|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Relational aesthetics in Cornwall: a reflection on 'Transition: Curators edition' Rupert White

Interactive or participatory art of various kinds emerged as a distinct and important strand within fine art practice in the 90s. Arguably, it anticipated the rise of the internet and reality TV, which, in the mainstream media are comparable phenomena, at least in the way they appear to flatten the hierarchy between consumer and producer.

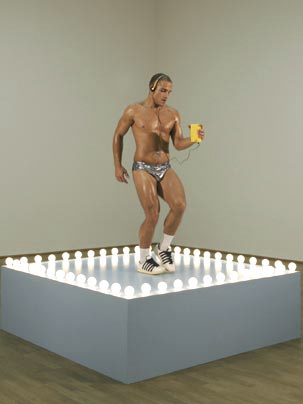

'Relational aesthetics' is a book by the French writer Nicholas Bourriaud, published originally as separate essays but brought together and published as a collection in 1998, and in it he tends to focus on American artists like Felix Gonzalez-Torres as exemplars of this new trend. (He references in particular the go-go dancing platforms (below) and the sweet take aways). In fact, dominated as it was by Saatchi's taste for sensational sculpture and and painting, British art of the 90s contains relatively few examples of relational art, and Chodzko's work, like eg Gillian Wearing's, is far from archetypal. Wikipedia describes the book thus: Bourriaud explores the notion of relational aesthetics through examples of what he calls 'relational art'. According to Bourriaud, relational art encompasses "a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space." A relational artist might, for example, convert a gallery space into a temporary stand for serving coffee, with the addition of background music, suitable lighting, books to read, and comfortable chairs. The artwork here consists of creating a social environment in which people come together to participate in a shared activity. Bourriaud claims "the role of artworks is no longer to form imaginary and utopian realities, but to actually be ways of living and models of action within the existing real, whatever scale chosen by the artist." In relational art, the audience is envisaged as a community. Rather than the artwork being an encounter between a viewer and an object, relational art produces intersubjective encounters. Through these encounters, meaning is elaborated collectively, rather than in the space of individual consumption. Bourriaud believes this collective encounter can be both democratic and microtopian. These intersubjective encounters may literally take place – in the artist’s production of the work, or in the viewer’s reception of it – or exist hypothetically, as a potential outcome of our encounter with a given piece.

This wikipedia description, whilst accurate, understates the intensity of Bourriaud's prose and the boldness of the claims he makes for relational art. For example in the dramatic forward to the book he talks of the demise of the social sphere. Adopting the hyperbolic prose of the Situationist Raoul Vaneighem, he states that '...anything that cannot be marketed will inevitably vanish. Before long, it will not be possible to maintain relationships between people outside these trading areas' and 'the social bond has turned into a standardised artefact'. 'We feel meagre and helpless when faced with the electronic media, theme parks, user-friendly places...like the laboratory rat doomed to an inexorable itinery in its cage, littered with chunks of cheese'. He suggests that contemporary art is continuing a modernist tradition of anti-rational spontaneity and liberation typified by Dada and Surrealism: 'it is evident that today's art is carrying on this fight'. The difference, he suggests is that this fight is less in a private subjective space, more in the public social space. He asks 'is it still possible to generate relationships with the world, in a practical field traditionally ear-marked for their representation?' 'Relational art' has been very much in evidence in the last year in Cornwall. Summer 2007 saw the ProjectBase shows: with Hassan Hajjaj's environment in the Exchange being a very good example, and Surasi Kusolwong's shop, and SUPERFLEX's beer project in particular sharing some of the same features. It was possibly the relational elements that local art audiences appeared to struggle with, yet only a few months later, and 'Transition: curators edition' at the Newlyn in January 2008 featured a number of projects in the same vein. Bruce Davies' 'Lets Play Records' (below), Amanda Lorens' 'Buenos Aries Social Club' (left) and 'Higher Academy of Happiness' (see 'webprojects') all comprised informal environments in which visitors were encouraged to interact both with each other, and with the art and artists. Elements of interactivity were present in less conspicuous ways in all the Transition shows this year from audience participation in Art Surgery's 'Thats Entertainment', to 'Still' and 'Wish you werent here' as part of GreenCube's PSYCHO/GEO-GRAPHY, to Sara Bowlers greeting of visitors to her Offsite:inside. Relational art of the kind described by Bourriaud seems to need the white cube to be a laboratory in which the 'microtopian' social experiment is carried out, which is perhaps why it was such a conspicuous feature of Transition. Whilst art in the private galleries in Cornwall tends to have traditional art-object status, allowing it to be bought and sold, art emerging as part of artist-led activity outside private galleries (eg MORE and Wheal Art Weekend), has had more permeable boundaries. In being site-specific in various ways, it has tended to exploit a dynamic operating between the art-work and its environment. Taken out of that environment, into a setting like the Newlyn Gallery, as it was for Transition, however, and the meaning has to emerge out of relationships set up within work. The art-work, in contrast to the traditional art-object, retains its permeability, or open-endedness, but this time with the audience entering into the artwork and becoming part of it rather than remaining outside it as part of the 'site'.

More importantly, there is also the question of whether relational art can really live up to the claims that are made for it. Is it inclusive and democratic or does it merely replace the observer, audience, or viewer with another set of unequal relations? Does it create a new division between the participant and the non-participant? ie between those that go to contemporary art shows and those that don't? Beech is right to bring Bouriaud's panegyric back to earth, but in general terms, new art and new formats for shows are undoubtedly an important part of the Cornish art scene because of the way they help keep things fresh and moving forward. The challenge is ensuring that the work remains accessible, sensitive to the local context, and critically charged; and that some of the new innovations apparent as part of Transition: Curators edition are developed and built upon in the future.

all the Transition shows are reviewed in the 'exhibition' section of artcornwall.org

Rupert White 12/4/08

|

|

|

The

artist Adam Chodzko, who is showing at Tate St Ives in Summer 2008, made a

work in 1992 called 'The God Look-a-like contest'. It comprised an

orchestrated social experiment in which Chodzko placed an advert in a paper for people

who think they look like God (left); and then photographed them. The result was

an amusing series of portraits in which the artist found himself in a similar

position to the producers of Big Brother: allowing others a brief moment

in the limelight, within a structure which he had created, struggling with the

same ethical issues that derive from the exploitation of

human eccentricity in the name of art or entertainment.

The

artist Adam Chodzko, who is showing at Tate St Ives in Summer 2008, made a

work in 1992 called 'The God Look-a-like contest'. It comprised an

orchestrated social experiment in which Chodzko placed an advert in a paper for people

who think they look like God (left); and then photographed them. The result was

an amusing series of portraits in which the artist found himself in a similar

position to the producers of Big Brother: allowing others a brief moment

in the limelight, within a structure which he had created, struggling with the

same ethical issues that derive from the exploitation of

human eccentricity in the name of art or entertainment.