|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Everyone knew everyone Rupert White A chapter from 'Monstermind: the magical life and art of Tony Doc Shiels'.

In 1958, when Shiels was 20, he moved with his family to a house called ‘Idris’ just outside the main part of St Ives. Tony Shiels: I wanted to meet up with a few lads that I admired, and Peter (Lanyon) was one. He turned out to be my near neighbour in Carbis Bay. His studio was at the bottom of his garden at his house: ‘Little Parc Owles’. It was a place of hard-work: organised chaos, and reeking of ‘paintery’ smells like turps and oils. Shiels soon discovered that there were some very entrenched views amongst the artists in St Ives, but found Lanyon’s open-mindedness refreshing: He became an encouraging friend to me. Peter fell out with Ben (Nicholson) and Barbara (Hepworth) though he had been close with them earlier - he thought they should allow anything in (to the Penwith Society) as long as it was OK - as long as it seemed real. Derek Guthrie founded The New Art Examiner, an influential art magazine, a decade or so later. He remembers Shiels in St Ives: Tony was manic, and his art was ‘activated’. He impressed Peter Lanyon who I think responded to his vivacity and qualities of expression. In a way we were (all) competitors, as young artists, seeking response from the elders. Tony Shiels: I liked Peter Lanyon and the lovely Sheila (Lanyon) very much indeed. Peter introduced me to Norman Levine the Canadian writer. In the early 70’s after Peter had died, when I had a show at The Falmouth Arts Centre, Norman came to the opening with Sheila. 1958, was, in many respects, the heyday of modernist art in St Ives and the time when its reputation was at its greatest. It was the year, for example, that Rothko and Bacon came to stay, and two documentary films were made. Patrick Heron (writing in 1977) put it thus: Outrageous as the present art establishment in London would find it, a case could well be made for considering St Ives the most influential centre of Western painting during the late fifties - at a moment (1957-58) when Paris began its nosedive from unchallenged pre-eminence, but New York's contribution had yet to become apparent outside Manhattan. However, Shiels’ own stay in St Ives was temporarily interrupted. Paul Francis is a painter who Shiels met in Blackpool, who would exhibit paintings at the prestigious John Moore’s exhibition on more than one occasion: The military police traced him to St Ives, as he was supposed to have signed up for National Service. In fact it came to nothing: He got out of National Service by pretending to be insane; claiming to have some sort of sickness or illness.

West Penwith (1959) Oil (Photo Gordon Hepworth) In 1960 Tony and Chris Shiels moved nearer the harbour, to a cottage opposite the St Ives Arts Club, bought from artist Isobel Heath. As well as an aptitude at painting, Shiels had begun to show signs of having a remarkable literary imagination: In 1959 I planned to produce a surreal magazine called Quagga but it didn’t happen. And I wrote my first surreal play - Jackpudding the Worldlooker of Kneedeep Now - and made a recording of it…Jackpudding was of course, a prankster. Now living in the middle of the town, he made more friends. One of them, Vernon Rose, had been at art school in Manchester, but became better known as a folk singer, performing in the clubs that opened later in the 60’s: I came to Cornwall because of my interest in art: I was born in 1930 so I’m about 8 years older than Tony. There were a lot of good people working in St Ives then, not all had been recognised. St Ives was a small compact place. Everyone knew everyone.

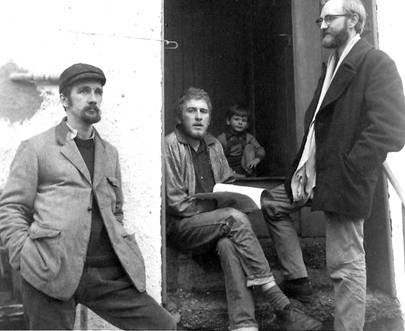

Top: L to R: Vernon Rose, Paul Francis, Gareth Shiels and Derek Barrington on the steps of Tony Shiels cottage (The Cuddy). Bottom: L to R: Vernon Rose, Ewan Shiels (partially hidden), Derek Barrington, Paul Francis, Pat Francis in 4, Back Road West, on the day of Paul’s marriage to Pat. Both photos by Tony Shiels, 1960.

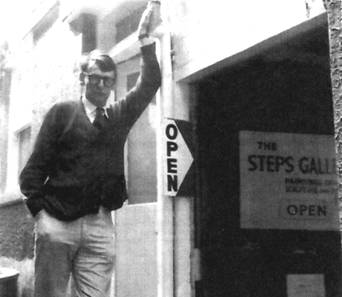

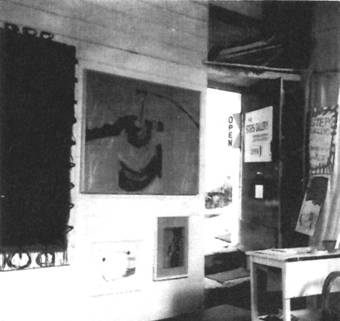

Another contact was painter Michael Dean, who in 1960 founded The Steps Gallery. Accessed from steep granite steps rising up beside 36, Fore Street, the gallery opened on 13/4/60 with an exhibition that included painter, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and potter, Janet Leach. In August a second exhibition featuring Dean himself together with Shiels and sculptor Brian Wall opened (see photo below). Paul Francis, from Blackpool, moved down to St Ives in 1960 to join Shiels, and would become an important long-term collaborator: It would be impossible to exaggerate the passionate excitement and delight that ‘infected’ every moment of my nine months in St. Ives. There seemed to be parties happening every few days. The first and consequently most memorable one was at the Battery on the Island where Nancy Wynn-Jones had invited us (Tony, Chris, Pat and I) to her studio. We met Sydney and Nessie Graham, Tony O’Malley, Karl Weschke, and Alan Lowndes, among others.

'Seahead’ (1960). Typical of the work Shiels was painting at the time, though it is relatively large (48’ by 60’)

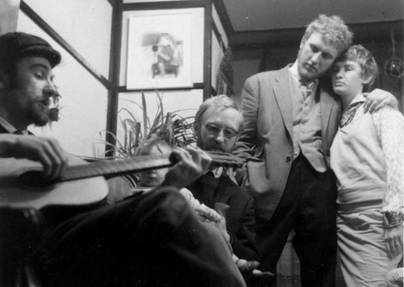

Two views of Michael Dean, the original owner of The Steps Gallery. In the upper image the largest painting is a ‘Seahead’ by Tony Shiels, and the object in the foreground is a sculpture by Brian Wall. A smaller ‘Seahead’ is also visible in the lower photograph. (photos Tony Shiels).

Tony had a studio in Fore St., and I had the top room at St. David's, where we painted our socks off - mainly influenced by our surroundings, and the ‘big boys’- Lanyon, Wynter, Frost, etc. We collaborated on some themes, sketched, and made sculptures. Other friends and acquaintances included Dick Gilbert, Ken Coutts-Smith, Vernon Rose, Brian Wall, Pat Dolan, Benny Serota, and Bill & Boots Redgrave. We met Bryan Wynter, Arthur Caddick and Peter Lanyon, and Tony and I were invited to his studio at Little Parc Owles. Isobel Heath very kindly gave me some financial assistance, by way of part-time gardening and sitting for some portrait drawings. Pat (my girlfriend) got a job in a shoe shop in town, and later I worked at Tempest studios, Lelant, again part-time artcornwall.org. Vernon Rose: Boots Redgrave who used to have a cafe called ‘Daubers’ was a great supporter of the arts. Peter (Lanyon) was a serious worker - very big, business-like studio up in Carbis Bay. He wasn’t at all the bohemian. Nothing wild about him! And Bryan Wynter we used to see in the town. He used to make rice wine, sake.

‘Bird Catcher’: a spontaneous site-specific sculpture made in St Ives with Paul Francis

Tony Shiels also remembers visiting Bryan Wynter at The Carn, an isolated cottage on the road to Zennor that is rumoured was once owned by Aleister Crowley: Bryan Wynter’s pet familiar raven was called ‘Doom’. No doubt The Carn was built on a ‘crow-ley’! I visited Bryan there a couple of times. He knew of the supposed connections with Crowley, but didn’t fret about them. I think Bryan enjoyed the association, fanciful or otherwise. Cornwall revels in its ‘Land of Legend’ reputation. All part of the so-called ‘romantic imagination’. I played games with aspects of this in the mid 1970’s. Sydney Graham (W.S. Graham) was a poet published by Faber, having been championed originally by TS Eliot and more latterly by Harold Pinter. He had lived in West Cornwall on and off since 1944. Vernon Rose: Tony and I were very fond of Sydney and Ness Graham. They were lovely, lovely people. They would stay with Boots Redgrave. Sydney would come to the pub. He was quite a drinker, and you could only visit him if you’d brought a bottle. Shiels and his friends formed a tight, and at times exclusive, clique. Derek Guthrie: I had a show in London, not abstract as was the ascendant criteria of the day. Actually got reviews in the National Press and sold out. When I returned to St Ives and went to the Castle Inn, I joined Tony and others sitting at table. They got up and sat at another table. ‘What’s up?’ I asked. Somebody said ‘We do not sit down with chocolate box painters’. Early in 1961 the Penwith Society of Arts moved from Fore Street to a new gallery in an old pilchard-packing factory in Back Road West, opened by champion of British Modernism: Herbert Read. However, the society continued to be affected by in-fighting, and by criticism that it was dominated by the same older generation of artists. As a result, Barbara Hepworth, by that time the most famous female sculptor in the world, resigned from the committee. Tony Shiels, at the tender age of 22, was elected in her place. It was a measure of his new-found standing in the artists’ community, but it was something he came to regret. It was a great mistake because it often involved me in ugly arguments. In those days many of us became more than a wee bit fed up with the heavy influence of the Hepworth/Leach team. I remember moaning about Barbara to Alan Bowness (later to become the Director of the Tate), who was about to write a catalogue introduction to my early London show. My dealer kicked me under the table, because he’d recently become her son-in-law. I gave a yelp and Bowness laughed. Beatniks had, famously, started to descend on St Ives, and articles and irate letters appeared in the national newspapers as well as the local ones. The town had been described by The Guardian as Britain’s ‘centre of beatnik life’, and local businesses had responded by refusing to serve anyone with a beard. On April 21st a letter signed by Anthony Shiels appeared in the local Times and Echo: …To say it is only strangers who are banned is completely untrue. I am a painter with a wife and family. I own a house here and pay rates, but during the past 3 or 4 weeks I have been turned away from more than half the public houses, with no reason given…

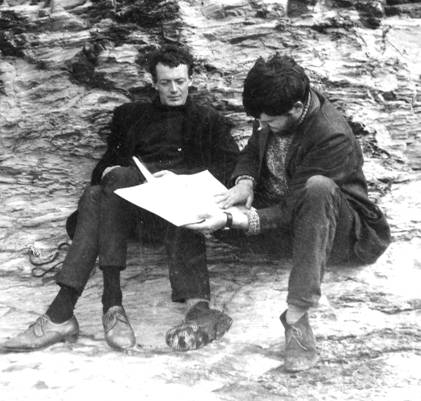

Tony Shiels (L) and Paul Francis (R) on ‘The Island’, St Ives.

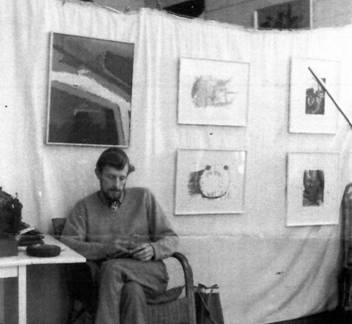

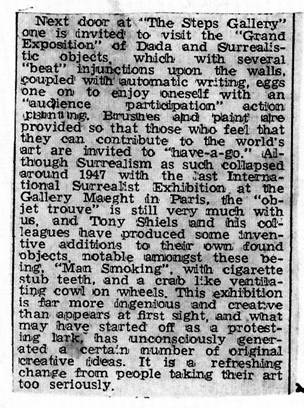

Many of the visiting beatniks were art students themselves who, inspired by the art colony, would later contribute much to the cultural life of the country. One of them was the singer Donovan. Vernon Rose: I remember Donovan busking in St Ives. I went busking in St Ives sitting opposite The Sloop in the late 40’s, singing Burl Ives songs. In those days people didn’t even know what a guitar was – people would refer to it as my banjo. Another was Barry Miles (or Miles) who went on to organise the Albert Hall poetry readings of 1965 with Allen Ginsburg, befriend William Burroughs and The Beatles, and set up underground newspaper ‘International Times’. In 1960 he stayed in St Ives with Paul Francis and Tony Shiels. Paul had been Miles’ mentor at art school in Gloucestershire and had painted a ‘huge mural’ in his house. As Miles recalls: Paul Francis, the only painter we knew who was halfway professional, was often in London or Cornwall…I made a lot of pornographic collages, using images from girlie magazines that Paul had given us…It (St Ives) was like arriving on the Riviera, with the palm trees and an intense blue sea like the Mediterranean. We spent a few days exploring rock pools and collecting interesting bits of sea-sculptured wood…Inthesixties In 1960 Chris and Tony Shiels had a second son, Ewan. Then on Halloween 1961, they welcomed twin daughters, Kate and Meg into the family. After Michael Dean left St Ives, Shiels took over his old studio/gallery space upstairs. Tony Shiels: Below – which was also part of his property – was 36 Fore Street. The Penwith Society used it for a while, and it later became Fore Street Gallery. There was a very good Alfred Wallis exhibition there in 1958. A piano was quickly incorporated into the furniture of the space. Vernon Rose: Steps Gallery inside was a good size for a gallery. We set the piano up by a window overlooking the street up in the corner. We took it there up the steps ourselves – not easy. Photos taken at the time (see picture) show a swathe of white material separating the work area from the exhibiting area. Vernon Rose remembers Shiels working frenetically there: He used to paint like somebody dancing. He’d do page after page after page of more or less the same drawing on big floppy sketchbooks, so when he started painting it’d be very quick, like it was rehearsed. Paul Francis: He would be working in there but members of the public could go in and look around. Ken Coutts-Smith was an abstract painter, writer and art-theorist. We had lots of discussions in the pub with him about abstract expressionism particularly. We put Lanyon in the same category as De Kooning and Kline... An article, written by Michael Canney, appeared in the Cornishman newspaper at the end of April in which Shiels expressed his ambition to show the ‘younger and most progressive artists’ in St Ives. The first exhibition was a solo show for painter Michael Heard, who would appear with Shiels later in a photo-feature in The Tatler magazine. The follow-up exhibition three weeks later was also described in The Cornishman. It included Bob Law’s ‘Nine Wheeler’: a large painting, almost entirely black with a narrow white band around the edges. Tony Shiels: I gave it that title, and Bob liked it. Bob didn’t show with The Penwith. Bob was a good friend of mine and a good painter. He objected, as I did, to what you might regard as the St Ives School – St Ives middle-of-the-road modernism. I thought of it like that, though I was more part of it than he was. In 1960 critic Lawrence Alloway responded to the austerity of Bob Law’s paintings and organised some important exhibition opportunities for him. As a result he became the only British minimalist painter of the 70’s to gain a true international reputation. Shiels: Lawrence hated the St Ives abstracted landscape thing which I fell for but only for reasons of humour. It’s possible he came into my gallery. I did encounter the feller…He shouted at Terry Frost as I recall...I think ‘f off’ may have been involved! Lawrence Alloway had decided to promote pop art... Bob shared a house with my friend Sam Dresner in Nancledra. Sam was in St Ives for about a year. But then Bob objected to Sam’s girlfriend - who was also at Heatherley’s - turning up. Bob’s work was a form of field painting and he claimed in his mock innocence that he got it from Peter Lanyon. Although Shiels had arrived in St Ives a disciple of mid-century modernist abstraction, like Bob Law he was growing impatient with it, and in July he put on a surrealist show at Steps entitled: ‘Exposition of Wonders and Delights’. A lot of local artists went surreal for the occasion. My reasons for mounting such a show had to do with my rapidly changing attitudes towards the rather ‘clubby’ atmosphere of the colony and its polite styles of painting and sculpture. I wanted to be genuinely subversive. The opening took place on the 4th of July, with rousing speeches by Arthur Caddick, Phil Newth, Vernon Rose and others.

Two shots of Steps Gallery after Tony Shiels had taken over running the space. Mike Heard (above) had a solo show, which was followed by a group show (below) that included Bob Law’s Nine Wheeler, partially visible to the left of the photograph.

Steven Cousins: (The show) involved one of the walls being covered with sea-weed stapled in the shape of a sea head; he also produced a collage of raw meat which eventually went rotten entitled ‘The Pleasures of the Flesh’.

Bob Law (left) and Tony Shiels (right) scheming on the beach in St Ives c1959. In the 70’s Bob Law became known as the UK’s most uncompromising minimalist painter. Both Law and Shiels, in their own ways, went on to achieve international reputations, and both, in their attempts to challenge ‘middle-of-the-road modernism’, were accused of being frauds or charlatans.

Exposition of Wonders and Delight included ‘beat’ injunctions on the walls. Article by Michael Canney in The Cornishman.

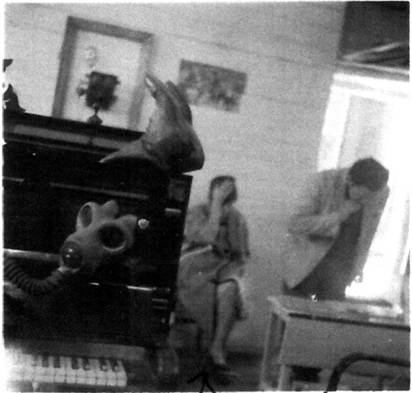

Tony Shiels: The ventilator cowl on wheels (described in the Cornishman) was mainly constructed by painter Pat Dolan. We also had ‘The two-backed beast’ which was a piano and a harmonium strapped together, containing awful reminders of WW1: objects like military belts and gasmasks. I eventually filled them with turpentine and set them on fire. We had to douse it eventually as the whole place would have burnt down! Vernon Rose: I was in another exhibition when Tony was there called ‘When did you last see your Dada?’ and hung by the door was a little axe and a hammer with a notice saying you could destroy all the works if you wanted to…

With its door open to the street, a partial glimpse of the ‘Exposition of Wonders and Delight’, 1961 at Steps Gallery: one of several attempts by Tony Shiels, as artist-curator, to challenge the dominance of ‘middle-of-the-road modernism’in St Ives. In the foreground is Shiels’ prepared piano, which was set alight in the course of the show. Also pictured are Chris Shiels and Patrick Dolan.

Tony Shiels: Those Surrealist shows were very important to cut through the Nicholson-Hepworth thing. A lot of the other artists enjoyed that stuff. Terry Frost loved that sort of thing. He had one of the Porthmeor studios, and became a good friend of mine. With his profile in the community continuing to grow, on 26th July The Tatler published photos of Shiels alongside nine other rather more established St Ives artists. The photographer was Ida Kar, who at the time was married to Victor Musgrave, owner of Gallery One in Soho. In 1961 Shiels also had two exhibitions in London. One was at The Mingus Gallery, in Marshall Street: a space run by poet and hipster Neil Oram, who had previously been the owner of beat hangout Sam Widges jazz café in Soho. The large oil on canvas: Seahead (1960) is known to have been one of the works shown there. I first met Conroy Maddox the surrealist in St Ives circa 1960. When I had my first London exhibition at Gallery Mingus (named after Charles Mingus), Maddox wrote a nice review for Art News and Review (which became Arts Review).

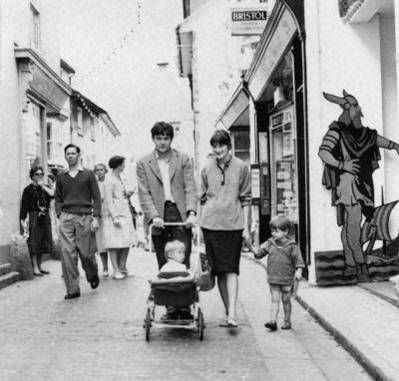

Tony Shiels pushing Ewan Shiels with Chris and Gareth near The Steps Gallery in Fore Street, St Ives. Photo Ida Kar (1961).

The other London exhibition that year was at the blue chip Rawinsky’s Gallery off Carnaby Street: a two man show with his friend from St Ives, Dick Gilbert. This turned into rather a raucous event: Myself and few fellow half-Irish people were arrested at the opening of the show at Rawinsky for having a fracas. Henry Rawinsky came down to St Ives. He ripped everyone off, but then he’s an art dealer! He had a load of my work, and never returned it. One piece was used on a record cover: session musicians doing Beatles’ music. Kevin McGlue was by then living in London, and studying sculpture at St Martin’s with Anthony Caro. Tony and one of the others were having a play fight in the street. Ultimately four of us ended up overnight in the police-cells.

‘Figure’ (1960). Gouache.

Since becoming more established in St Ives, Shiels’ paintings had become like Peter Lanyon’s: gestural, abstract-expressionist works loosely inspired by the landscape, or incorporating the round form of the ‘Seahead’.

‘Nude, Yellow’ (1961) oil on board. The only painting illustrated inside the 1962 Rawinsky exhibition catalogue. (Photo Steven Cousins)

However by the time future Tate director Alan Bowness came to write the essay for the catalogue for his second show at Rawinksy’s, held 1962 (opened on May 30th), he had started incorporating angular female bodies into the designs. Although damned with faint praise it was quite a coup having any kind of endorsement:

I first noticed Anthony Shiels’ paintings in a small St Ives gallery some two summers ago. They owed much to other painters working in Cornwall – Peter Lanyon in particular – but this isn’t surprising (or discreditable) in a young artist’s work. In any case, the pictures, mostly small gouaches with landscape subjects had a distinct quality of their own – they were done by someone with a natural ability to make interesting pictorial compositions and a real feeling for paint and colour. Shiels has continued to develop. His recent oils have been mostly of the figure, and image both generalisd and particular, as the landscapes were. The nudes are more ambitious and personal, and perhaps less completely successful but they have the same painterly freedom and ease that distinguished the earlier work. Anthony Shiels is certainly a young painter to watch.

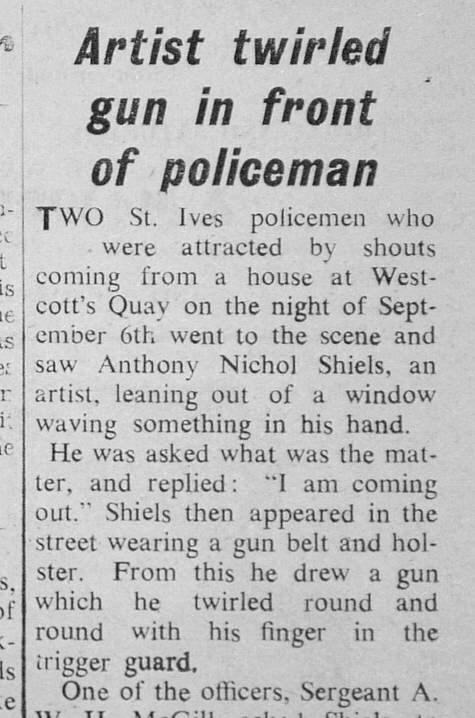

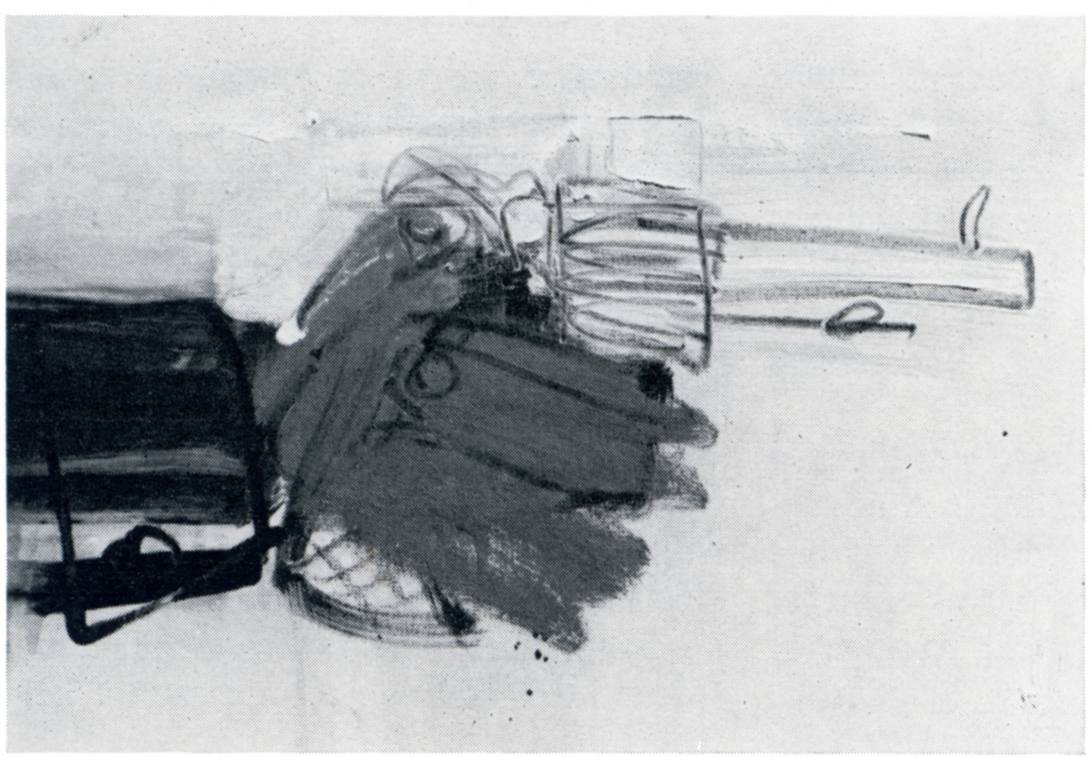

In the autumn of 1962 Tony Shiels was in a three-man exhibition in Colchester, and ex-St Ives sculptor Sven Berlin published his libelous roman à clef: ‘The Dark Monarch’. Within a couple of weeks it was withdrawn again under threat of legal action. Vernon Rose: Sven Berlin was a bit before Tony’s time but I used to know him quite well. He was the archetypal bohemian. Very striking, handsome man, always sunburnt. Always wore a big loud checked shirt and a big belt with a brass buckle and a sailor’s cap. At a time when a number of artists were introducing references to the mass-media into their work, during 1962 Shiels started to incorporate imagery from cowboy movies into his paintings; part of his generation’s engagement with Americana. I have rarely met a painter who didn’t enjoy a good cowboy film. Most would certainly prefer to watch Kirk Douglas as Doc Holiday rather than Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh! SSStatement But Shiels was never one to do things half-heartedly. Vernon Rose: When he lived at The Cuddy, he used to get interested in different things at different times and for a while he was mad keen on the Wild West, and did lots of painting relating to it, and in pursuit of this he got a beautifully hand-crafted gun-belt and a big cowboy hat that he’d wear. Then towards the end of the year, on 16th November, 1962 an article appeared in the St Ives Times and Echo.

St Ives Times and Echo, 16th November 1962

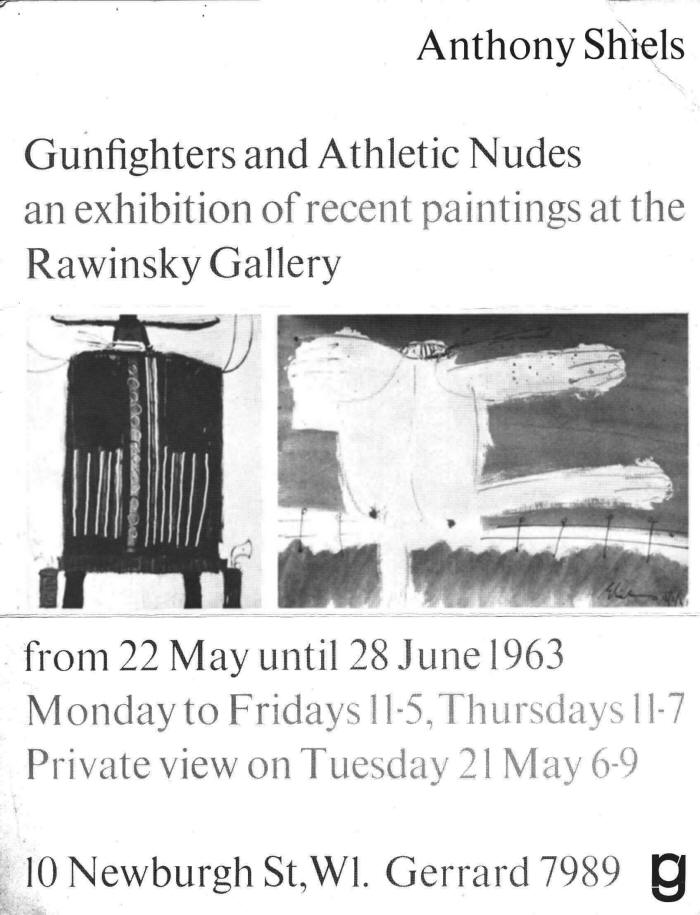

It explained that Shiels had ‘twirled’ a gas-powered gun on the street outside The Cuddy in front of three policemen, one of whom had also confiscated an unlicensed Colt ‘45 with ammunition that Shiels had in the cottage. In fact the article only told half the story: I also had a Smith & Wesson ‘33, and an old-fashioned Winchester ‘73 in the house. The article explained that the Colt ’45 had come from the painter Terry Frost: Terry was annoyed because the cops had a real go at him for giving me workable guns. Terry was ex-army. He’d been a commando and a prisoner of war. Vernon Rose: That night he was out of his head on drink. Tony was a good painter. But he didn’t get on because he doesn’t like dealers or art galleries. He’d behave very badly at the openings. And I mean very badly. Paul Francis: Tony was sectioned, and went into St Lawrence’s Asylum. He’d got carried away with the Western theme. He became a gun-fighter and did it publicly when he’d had a drink or two and got into trouble that way. He ended up moving to Dursley near Stroud in Gloucestershire because of that incident. His mother came down to stay with me and my wife to help him find somewhere to rent. They were very worried about him. He was also partly financially reliant on his parents, who would have had good reason to take the view that the hard-drinking bohemian environment of St Ives was not very healthy for him. Derek Guthrie: Tony played the piano with gusto, as he drank with gusto. His father either modified or withdrew the allowance. Certainly he removed him from St Ives. Apart from a predilection for alcohol, Tony is regarded by his friends as psychologically robust, though he was undoubtedly a risk-taker and he relished confrontation. Vernon Rose: He would rant and rage and get into trouble. In St Ives the police knew him...he’d do all these daft things - pranks and that - and he’d actually want them to arrest him. They’d get called out and they’d say it’s only Mr Shiels again – alright Tony? Paul Francis attended another private view in London: In 1963 Tony held his second one-man show at Rawinsky’s in Soho (‘Gunfighters and Athletic Nudes’), which was attended, among others by painter Peter Blake, who afterwards took a group of us to the Establishment Club, where we saw Lenny Bruce, then on to Michael Chow's famous restaurant in South Kensington - a night to remember! The Rawinsky show received coverage in a number of publications including the widely read Apollo Magazine, which mentioned the fact that Shiels had been ‘letting his gun off in all directions’, but the experience wasn’t altogether satisfactory. Kevin McGlue: Henry Rawinsky made him pay towards the cost, and I think he ended up losing money. In 1963, after five eventful years, Shiels finally left St Ives with Chris and his four young children.

Catalogue for Tony Shiels’ second one-man show at the Rawinsky Gallery showing both a ‘gunfighter’ and ‘an athletic nude’. (photo Steven Cousins)

Detail of ‘Billy The Kid as Pat Garrett’ 1962 Oil on canvas (from Apollo Magazine)

|

|

|