The

exhibition attracted great publicity, though was received with hostility

by a conservative British press. Herbert Read, in his book ‘Surrealism’

(1937), gave a less reactionary view: June 1936: the International

Surrealist Exhibition broke over London electrifying the dry

intellectual atmosphere, stirring our sluggish minds to wonder,

enchantment and derision.

British artists had been rather slow to pick up on Surrealism. Neither

of Cornwall’s best-loved Surrealist artists, John Tunnard and Ithell

Colquhoun, for example, embraced surrealism until after the 1936

exhibition. In fact it is even doubtful that there were many true

Surrealists amongst the 27 British artists that were in the exhibition.

Most had simply adopted the look, without understanding or fully buying

into the philosophy.

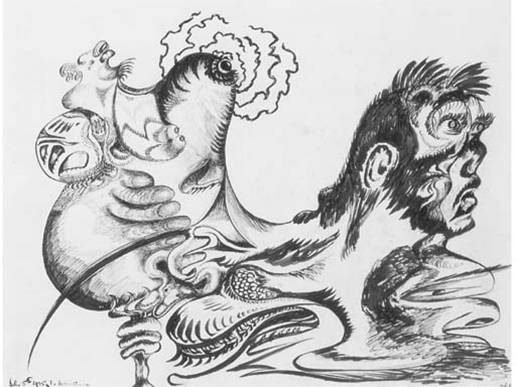

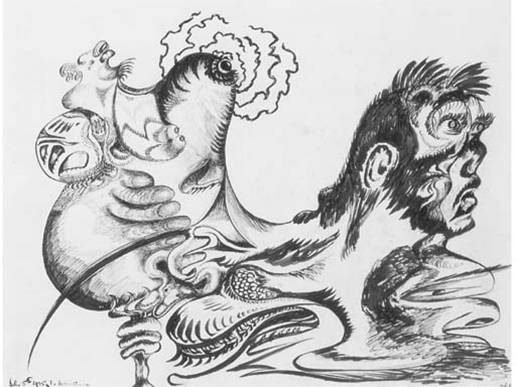

Ancestors l 1935 by Grace Pailthorpe. One of three

powerful automatist drawings Pailthorpe contributed to the International

Surrealist Exhibition. (Others were ‘Wind’ and ‘Ancestors ll’)

However, probably

because of their involvement with psychoanalysis and their unflinching

ideological commitment to psychic automatism, Breton later singled out

two of them: Grace Pailthorpe and Rueben Mednikoff. He regarded their

contribution as ‘the best and most truly Surrealist of the works

exhibited by the British artists’. Others have said that ‘they

were the haunting conscience of British Surrealism because they explored

the unconscious in the most thorough tenacious and uncompromising way’

(Remy, 1999).

Since May 1935, Pailthorpe and Mednikoff had been working in a modest

bungalow in Port Isaac, an isolated fishing village near Wadebridge a

few miles up the North Cornwall coast from DH Lawrence’s wartime getaway

in Porthcothan. Theirs was a rather strange relationship, to put it

mildly, and the art they produced even more so.

Pailthorpe was a surgeon, turned psychoanalyst, who had received

prolonged Freudian analysis from Dr Ernest Jones; later Freud’s

biographer. Although she was subsequently scathing of the experience,

she went on to publish research on delinquency that led to the

foundation of the 'Institute for the Scientific Treatment of

Delinquency' (later Portman Clinic). Pailthorpe met Mednikoff in London

on February 1935 via their mutual friend and Crowley’s former magickal

partner, Victor Neuburg (Neuburg and other luminaries like Havelock

Ellis were co-founders of the Delinquency Institute). At the time

Pailthorpe, who was tall and somewhat severe, was 44, and Mednikoff, who

was shorter, only 28.

Initially Pailthorpe took the role of the doctor and Mednikoff, as her

full-time patient, would provide her with strange, nightmarish images to

interpret. At times he too would analyse them (eg referring to April

21st, 1935): Here all my savagery plays the part of defending mother.

Escape again – meaning that by pretending to defend mother I was

escaping having my real motives discovered. The bent, double-ended penis

symbol is toothed, but in defence of mother [...] the desecrated walls

of the womb, in turn, protect the breast symbol. This I realise is now

no longer a defence of mother but me viciously attacking mother. My

savage teeth are really savage – defending myself. Fear of castration.

That which is to be protected (the stolen breast) is sheltered within

the protectiveness of mother's shattered womb [...] The voluted platform

is pleasant in character – an assumed protection of mother. The vicious

tone of its edge is indicative of its defence of my own penis. The

enclosing nature of the outer symbols again assumes the womb idea –

castration fear sends me back into mother for protection.

After moving to Cornwall together in order to continue their work in

seclusion, the boundary between doctor and patient became much more

blurred. Pailthorpe herself started painting, with positive results that

refuted her experience with Ernest Jones:...it was undoubtedly what I

had been looking for, viz another method of reaching the unconscious and

of bringing it up into consciousness. My own fruitless experience of

seven years of psychoanalysis by the strict Freudian method had left me

a complete wreck physically and psychologically. Others I knew had

suffered in the same way. I had been a most efficient doctor and surgeon

and came to analysis as a necessary part of my equipment when I decided

to specialise in psychological medicine. My career had been everywhere

successful. In the process of analysis my sublimations were all broken

down, but there was the conscious realization of what was causing this,

and the wrecking of my physical health, except the unrelieved tension

and strain of unproductive [.....] over a continuous period of 7 years

(Montanaro, 2010)

Pailthorpe became more interested in the object-relations theory of

Melanie Klein, and the couple’s research primarily concerned with the

recovery of their ‘earliest experiences, even [going back] to those

before we could talk. If that repressed child within us is to be

revived, we shall find it still the infant with the infant’s mode of

expression’.

The couple’s comprehensive, unpublished ‘Notes on Colour Symbolism’

(1935) demonstrate their remarkably articulate theory of colour, in

which each colour symbolised something. They believed that colour was

therapeutic and that the unconscious refuses to work without colour. In

fact, when describing the colours of the mother's womb, Pailthorpe

states that the blue, red and green colours refer to warmth, the uterine

water, the comfort of being cushioned and body odour. She also refers to

the colour blue as a symbol of the mother figure because of its strength

and richness, yellow as representing the outside light, and black as the

symbol of death.

As a published poet himself, Mednikoff already knew David Gascoyne at

the time he met Grace Pailthorpe, and through Gascoyne, was familiar

with continental Surrealist art. It is therefore no surprise that

despite their forays into the unconscious, the couple’s work is not

completely spontaneous or automatic, and instead retains visual echoes

of Surrealists like Andre Masson. Nor is it surprising that, despite

having never shown together before, they were asked to be included in

the 1936 exhibition (Montanaro, 2010). As a professional draftsman and

one-time commercial artist, Mednikoff's work is generally more finished

and more complete in its structure and design, but both artists used the

same convulsive amoeboid shapes, and scatological references to bodily

functions.

Letters written during this period indicate that Pailthorpe and

Mednikoff remained in touch with Gascoyne after the close of the

International Surrealist exhibition, and he probably visited them in

Port Isaac. (eg Gascoyne to Mednikoff, 20th July, 1936): I imagine

you both to be hard at work in your seclusion, and am most interested to

know how it is all going [...] Taking you at your word, I am wondering

whether it would be possible for you and Dr. Pailthorpe to take me as a

paying-guest for a few weeks, if convenient just now. You were kind

enough to offer me your hospitality and, feeling in need of a change of

air and scene, it would be most pleasant to stay with people with whom I

share so much interest in common, and in such a congenial part of the

country.

Dylan Thomas, the

poet, was one of many present at the opening of the 1936 Surrealist

show. Legend has it that, getting into the spirit of the exhibition and

inspired by the antics of Dali and the other Surrealists, he offered

visitors cups of boiled string asking ‘weak or strong?’

An indication of Cornwall’s attraction to London’s bohemia, immediately

prior to attending the exhibition in June 1936 Thomas, too, had spent a

couple of months in Cornwall with Wyn Henderson, an older fiery

red-headed libertine with whom he had a brief affair. In the late 20’s,

Henderson had worked for Nancy Cunard’s ‘Hours Press’ in Paris, where,

as the general manager she published Havelock Ellis’ 'The Re-evaluation

of Obscenity'. (In fact she apparently told Dylan Thomas, proudly, that

Ellis had taught her to urinate standing up (Lycett, 2003)). Returning

to London to live next door to Virginia Woolf’s brother Adrian Stephen

in Gordon Square, she had subsequently helped put Antonia White into

print (Frost in May, 1933). However by 1936 she had been declared

bankrupt and retreated to Polgigga near Lands End, to run a B&B.

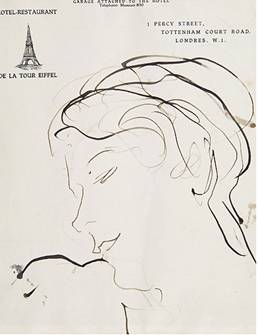

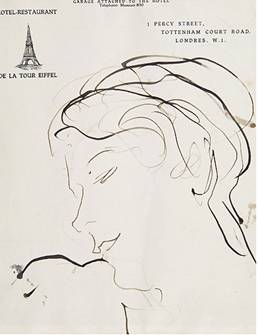

Wyn Henderson by Augustus John on Hotel De La Tour Eiffel paper

By the time Dylan

Thomas returned to Cornwall again a year later, in the summer of 1937,

he had fallen in love with Caitlin Thomas. With the help of board and

lodging from Wyn Henderson, who by then had taken on the Lobster Pot in

Mousehole, he and Caitlin were married in Penzance Registry Office on

11th July. Caitlin and Dylan had their honeymoon in Cornwall and are

known to have met Dod Procter and Indian novelist Mulk Raj Anand, who

cooked them a fiery curry (Lycett, 2003).

There were some other notable Surrealist comings and goings that summer.

In June British Surrealist Roland Penrose organised a month’s holiday

for some of his friends in Cornwall at a house between Truro and

Falmouth, called Lambe Creek. The party included several artists who had

taken part in the 1936 exhibition. ELT Mesens, Eileen Agar, Max Ernst,

Leonora Carrington (his younger, English girlfriend), Paul Eluard, Lee

Miller and Man Ray, all managed to squeeze into a modest, white,

creekside property looking upriver towards Truro. The police had issued

an arrest warrant for Max Ernst on the basis that his recent exhibition

at The Mayor Gallery was pornographic. Despite this, the artists did

little to try to avoid detection, and engaged in plenty of playful

exhibition-ism in the garden on the bank of the Truro River: pulling

shapes, and posing for two of the century’s most renowned photographers,

Lee Miller and Man Ray.

Then in August 1938, occultist Aleister Crowley stayed in the Lobster

Pot in Mousehole. He was visiting friends in Cornwall, notably Pat

Doherty and his son Ataturk. By this time, however, Wyn Henderson, who

had known Peggy Guggenheim earlier in the 30s, was back in London. Early

in 1938 she was asked by Guggenheim to run a new gallery. Henderson

suggested the name - Guggenheim Jeune - and designed the branding. By a

strange twist of fate it would be important to the careers of a number

of British Surrealist artists.

Pailthorpe and Mednikoff were amongst the first to be asked by Henderson

to show there, and would have travelled up from Cornwall for meetings:

Dear Wyn Henderson,

Many thanks for your letter and the enclosed Bulletin.

I expect to be up in London the last week of July (1938) and would like

very much to come to lunch with you and meet Miss Guggenheim.

Is this Peggy or another Guggenheim?

R. Mednikoff and I have been asked to show our pictures at all

surrealist shows since the International in 1936, both at home and

abroad - New York, Chicago, Washington, Boston. We were asked to show in

the Belgium show, but the show eventually did not come off, I forgot

why. I am interested to see that you are showing surrealist works.

I shall look forward to seeing you soon.

John Tunnard was another artist living in Cornwall who visited

Guggenheim Jeune in 1938, and was offered an exhibition there the

following year. Born in 1900, Tunnard enrolled as a student at The Royal

College in 1919, where he became acquainted with sculptor Henry Moore.

Tunnard married Mary ‘Bob’ Robertson in 1926, and in 1929 gave up a

promising career as a commercial artist to become a full-time painter.

He spent most of the next few years in West Cornwall, and when he was

offered a show at the Redfern Gallery in 1933, most of the exhibits were

landscape paintings of the area: naive and expressionistic and similar

in their feel to the 7 and 5 Society era paintings of Ben Nicholson. (Glazebrook,

1977). Tunnard and ‘Bob’ went on to buy a gypsy caravan in which they

lived in Cadgwith on the Lizard peninsula, and he is known to have been

given a copy of Herbert Read’s Surrealism by Bob for Christmas, 1936. He

is reputed to have said ‘it’s all in there, it’s all in there’.

In fact Tunnard drew equally from abstract art, and artists like Juan

Miro, Alexander Calder and Ben Nicholson in arriving at his mature

style. However his use of space, and his habitual tendency to place

biomorphic modernist forms in front of a long featureless horizon, so

they appear to float within a strange futuristic landscape, has always

suggested a strong affinity of with Surrealism, and accordingly he was

included in several Surrealist shows in the late 30s.

It was in 1938 that he presented himself to Peggy Guggenheim: One day

a marvelous man in a highly elaborate tweed coat walked into the

gallery. He looked like Groucho Marx. He was as animated as a jazz band

leader, which he turned out to be. He showed us his gouaches which were

as musical as Kandinsky’s, as delicate as Klees and as gay as Miros. His

name was John Tunnard. He asked me very modestly if I thought I could

give him a show, and then and there I fixed a date’.

PSI by John Tunnard. Shown in the Guggenheim Jeune

exhibition, and bought afterwards by Peggy Guggenheim herself.

Whilst Tunnard may

have only been obliquely influenced by the 1936 International Surrealist

exhibition, the same cannot be said to be true of another artist who

later would be his near neighbour in Cornwall, namely Ithell Colquhoun.

Colquhoun, artist, painter, writer and occultist and Cornwall-ophile was

born in India in 1906. She attended Cheltenham Ladies College before

gaining entry to the Slade School of Art in 1927. Whilst there, she

painted classical and mythological subjects in a modernist, figurative

style and made some tentative forays into the esoteric world of the

Qabalah by getting involved, and contributing to The Quest Magazine. (Ratcliffe,

2003).

After leaving the Slade she went travelling throughout Europe, and

managed to have a formal portrait taken by Man Ray in Paris in 1932.

However Colquhoun only really got turned onto Surrealism after

witnessing the 1936 exhibition in London: When I went to Paris in

1931 I read a booklet called what is Surrealism by Peter Negoe – and

American, I think, of whom I have never subsequently heard. I saw

paintings by Salvador Dali in small mixed exhibitions. Dali had not then

been excommunicated by Breton. Only in 1936 did the movement

(Surrealism) make its full impact on me…..Andre Breton, robust and

thickset, with wavy hair of a length at that time conspicuous, and other

also spoke, but who could follow Dali? It seemed that he did actually

evoke phantasmic presences which generated a tense atmosphere; the white

cloth stretched to form a lowered ceiling vibrated as in a strong wind,

though the weather was still and sultry. Dali was minute, feverish, with

bones brittle as a birds a mop of dark hair and greenish eyes.

Responding to the provocation of Surrealism, and its problematisation of

sexuality, between 1937 and 1939 Colquhoun produced her most

characteristic surrealist works. She subsequently referred to this as

her 'Dali phase'. In June 1939 she had a joint show with Roland Penrose

at the Mayor Gallery, and shortly afterwards visited Paris to see

Breton. She formally joined the Surrealists late in 1939.

When war was declared in September 1939, Pailthorpe and Mednikoff moved

from Cornwall to Hertfordshire, and attempted to organise a Surrealist

exhibition at the British Art Centre. The gallery had been recently

established by Guggenheim and Herbert Read. Previously the British

Surrealists had rather relied on the London Gallery and the London

Bulletin for exposure, and their demise at the outbreak of war had very

much threatened the survival of the British group.

During the lead-up to the event, Mednikoff sent a letter to the

Surrealists inviting them to dinner at the Barcelona Restaurant:

At a meeting between Dr Pailthorpe, Roland Penrose, W Hayter and

myself, it was decided that arrangements be made for a gathering of

Surrealists for the purpose of planning the reforming of the Surrealist

Group in England.

Dr Pailthorpe and I suggested the reforming of the group with freedom

from political bias or activity as part of its constitution. As it was

felt by us all that Surrealism’s vital purpose would benefit

considerably by the reforming of the group, it was agreed that

arrangements be made for a dinner, to be followed by a discussion in

which all views could be made known and a constitution formulated.

The plans for this are now in progress. The dinner will be held on

Thursday, April 11th, at 7.15pm, and the price will be 3/6 per person.

The final arrangements cannot be made until the exact number of people

who will be present is known, therefore, it is essential that I am

quickly notified of your intention to be present. As soon as I receive

this information the address of the rendezvous will be sent to you.

Because there is very little time to spare an immediate reply will be

greatly appreciated.

Yours sincerely

Ithell Colquhoun supported the couple’s arrangements for the meeting. In

a handwritten letter dated 5th April 1940, she wrote: I shall be very

pleased to come to the dinner you and Dr Pailthorpe are arranging to

discuss the future of Surrealism in England. As you know I am in

agreement with your idea of the non-political basis of any group which

may be formed.

ELT Mesens, however, was committed to retaining a much more principled

political stance, prompted by the rise of Fascism, and Breton’s recent

endorsement of Marxism. As the leader he demanded that any one wishing

to remain in the British Surrealist group would have to commit to the

following rules:

1. Adherence to the proletarian revolution

2. Agreement not to join any group or association, professional or

other, including any secret society, other than the surrealist

3. Agreement not to exhibit or publish except under surrealist auspices.

Pailthorpe, Mednikoff and Colquhoun, along with Eileen Agar and Henry

Moore, could not agree to these rules, and left the group. Paithorpe and

Mednikoff ended up moving to the US. Colquhoun, on the other hand,

started visiting Cornwall more regularly, and eventually settled here.

References: Harrison,

C (1981) English Art & Modernism; Remy, M (1999) Surrealism in Britain;

Glazebrook, M (1977) John Tunnard; Read, H (1937) Surrealism;

Lycett, A (2003) Dylan Thomas: A New Life;

Ratcliffe, E (2003) Ithell Colquhoun: Pioneer Surrealist

Artist, Occultist, Writer and Poet.

See Lee Ann Montanaro

(2010)

http://www.artcornwall.org/features/Pailthorpe_&_Mednikoff_Montanaro.htm

see 'exhibitions' for Pailthorpe & Mednikoff's 'A

Tale of Mothers Bones'

Written in 2013 as a chapter in

Magic&Modernity, uploaded in 2019 |