|

Sarah Ball’s

Ordinary People

Martin Holman

Perhaps the best show of a contemporary artist in Cornwall this past

summer was found in a low-ceilinged back room off the downstairs gallery

at Tremenheere Sculpture Gardens. The exhibition is best described as an

impromptu event: it arrived without fanfare and may well have

disappeared before many people had the chance to see it. In its way,

however, it was outstanding for its aesthetic merits. More than that,

though, it achieved the rare distinction in today’s art world of being

active and engaged: up to the moment culturally and socially. Yet the

work never raises its voice above the measured tone of a careful

observation but one that reaches right to the heart of the matter.

That perspicacity was not the isolated

characteristic of one small display of work alone. It marks the tenor of

the artist herself. Sarah Ball is based in Cornwall and is a known

quantity nationally, a position that deserves celebration. She has had

five solo shows since 2012 in St Ives with the Millennium gallery, now

Anima Mundi, and is represented by Stephen Friedman Gallery in London

from where her work has had critical exposure in Ireland and in the

United States. This year she had a solo presentation at the Frieze New

York art fair.

Those exhibitions have almost exclusively featured her paintings, which

are also portraits. That is because her theme is people, and the

depiction of individuals as subjects is traditionally called

‘portraiture’, perhaps the most searching, critical and revelatory of

genres. That definition often applies to the registration of likeness.

But the term reaches deeper and is more diverse. For example, it does

not exclude the representation of a physical being as a material object

like any other, animate or otherwise, as applies to the last 30 years of

Lucian Freud’s career. Portraits can reveal much hidden from general

sight in the sitter and, which is less expected by the viewer, what lies

hidden or unacknowledged in the person who is looking.

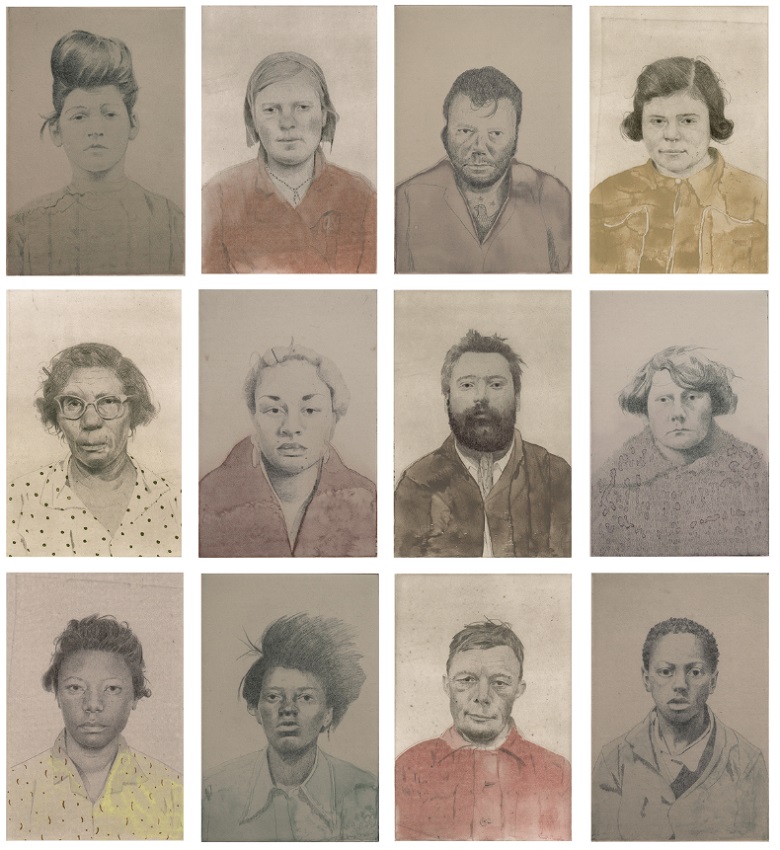

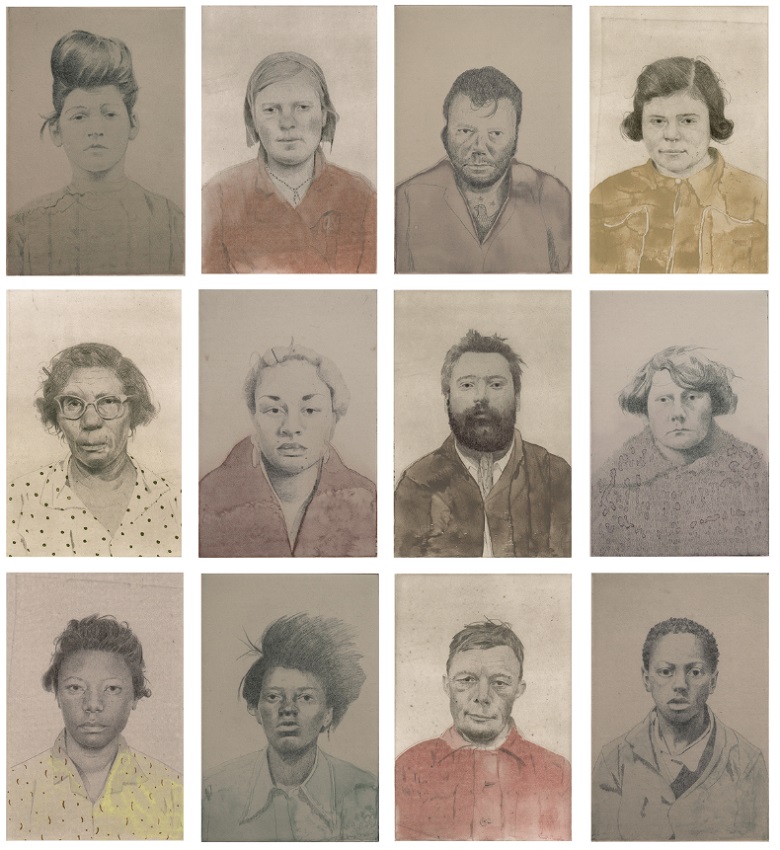

Untitled Portraits, c. 2018/19, etching, 30 × 23 cm,

edition of 25. © Sarah Ball. Courtesy the artist, Stephen Friedman

Gallery, London, and Paupers Press, London

Ball’s work is a case in point. At Tremenheere, her theme varied in

medium only. The images were products of an etching process, the result

of her collaboration in 2019 with Paupers Press, the London printmaker

with a long history of working with leading artists. Most recently,

their partner was James Turrell whose two installations are highlights

of Tremenheere’s permanent offer to visitors. Ball’s show brought

together a group of polymer gravure prints, small in size – the smallest

are 12 cm across and bigger ones are not much larger – and in number:

there were about a dozen of them. In polymer gravure ink is drawn up

into absorbent paper under the pressure of the press from the tiny

grooves below the polymer printing plate’s surface to register the

image. Unlike with painting, which produces a unique outcome, an

artist’s print is reproduced in multiples with a limit assigned to each

edition. This suite forms an edition of 25 copies from each plate.

Ball does not paint or draw from life. Her sitters on this occasion

lived but in decades before the artist was born and their lives are

often a mystery to her. Each portrait was mediated from historical

archives; the most recent of these collections could not have been less

than 40 years old and probably dated back a century or more. All the

images show forward-facing heads and shoulders derived from photographs.

That accounts for the stiff and rather antiquated appearance of the

sitters. Yet there is no question that these faces exert a strong hold

in present time. The small viewing room intensifies the encounter. Each

head stands out from a plain background and sits inside a rectangle

surrounded by a larger border of white paper behind a pane of glass set

within a plain wooden frame. The infrastructure of display (which was

not at the artist’s behest – indeed, it was strangely accidental – but

seemed strangely complementary to the subject matter) makes these small

heads appear smaller still: a small head within a vacant boundary behind

a transparent screen contained by a wooden structure hung upon a white

wall and confined to a small room within a much larger building located

in acres of countryside set apart from the mass of humanity. It should

not have worked but it did. The constrained space resembled an office

and even had a table and chair which, although clear of papers, assigned

a further clerical twist to the installation. Maybe it was the

particular moment that made it gel, coming after months of restrictions

to free movement when isolation from others has been the price paid for

physical health. Art is a form of distancing and to that Ball

highlights, however temporarily, the withdrawal of liberty by an

external authority.

Faces reproduced in art have a particular resonance with viewers: we

scrutinise a head in a way we would never dare do in everyday life

unless for professional reasons, by a medical professional for instance.

Portraiture is an act of both scrutiny and idolatry. For those reasons,

some religious groups continue to discourage the faithful from being

depicted in this way. It fulfils a curiosity to inspect our species

intimately for similarities to ourselves in search of visible traces of

lived experiences. When the faces are unnamed, as in Ball’s pictures,

the desire to fill gaps in knowledge with stories of our own creation is

irresistible.

For this work compels scrutiny. Some viewers, at an early stage in the

experience, will decide these characters are not for them. They look

shifty and under duress, and the concealment of identity is a barrier

that puts people off. Ball is not forthcoming. Gallery information fills

in some gaps towards an explanation. Most significantly we find out that

she retrieves the figures from the administrative dossiers of police or

immigration departments. Government bureaucracies continue to collect

still images to register the transient flow of humanity through their

doors at micro level. They document people caught in a predicament when

individuals do not look their best – in custody for a crime, for

instance, or newly arrived in a new country, in a new continent, a new

reality. Consent was not sought then; not much has changed. Private

images still become official property.

But Ball’s images ask questions and withhold answers. As we look into

and at each one, we are searching. We might, for instance, notice that

while the clothing in the etchings is coloured, the face, by and large,

appears monochrome. The surfaces have a faded, washed out feel; colour

is muted and details sporadic, with usually more in the toneless face

than in the polychromatic clothing. Our own heads quickly fill with

speculation about the sitter’s identity and the situation that brought

the person before the camera. Denied their names, we interpret the

expressions for clues to context. After all, those expressions are often

deadpan at best: one or two smile at the lens. Under instruction, their

eyes are trained on the apparatus. One woman has her head held back in

defiance; a man appears slumped in resignation as if he knows the

procedure already. But mostly these faces look forward blankly or with

apprehension.

Having found this photographic atlas of humanity stored in institutional

files, Ball embarked upon an intriguing task. While undertaking an act

of gentle restitution of the sitter’s individuality – colouring their

clothing or tidying their complexions – she has also retained a sense of

the pernicious bureaucratic aptitude for categorisations which suspends

these physiognomies in the limbo of generalisation. They were not known

to the authorities by name so much as, in the case of migrants, by

country of origin. And for the faces in legal custody, by the

misdemeanour that would bring them before the judge in police court.

Nineteenth-century government in the ‘advanced nations’ surpassed even

the Spanish Empire of the Golden Age with the extent and complexity of

its record keeping. Services were being extended to more and more

citizens, and peoples were on the move, from oppression, starvation and

joblessness in search of a new chance at peace and security across

distant borders, especially in the Americas. Photography became an ideal

tool for keeping track of people who came into the ambit of the state.

By the turn of the last century the technology was relatively quick and

easy to use. Ball’s sources appear to date from that time up to the

1950s. The photographers behind the source material that Ball has used

were mostly untrained, gaining experience by being on the job of turning

their equipment on those who needed documenting, the kind of people who

left precious little other public trace of having existed, except

perhaps a line every decade in a population census.

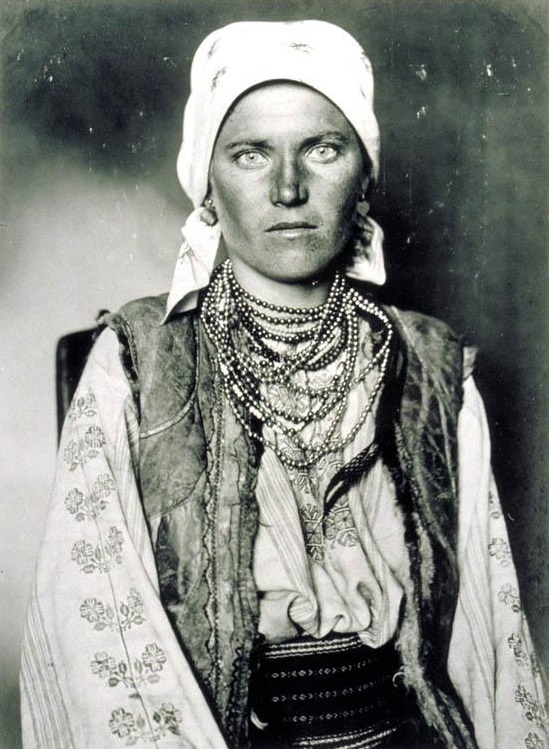

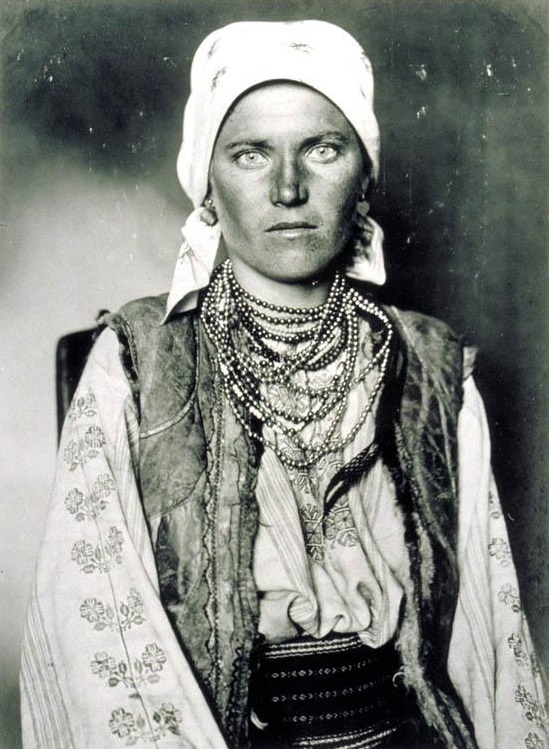

Augustus Sherman, Gypsy woman at Ellis Island,

photograph, c. 1910, © US National Park Service, Statue of Liberty

National Monument

The resources available to Ball will have been dauntingly vast, so she

had to be selective. The archive at New York’s Ellis Island alone

relates to the immigration of over 12 million migrants to the United

States during the 50 years from 1892. Not surprisingly it supplied Ball

with an entire show of paintings, called ‘Immigrants’ at Millennium, St

Ives, in 2015. Oil paint on panels prepared with a smooth surface of

gesso infused these heads, full face or in a three-quarter turn, with a

luminescence that the glass or film negatives could not capture. In

these paintings, the faces acquired colour as if Ball breathed not only

life into them but also restored their humanity as people who once lived

and dressed and walked, who were picked out and sat waiting for a flash

bulb to explode, and then slipped back into the flow of newcomers. In

that show, her paintings were small and barely larger than the original

photograph, but bigger than modern passport prints. Her paintings have

grown in since. Negatives deteriorate and prints fade, but oil paint

lasts. In a sense that is strangely poignant. Ball’s treatment gave

these unknowns new life and new stories.

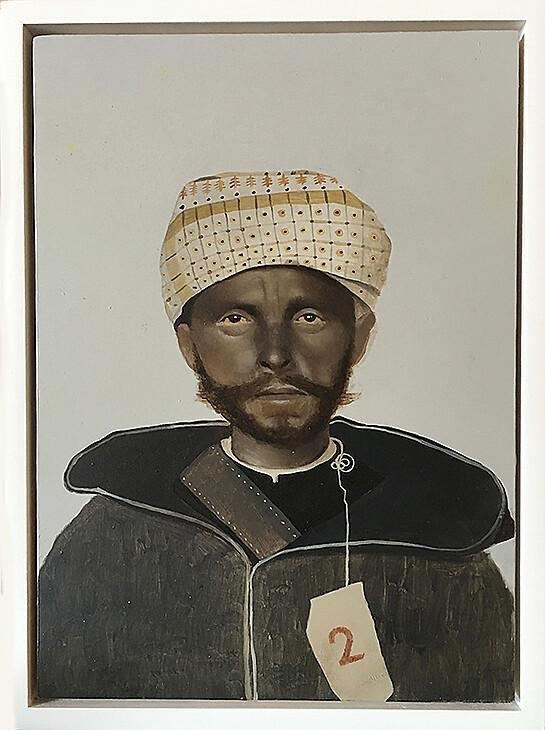

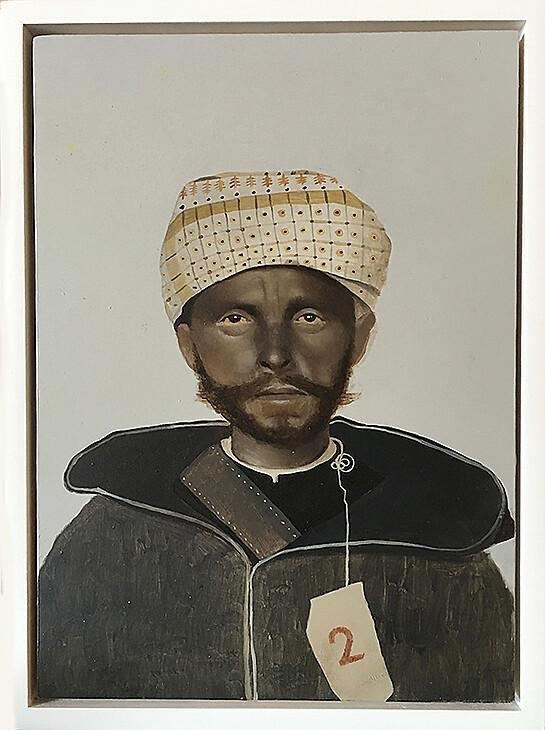

Immigrant Series – Moroccan, 2016, oil on gesso panel,

17.8 x 12.7 cm. © Sarah Ball. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman

Gallery, London

Ball has participated in numerous group shows in the UK and US; next

year will see a one-person exhibition at Stephen Friedman. As well as

‘Immigrants’, five solo shows in St Ives and the US (four solo shows

there since 2014) have often been titled by the type of archive she has

used. ‘Accused’ (2012-14) was followed by a second showing, with

‘Immigrants’, in galleries in Dallas, Texas, where the contemporary

relevance of the work relating to penal policy and migration must have

been inescapable to her audience. In the Trump era, a wall was begun

along the state’s border with Mexico for the singular purpose of halting

the free flow into the US. Another show was titled ‘Kindred’ (2017) for

which, as well as Ellis Island migrants, there were portraits derived

from the recently discovered collection of Romanian army photographer,

Costică Acsinte. He had photographed the Eastern European country from

1925 until his death in 1984, through several upheavals – coups, war and

its aftermath of the shape of a Communist dictatorship which brought

about rapid industrialisation at the cost of the country’s rural

agricultural traditions and architecture. The show featured faces from

across a century that had witnessed immense shifts in culture and

expectation, whether in capitalist America or under the regime changes

of Europe.

Her portraits at Tremenheere reflect on changes in fortune. They make an

enthralling comparison with the fashionable illustrated carte de visite

of the Victorian era that catered for the other extreme of society.

Posed in studios by professionals, these images supplied the trappings

of status - solid furniture, suitable background, baroque curtain and

perhaps a plinth to lean against in the manner of a classical column –

that came courtesy of the photographer and a props cupboard stocked with

generic tokens of genteel accomplishment. These cards were politely left

in their tens of thousands, not only to prospective hosts but, as it

turns out, to posterity. The sitters sought a flattering representation,

one that could stand in for their own attributes of status on those

occasions when such tokens were left in others’ hands.

Every so often an editor

publishes a selection of these aspirational aides-mémoires. Mug shots,

on the other hand, are less well treated although they have as much, if

not, more intrinsic value for future generations. They record a

different interface with society, one that was culturally, politically

and economically regarded as problematic. Occasionally, the two poles of

society have converged: Mick Jagger when busted for amphetamine

possession in 1967; a youthful, tousle-haired Frank Sinatra on a

seduction charge in 1938; or Hugh Grant after being arrested for ‘lewd

conduct’ in Los Angeles in 1995. Anonymity was never a possibility for

these celebrities in custody; they remain nameable.

As flash bulbs were popping in police precinct houses and immigrant

reception centres in front of Ball’s people a century or more ago, the

social scientists of the day were enquiring into the criminal mind. They

were asking if wrongdoing was the product of nature or nurture. The

camera became their research tool. Although the term ‘mug shot’ is a

relatively modern invention, coined around 1950, the format evolved in

Belgium in the 1840s and was soon adopted in the UK and France before

becoming universal. Ball is well aware of this history, which probably

accounts for one series bring titled ‘Bertillon’, shown in the eponymous

show at Anima Mundi in 2017. Alphonse Bertillon was a Paris police

officer with a tidy mind, a family history in statistics and an interest

in anthropometry, the technique of human measurement with the aim of

studying physical variation. In the 1880s Bertillon applied

anthropometry to the question of whether criminals can be identified by

their physical attributes – specifically by head length, head breadth,

length of the middle finger, of the left foot, of the hand’s span. The

camera could provide the evidential link between outward appearance and

inward character. Asylums for patients who were considered then ‘insane’

might have used these documents for their own research into hereditary

factors in mental illness.

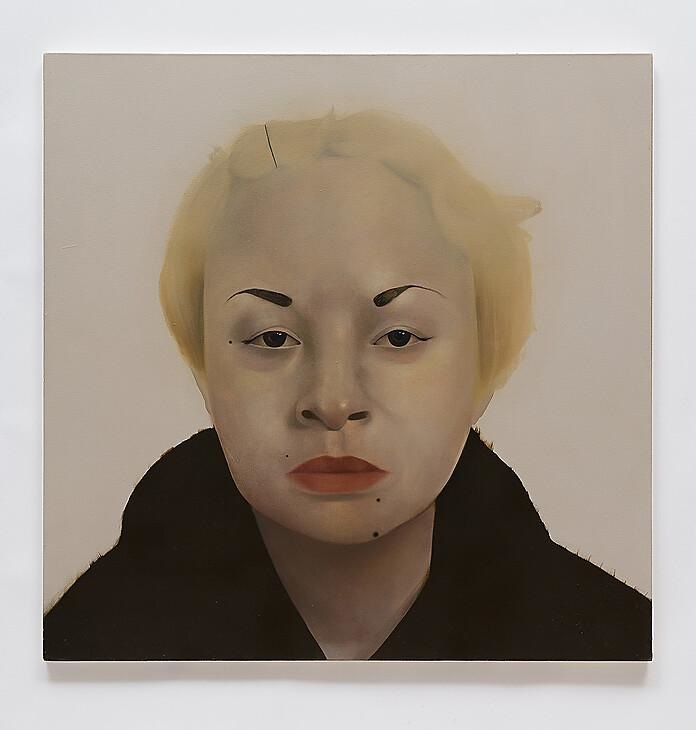

AC 19, 2018, oil on linen, 99 x 99 cm. © Sarah Ball.

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

The essence of Bertillon’s theory was that people who look bad are bad;

either they ‘measure up’ as innocent or they don’t, depending on who is

asking. His assumptions hardly bear examination. But they do reflect the

belief that was widespread until quite recently that the ‘camera doesn’t

lie’. When in league with the caliper or ruler, the evidence was

irrefutable. The lens was popularly presumed to be the objective

register of reality. That individuals seldom look their best in police

mug shots (or passport photographs, for that matter) was inadmissible.

The flaw in the process was long overlooked: it was designed for adult

men with short hair. Women and children were less easily categorised by

this method, although the Minneapolis police department, currently

notorious in the tragic case of George Floyd, used it for decades in

their surveillance of female sex workers. The theory thrived on broad

generalisations about identifiable sections of the community that caused

anxiety in established circles eager to protect its property, its ethnic

superiority and its moral assumptions. An instance of its perceived

value occurred when Bertillon was called as a witness for the

prosecution in the Dreyfus trial.

Anthropometry is no longer the backbone of the criminal justice system;

forensics have supplanted it, another Bertillon project. But Ball is not

pursuing research into historical representation or stereotyping.

Instead the implications of her work are strikingly contemporary.

Without doubt, her paintings and these prints – one led on to the other

– touch the long history of portraiture, its tropes and frailties, and

it stands that history on its head. By choosing the involuntary

portrayal of individuals, the likeness taken under duress, she lives in

the spirit of predecessors such as Théodore Géricault. His sensitive

portraits of the insane painted for the physician, Étienne-Jean Georget,

in 1823 were not the first such pictorial enquiries into appearance, but

they are among the most searing and memorable.

Géricault’s paintings assisted Georget’s studies which had already

produced his book ‘On Madness’, published in 1820. Physiognomy supported

his theory that the state of mind was detected in facial

characteristics. ‘In general,’ he wrote, ‘the idiot’s face is stupid,

without meaning; the face of the manic patient is as agitated as his

spirit, often distorted and cramped; the moron’s facial characteristics

are dejected and without expression’ and so on, further defining the

features expected in the monomaniac, the religious fanatic, the anxious

patient and more. In spite of Georget’s harsh language, his work applied

empirical science to alleviate conditions that society excluded from

serious consideration, in an attempt to trace their social causes.

Géricault’s objective approach delves into the subject’s external

characteristics to detect conspicuous signs of illness in the eyes,

mouth, skin and self-presentation. Maybe it was Georget’s demand for

objectivity that resulted in all the faces being unnamed and known for

all time by their infirmities.

Théodore Géricault, Portrait of a Kleptomaniac, 1822,

oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent

Ball, of course, also divulges little about her subjects: she holds her

cards close to her chest. They are report cards, naturally. Police

records, for instance, would have listed the individual’s offence, so

that one subject is a pickpocket, another a forger, a third a vagrant.

Immigration officials wanted to know from which country the new arrival

had sailed, so they were listed by nationality and quite likely by race,

as Russian, Italian and Jew. They wore the clothes in which they stepped

onto American soil, which might have been their best suit, cut in the

style of the region they had left behind them. Their occupation was also

noted, although no attribute of craft or skill is ever visible in the

image, as it could be helpful to a future employer. Anyway, officers

wanted to know because they were in a position to ask, to intrude.

Ball’s paintings (and these etchings) and Géricault’s, too, provide the

answer to those who wonder why this territory is not left to

photography. Surely, the mechanical registers likeness as well (and more

quickly and cheaply) than the manual process of artists. Edward Weston

and Dorothea Lange, after all, captured the predicament of

Depression-era families more memorably than their painter-

contemporaries. Painting, however, has an approach that is both modern

and timeless; it contains layers of insight that photography cannot

equal. A portrait by Lucian Freud, for example, set next to one by, say,

the leading photographer of the 1960s, Brian Duffy, will highlight the

degree to which painting transposes ordinary subjects into memorable

images.

Ball has borrowed her sitters’ features; if she could seek their

consent, no doubt she would. But time prevented her and, anyway,

forwarding addresses (if known) had probably been bulldozed years ago.

She translated photographed faces from one medium to another, painting,

albeit one with its own cargo of aesthetic and cultural associations.

One of several reasons Ball’s portraits score highly with our

imaginations is that the viewer feels impelled to speculate, to dress

them in new stories. And they provoke serious thoughts about how human

perspectives have changed so little. In stylistic terms, her method

employs appropriation of existing material which she processes in much

the way as Photoshop, by colourising and enhancing. Her technique makes

the viewer think of the controversy of retouching bodily reality towards

an ideal unhampered by wrinkles and bulges. Consequently, Ball’s work

can strike us as a remarkable meditation on present times.

That privilege of self-modification was denied the subjects of the

polymer etchings on show at Tremenheere. These images do not seek

idealism. Rather, they are invested with realism that penetrates the

viewer’s own assumptions. Crime and migration are eternal realities, as

old as mankind. As are the responses of settled populations. Is racial

profiling – the tendency institutionalised in many societies of

suspecting, targeting or discriminating against a person on the basis of

their ethnicity or religion – so different from Bertillon’s application

of anthropometry as a measure (puns are inescapable) for crime

prevention?

The perception of ‘difference’ continues to divide communities along

lines of race, religion and class. Vast numbers of people risk their

lives today to escape poverty and violence as they did after the pogroms

of Russia at the end of the nineteenth century when poet Emma Lazarus

wrote the lines that appear on the lower pedestal of the Statue of

Liberty: ‘Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to

breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore…’ Across the

globe, the complicity of host societies in the pernicious evils of

divided communities is heard in the phrase, ‘You know, the problem is

not with us.’ Meanwhile, governments build walls to resist unauthorised

incomers, either physical obstacles or the poisoned atmosphere of the

officially sanctioned ‘hostile environment’ projected at those presumed

to have no right to be ‘here’. Governments threaten to turn back at sea

the rafts carrying refugees to Europe or Asia, and staff immigration

centres place emphasis on ‘indefinite detention’ and deportation to

‘offshore hubs’ rather than reception and integration.

Ball’s opinions are not on show. She does not invite a classification of

her own, as ‘political artist’. She has selected her material and, once

aesthetically mediated, places her work before the viewer. But neither

can the artist ever be a neutral observer. A painter cannot be a passive

camera lens; like the photographer, she selects and she can edit. But

she need not proclaim. This is the strength of Ball’s work: she raises

the possibility of an ethical position that cannot be evaded. As her

audience stands in front of her canvases or looks into the framed prints

of her show at Tremenheere, the message that comes in their direction is

‘Where do you stand?’ The work resonates with quiet confidence as

searching questions animate the gallery space.

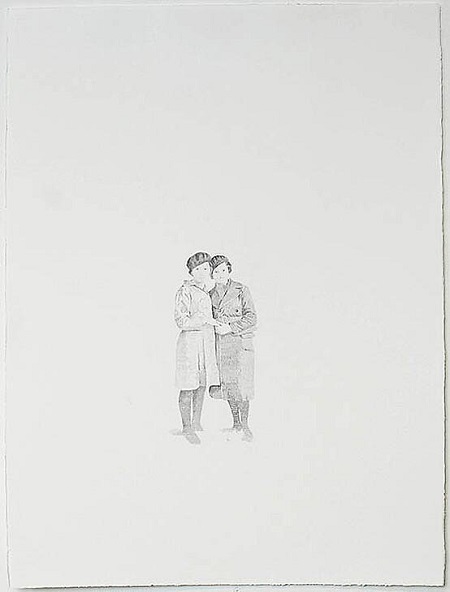

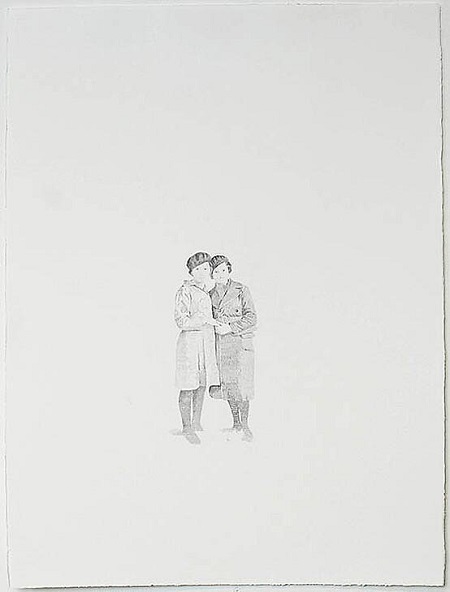

Romanian Series (two women, holding hands), 2017, graphite on paper, 85

x 66 cm. © Sarah Ball. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery,

London

At least, that is one interpretation. These images are open to scrutiny,

the starting point of which has to be empathy for the humanity of the

sitters. The risk exists that Ball’s work will be recruited to support

positions that she herself does not endorse. She came through the art

school system in the 1980s, studying at Newport College of Art and

Design, which is a combination of time and place that brings to mind the

distinctive critical attitude towards the social and political

dimensions of imagery promoted by tutors at Newport. It was imbedded in

photojournalism and, later on, in the structural subtleties associated

with conceptual art. In this progressive and interrogative environment

many students flourished and others, inevitably, floundered. In that

environment, however, could a spade remain only a spade; every action

had an equal and opposite subtext.

In the circumstances, it might be surprising that Ball held on to the

traditional medium of painting. She first practised illustration after

graduation, a direction of career that has a perceptible mark in her

work today. (Like her etchings, her pencil drawings in the past have

been very conscious of the white space of the sheet, positioning small,

carefully delineated figure portraits in an ocean of vacant material.)

But Newport had a reputation for teaching traditional media as

creatively as newer, time-based technologies and of encouraging

independence, both of which emerged in Ball’s painting once she returned

to the idiom early this century, completing a master’s degree in Fine

Art in 2005 at Bath Spa University. Perhaps this combination of

formative experiences shows itself in the compassion and consciousness

that diffuse across her portrayals a vitalising effect on the media of

painting and print themselves. ‘Immigrants, the title of this series,’

Ball wrote about her show in 2015, ‘is a word that has always been

loaded with a meaning and weight beyond the dry dictionary definition.

The word is weapon, a political pawn, a tabloid headline, to the point

that one might forget that we are dealing with human beings.’

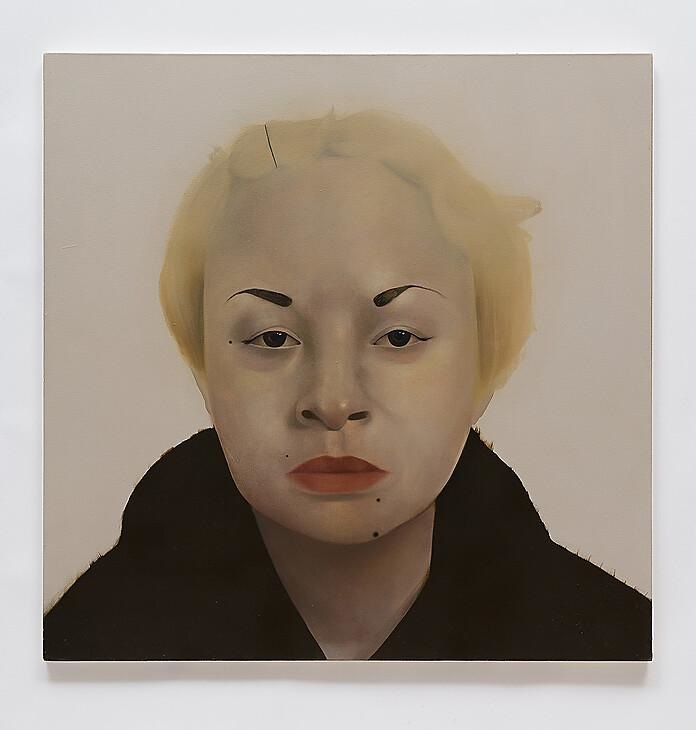

Elliot, 2020, oil on linen, 160 × 160 cm. © Sarah

Ball. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

Her source material has never been exclusively historical. In paintings

from 2020, her focus returns to the present, a moment in which

preoccupation with appearance is acute because the means for

self-portrayal are in everyone’s hands. Now the faces are named and the

individuals are probably living. There is Edie, Lilith, Anthony, Elliot

and more, and they strike us as posed, intentional and knowing, in the

way that mobile phone camera selfies are. Their heads address the viewer

and proclaim their uniqueness by hair styles and dress sense (that we

suspect are also modelled on fashion and ‘tribal’ loyalties); facial

expressions still convey attitude. Indeed, the ‘selfie’ is the latest

challenge by photography to the once unsurpassable hegemony of the

painted portrait, an assault that has been underway for 180 years.

Indeed, with her choice of formats that almost imitate photograph, this

artist may be returning the challenge with brio. For, with Ball, it

seems that not only is what she paints significant, so is how she paints

it – the muted tones, then blocks of colour that stand out like abstract

planes; the blank backgrounds; polished skin tones; and the push and

pull between flat areas and others plumply modelled. The perceptible

trend in these latest works is towards the sugar-coated fashion of

modern Japanese Kawaii or ‘cute’ culture and K-Pop promos. That

development also reflects trends that exist on a higher aesthetic plane

among figure painters such as John Currin, Lisa Yuskavage, Kehinde

Wiley, to reinvent the tired category of genre painting before the

depiction of the human figure is consumed by magazine photoshoots and

pornography. Yet, at the same time, Ball’s treatment of faces and the

upper body has a lineage stretching back to the early Renaissance in

Europe, when formats and media were being tried out and, to an extent,

perfected. An idea of moral and material perfection was achieved in Jan

van Eyck, Giovanni Bellini and Titian, but acquired an additional

ambiguity in the quirky attentiveness to detail of the Cranachs, Dürer

and Hans Baldung.

These latest portrayals (shown at Frieze New York this year) have also

acquired scale over their predecessors. So, as well as the face,

dimensions invite interrogation,

since the larger they get the more the artist’s technique is exposed to

examination and greater the area becomes for abstract subtleties in

texture and form, like in hair and clothing. The process of upsizing

from almost pocket-sized panels to wall-filling canvas started in

2018-19 and was the surprise feature of her last solo show at Anima

Mundi in 2019, called ‘Themself’. Perhaps,

however, the source is not private but, once again, institutional in the

form of workplace identity badge, strung around the neck by a swinging

lanyard. The truth, Ball

might be suggesting, is that anonymity might now be hoped for when our

likenesses are disseminated across numerous channels. Size might imitate

assumed self-esteem, the flaunting of a desired rendition on multiple

social media platforms.

Yet the huge enlargement could underline the view that, in an era where

more and more people struggle to define the identities that suit them,

sensitivities to appearance among adolescents and adults alike are

heightened almost to psychological breaking point by the swift exchange

of likenesses. When identity itself is now more fluid in its

categorisation than ever before in human history, there is no hiding

place from the critical eye of the unseen viewer. Ball’s work is a

reminder that visual rendition is a fact of modern life. Dissolution is

not an option.

© Martin Holman 2021. The author is a writer based in Penzance and a

regular contributor to Art Monthly and the Burlington Magazine.

5.10.21 |