|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

The Artist as Hero(ine): Modernism v Rebecca Warren at the new Tate Rupert White

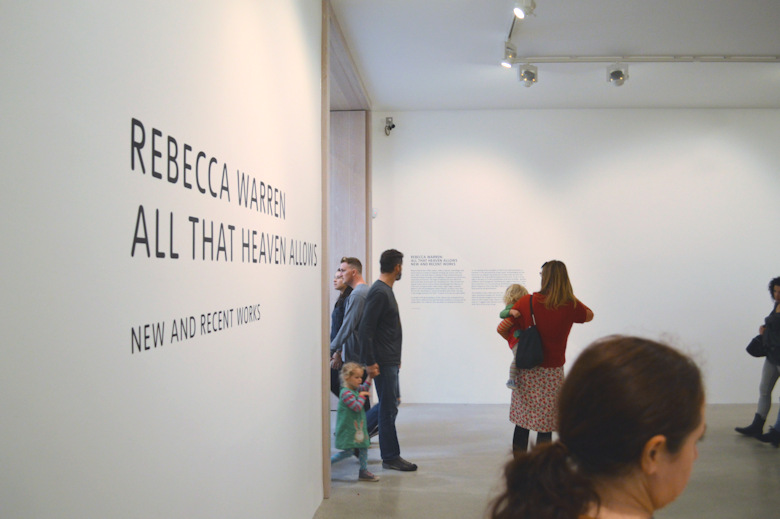

Jonathan Jones of 'The Guardian' rarely comes down to St Ives. However, this weekend saw the opening of architect Jamie Fobert's dramatic new gallery space at the Tate and, as a consequence, Jones was one of many art critics and commentators drawn to West Cornwall to see it for themselves. He didn't much like Rebecca Warren's show 'All That Heaven Allows', though, and in his article ('Creepy comic carnival on the edge of Cornwall' - published 11/10/17) suggests that it compares unfavorably to the Modernist exhibition in the adjacent Evans & Shalev galleries: 'Unfortunately, the abstract artists who created the St Ives school are much more at home here than the first contemporary artist to show in its grand box of a new exhibition space. Rebecca Warren is left seeming like a metropolitan interloper who’s not sure why she is here or what her art is for'. Warren's work is also condemned as being parodic: 'The trouble with parodies of 20th-century modernism is that they ultimately suggest a lack of belief in any purpose to art. Leaving Warren’s show and contemp-lating the Hepworths and Ben Nicholsons you have to admire the idealism and vision of the artists who, in the last century, headed for Cornwall to find some kind of truth'. Though Jones' comments largely ring true, they deserve to be unpicked a little more. Should we expect art to have a 'purpose', and what is meant by the phrase 'some kind of truth'? It is undoubtedly the case that the two parts of the building contain very different exhibitions. The subterr-anean hall of the new gallery, with its twinkling lights and pristine surfaces, can, in fact, be glimpsed from the other end of the pre-existing building, as there is a long line of sight running down its length. And, in a reversal of the previous flow of visitors through it, you get there by passing through four rooms that between them tell a compelling and fascinating narrative about the emergence of modern art in Britain, and the far South-West's undisputed role in it.

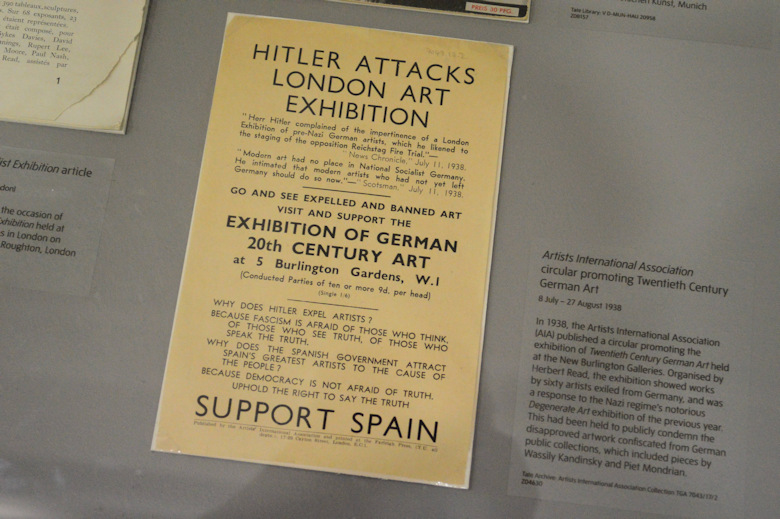

The story spans two World Wars, includes Hitler and the Nazis, the landscapes of Cornwall and the bombing of London, and it takes in politics, idealism, and a seemingly profound belief in progress through art. This epic account, which includes a cast of 100's, is very seductive, and the art works themselves are packed together with many of the paintings hung in rows in order to fit them all in. In fact it is the most in-depth and rewarding Modernist show at Tate St Ives that I can recall, and there are very welcome appearances by lesser known Cornish artists like Ithell Colquhoun and John Tunnard, as well as an opportunity to see classics by the likes of Peter Lanyon, which go down well with partisan locals, who all know he was a Cornish boy. Then, as you approach the new gallery, hollowed out of the hillside as it is, the space opens up and there is a new high-ceilinged atrium with bare walls (picture below), that leads on to Rebecca Warren's show. And here, suddenly, the tone changes: it becomes lighter, more playful and off-the-cuff. Warren's trademark figures rise up from the newly laid floor, like strangely bloated stalagmites. Bulbous geological growths, decorated with pom-poms and Mothercare-pink paint, they totter precariously over the many visitors who mill about, admiring the shiney new architecture and taking selfies.

The change in tone is partly to do with the impressive new gallery space and the relatively sparse installation of sculptures within it, and partly with a step-change in the narrative. In terms of the chronology of artworks there's a jump forwards; you bypass the 70's and 80's and arrive fair-square in the mid 90's at a time when artists in London, like Warren, weren't the slightest bit interested in Cornwall, or in fact anything rural, or landscape-derived. As a result the triumphalist story that links Cornwall to certain important Modernist values fizzles out, rather miserably, and Warren's work is seen to emerge from a seemingly more cynical metro-politan post-modern vacuum, where the notions of progress through art, and the artist-hero(ine) have come to seem laughable and ridiculous. A cogent and compelling 'master narrative' addressing post-modern British art has not yet been written, though perhaps it will in the future. Until then it will be tempting to view most contemporary art as lacking purpose, to use Jones' phrase. In contrast, the Modernist narrative that Jones tacitly plays along with, has now become so entrenched, so rigidly fixed in the imagination, that it's easy to forget that such stories tend to be constructed after the event by historians that create myths around the figure of the artist, who is depicted as a hero battling against the odds, fighting for the spiritual and moral high ground. Modernism has, for years, been presented as a heroic march of progress in the face of adversity, and British modernists including those associated with St Ives have inevitably been given the same 'hyping-up' treatment, starting with the seminal books published in the 80's by Peter Davies (see artcornwall.org 'interviews') and Tom Cross.

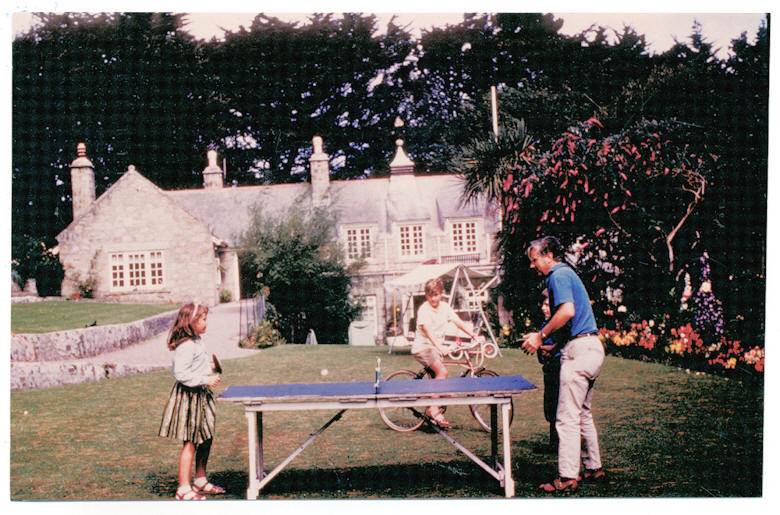

However, at the risk of sounding mean-spirited, it should be said that these same historians have tended to play down important details, like the fact that all the best known St Ives artists, with the exception of Terry Frost, came from well-off families, and so were not really reliant on painting sales for their incomes. Having 'private means' was therefore a crucial factor in allowing them the opportunity to experiment with new art forms. Peter Lanyon (pictured above at his house Little Parc Owles) despite his left-wing leanings, had family wealth that was derived from tin and copper mines of West Cornwall, and much-loved though he is by local artists and other Cornish residents, his ancestors could have been guilty of exploiting a very poorly paid workforce in years gone by. Put in this kind of context the heroism of the St Ives artists, like other Modernists can undoubtedly be exaggerated. These older artists, whose work we still admire now, found they could live in an aesthetically beautiful and unspoilt part of the country, passing their time doing something creative and enjoyable alongside other like-minded people. What's not to like? Where was the idealism and heroic struggle in that, exactly? Perhaps, in reality, this was their 'purpose', and this is the prosaic 'some kind of truth' to which Jones is referring. If so, the art of our own more cynical times may not be so different to theirs after all.

see 'exhibitions' for installation shots of both shows 18/10/17 |

|

|