|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

A Quiet Drone Linda Taylor responds to the launch of Patrick Lowry’s exhibition, 'Surveillance', at Hardwick Gallery, Cheltenham

This openness was reflected by Hardwick gallery in its organization of

the launch event for Surveillance. A symposium, with speakers and

readers from the divergent worlds of art and investigative journalism,

provided an opportunity to explore nascent ideas around Lowry’s work

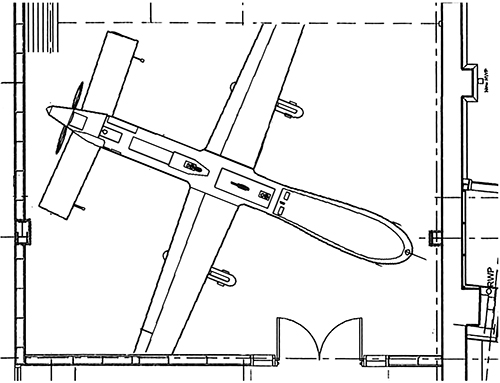

from a range of perspectives. The role and responsibility of investigative journalism in confronting secrecy and power are relatively straightforward and self-explanatory. The role and responsibility of art in the politics of power, on the other hand, are more difficult to determine. Indeed, there remains no consensus as to whether art should have any such a role or responsibility. The problem of how art can meaningfully engage with political, ethical and social matters, without resorting to propaganda and/or dogma, has concerned many artists since, at least, the second half of the twentieth century. It is a problem pertinent to the approach of the second speaker, artist, writer and curator, Theodore Price. Power, secrecy and invisibility are central concerns in Price’s practice. He states his interest in “how we represent things we cannot see”. For artists this is not about an arbitrary creation of visual and narrative speculations – such as those to be found in The Daily Mail and on rolling news channels – when images and hard facts are not available. Art, rather, has the capacity to map a state of not knowing, as much as knowing, and to find expression for our frustrated need for answers against ‘the unreasonable silence of the world’*. In 2013 Price initiated COBRA RES, a collaborative project inviting artists, writers and academics to respond each time the covert and powerful British government crisis committee, Cobra (an acronym for Cabinet Office Briefing Room A, where the committee originally met), convened. Some parallels may be drawn between Theodore Price’s COBRA RES project and Patrick Lowry’s Surveillance. Both projects involve a kind of mimicry; a denatured imitation of the imagery and mechanisms of power. There is a resemblance to parody and satire which critique and expose through exaggeration, subtle corruption and a refusal to collude the absolute seriousness of power. This is, perhaps, more pronounced in some of the works produced through COBRA RES which include contributions from The Guardian cartoonist, Steve Bell and assorted card games, including ‘NATO Happy Families’ and ‘Black Box Trumps’. Patrick Lowry’s replica, meanwhile, performs a quiet kind of parody through a precise visual imitation of what it, emphatically, is not. Returning to the gallery after the symposium, artist, Clare Thornton, read an extract from the prelude to Drone Theory by philosopher, Grégoire Chamayou. The extract comprises a section of an official (censored) transcription of the radio transmissions and cockpit conversations of a U.S. Predator drone crew in Nevada, as they track a convoy in Afghanistan, trying to determine the level of threat. As Thornton read, the assembled audience tensed into an absorbed hush and Surveillance retained its brooding silence. In the stillness, the ambient electrical hum of the building could be discerned – a quiet drone.

|

|

|

There was another silence around Surveillance

– the silence of the artist. Patrick Lowry was, of course, not literally

silent. During the five days he spent constructing the model in the

gallery he was amiable to discussion and questions regarding his

project. I mean, rather, that Lowry has resisted giving up too much

information about his intentions. The accompanying literature is minimal

– a short, straightforward press release and a drily technical

information sheet detailing the specifications of the MQ-1 Predator

(which, in itself, seems to emphasise a gap between abstract knowledge

and experience). Artists are, too often, called upon to explain their

work – to reveal their intentions – as if the artist alone holds the key

to a true and singular meaning. The meaning of any artwork, however, is

not the sole province of the artist and is neither singular nor static.

Instead, meaning multiplies and fluctuates through a complexity of

exchanges between the work, its viewers, its environment and a host of

other variable contextual and cultural factors. Lowry’s relative silence

allows a space around Surveillance in which these exchanges may occur –

allowing it to endure as a set of shifting possibilities rather than

close down as a single statement.

There was another silence around Surveillance

– the silence of the artist. Patrick Lowry was, of course, not literally

silent. During the five days he spent constructing the model in the

gallery he was amiable to discussion and questions regarding his

project. I mean, rather, that Lowry has resisted giving up too much

information about his intentions. The accompanying literature is minimal

– a short, straightforward press release and a drily technical

information sheet detailing the specifications of the MQ-1 Predator

(which, in itself, seems to emphasise a gap between abstract knowledge

and experience). Artists are, too often, called upon to explain their

work – to reveal their intentions – as if the artist alone holds the key

to a true and singular meaning. The meaning of any artwork, however, is

not the sole province of the artist and is neither singular nor static.

Instead, meaning multiplies and fluctuates through a complexity of

exchanges between the work, its viewers, its environment and a host of

other variable contextual and cultural factors. Lowry’s relative silence

allows a space around Surveillance in which these exchanges may occur –

allowing it to endure as a set of shifting possibilities rather than

close down as a single statement.