|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

|

| Reclaiming the rural 2: Rural microcultures

Kristopher

Kohler

I grew up in the countryside, surrounded by working farms, where everyday struggle and practical down-to-earth realities went hand in hand with the sublime and romantic view of the land as something marvelous, even transcendent. It is, and has been for sometime, the critical fashion to draw stark separation between the mundane, often harsh realities of the countryside and the urban perspective of the rural environment as a panoramic spectacle for bourgeois enjoyment: the landscape construed as a stage set for excursions or a vista within which to repose. Indeed the term landscape itself has been criticised for its connotations, for turning the rural into an idealised commodity: a conveniently packaged entity for the enjoyment of the bourgeois gaze.

Then came Art College and the steady realisation that I was not creating work that others considered quite as natural or acceptable an output as I had, up until that point, considered. I was fighting a constant war with my tutor who considered my output too romantic and by no means 'edgy' or 'gritty' enough. I thought much of what he considered edgy to be tired and largely devoid of anything that affected me in any meaningful way. Vacuous replays of old urban concerns, glamorised by association with fashionable galleries, colleges and of course the urban metropolis were not always the work that I considered most important. All I would hear was how the city was the location in which culturally and critically valuable art occurred, but much of this was work that did not affect me in any significant way or speak to me of any vestige of my experience of the world.

The urban centre is full of people, that much

is obvious, and where there are people there follows there is a market

for art. As artists must survive they must exchange their creativity and

their skills or output for money: therefore, goes the argument, make art

for the market in the metropolis. But this art meant little to me, it

was another symptom of the alienation I felt in the face of mass

culture. What I did not understand at that time were the potential

political, economic and theoretical reasons for my visceral reaction.

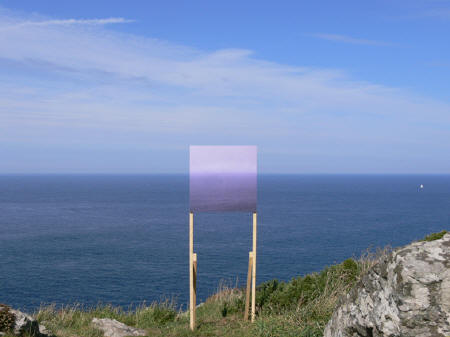

The work, liberated from market requirements, became more ephemeral and transient: a phenomenological experience that worked in conjunction with the landscape context. It became a trajectory, a process that might create a transient shock that, through drawing attention to its incongruity, would cut through the banality of experience. It became an experience of singularisation, situating itself within the grammar of a specific chain of signification, only to disrupt that signification and divert its meanings in new directions. I came to the conclusion that such work was not only valid, but fundamentally necessary. It was work that was necessary not just for rural artists and communities but for society at large. Paradoxically in light of this, it was work that was not in itself confined only to the rural situation but was rather a genre of working derived from the peculiarities of the rural that had a wider position and implications for cultural discourse in all spatio-temporal situations. In the critical discourse of contemporary art attention is directed towards urban, globalised, metropolitan culture which is perceived as the sole site of the innovative or radical. Whilst such a macroculture clearly has much to offer, I have come to believe that such discourse should not and must not overlook the quietly stifled, local microcultures that cling on, mostly in rural contexts, giving a sense of grounding and depth in our increasingly transitory world.

By applying the frameworks of deconstruction and the prevalent cultural models of the postmodern, traditions can become methodologies of singularisation, folklore a contestation, sociality a site of innovation, just as stark, if not more so in the countryside. All that is required is for critical discourse to make the leap and to acknowledge new frameworks that do not necessarily rely on commodity value or huge, impersonal, and often alienated audiences of passive, consuming spectators. The country, the rural, needs a voice within contemporary culture, precisely as what it has to offer is an alterity and a site of contestation of the hegemony of urbancentric models of semiocapitalist, global cultural colonisation. When one does not see one’s own experiences and values represented and reflected back then one starts to question their validity. Human beings cannot exist in isolation - one man on his own does not have a culture. With mass culture and media, as the main manifestations of the dominant cultural discourse, overlooking rural concerns and value systems such systems potentially become undermined and eventually wither. 6) Rosemary Shirley, Country Living AN: The Artists Information Company, 2007. 7)Ibid. pg3

Images on this page (top to bottom) are by Simon Whitehead, Rupert White, Christopher Collier and Jennie Savage.

|

I

began thinking about the problems surrounding rurally situated

contemporary art in response to a paper entitled 'Country Living' by

Rosemary Shirley6). I saw her present her ideas at a conference

in Wales in late 2008 and began to realise that there was a multitude of

artists self-identified as rural operating beneath the surface of

mainstream media and critical discourse. These were often artists, who

whilst not united by any common medium or technique, or necessarily even

by approach, were operating with similar concerns to those which had been developing within my own artistic practice. As Shirley

stated, if one is to collect together the myriad different practices

that are occurring under the umbrella of their common ‘rurality’, this

genre is essentially 'an underestimated, undervalued and often

invisible form of practice'7). I came to believe that this is

what artists self-consciously working within such a field were well

placed to alter, given the wider cultural shifts at play in their

favour.

I

began thinking about the problems surrounding rurally situated

contemporary art in response to a paper entitled 'Country Living' by

Rosemary Shirley6). I saw her present her ideas at a conference

in Wales in late 2008 and began to realise that there was a multitude of

artists self-identified as rural operating beneath the surface of

mainstream media and critical discourse. These were often artists, who

whilst not united by any common medium or technique, or necessarily even

by approach, were operating with similar concerns to those which had been developing within my own artistic practice. As Shirley

stated, if one is to collect together the myriad different practices

that are occurring under the umbrella of their common ‘rurality’, this

genre is essentially 'an underestimated, undervalued and often

invisible form of practice'7). I came to believe that this is

what artists self-consciously working within such a field were well

placed to alter, given the wider cultural shifts at play in their

favour.