|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

The Three Hares – A Sacred Medieval Westcountry Symbol Tom Greeves

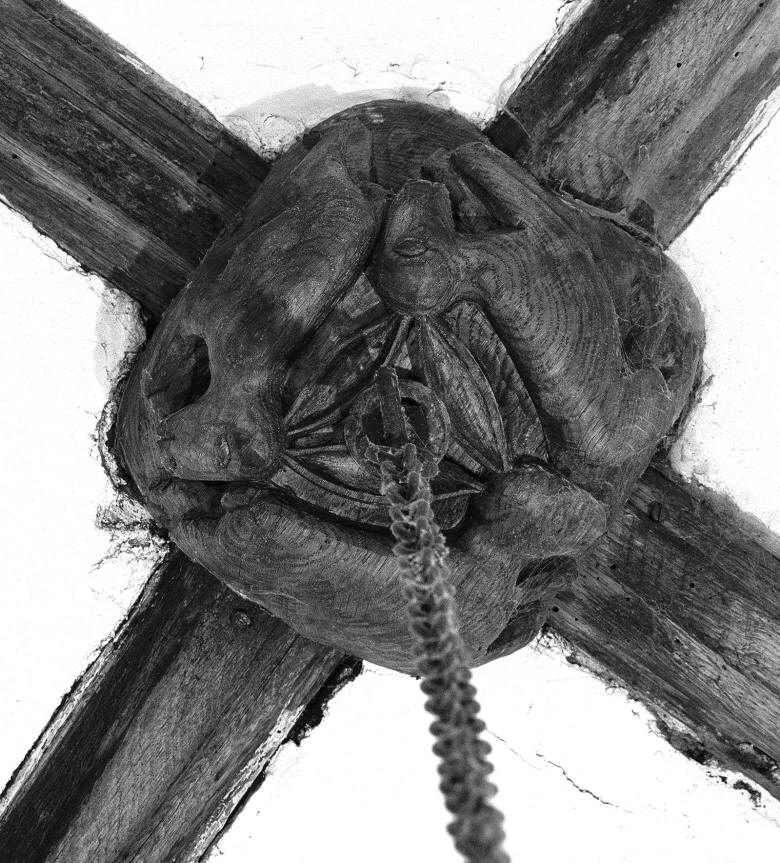

Occasional records of folklore associated with hares and witchcraft have survived in Devon and Cornwall. The pioneer folklorist, Anna Eliza Bray, wrote of shape-changing hares and witches in west Devon in the early nineteenth century.¹ Robert Hunt’s magisterial Popular Romances of the West of England (1865) includes a tale of a white hare in Cornwall.² The novelist Eden Phillpotts, who immersed himself in Dartmoor culture, noted that hares were considered sacred to hunters on Holne Moor and referred to ‘cryptic mysteries hidden in hares and toads’.³ Most recently, Paul Broadhurst, in The Secret Land – The Origins of Arthurian Legend and the Grail Quest (2009) has explored in detail the theme of the hare within the Cornish landscape and imagery, arguing that there is a ‘Great Hare’ imposed on the land between Caradon Hill and Liskeard, linking it specifically to the moon.⁴ Twenty years have passed since myself, with photographer Chris Chapman and art historian Sue Andrew, initiated the ‘Three Hares Project’. Our intention was to record as many examples as we could find, in Britain and beyond, of the motif of the Three Hares – three creatures, in a wondrously clever, pleasing and paradoxical design, each with two ears, yet with a total of only three ears forming a triangle between them. Our quest has taken us throughout England and Wales, into France, Germany and Switzerland and, remarkably, to China where the earliest known examples occur in sacred Buddhist caves at Mogao near Dunhuang, dating as far back as about AD 600. There are several examples of the symbol’s appearance in Europe in about AD 1200. Our focus has been on recording Three Hares dating before the Reformation of the early 16th century, and we have found the motif occurring in Buddhist, Christian, Islamic and Jewish culture, in sacred or clearly special secular contexts, with the creatures usually described as hares (rather than rabbits).⁵ In Devon no fewer than sixteen churches have surviving examples of the motif as a wooden roof boss dating from the late medieval period (mostly 15th century), and at Broadclyst there are plaster copies of medieval bosses. Seventeen Buddhist caves at Mogao in China have painted examples dating between AD 600-900, usually as the centrepiece of the internal roof design. In eastern France there is another cluster of about fifteen stone carvings, mostly in churches. Elsewhere, occurrences are more isolated or are on moveable artefacts. Beyond Devon, but still within south-west England, we know of single medieval examples in Cornwall (Cotehele chapel), Dorset (Corfe Mullen church) and Somerset (Old Cleeve church).

Distribution map of medieval Three Hares in south-west England (© Skerryvore Productions Ltd)

The earliest known printed description of the motif in Britain dates to 1717 in a book written by Browne Willis.⁶ His fellow antiquary William Wotton had in 1716 sent Willis a description of a stone roof boss of ‘three Rabbets’ in St David’s Cathedral in Pembrokeshire. Most significantly, despite their wide reading and enquiries, they were unable to explain the design, whose meaning by then had been lost, and Wotton referred to it as ‘a Curiosity worth regarding’. In Devon, the earliest written descriptions of the motif date from the 1840s when the antiquary Davidson noted several examples in Dartmoor churches. At Ilsington and Widecombe-in-the-Moor he described the design as being of ‘three hares’, but in Broadclyst and Sampford Courtenay he referred to them as rabbits. By the mid-20th century Dartmoor was perceived as the domain of the motif which, through misinterpretation, became labelled as the ‘Tinners’ Rabbits’.⁷ This was cemented by Ruth St Leger-Gordon in her book The Witchcraft and Folklore of Dartmoor (1965). She retracted her support for this label in a newspaper article two years later but it was too late – her book had become the definitive word.⁸ As it happens, there is no connection whatsoever between the tinners of Dartmoor (or Cornwall) and the motif, but the myth is persistent and still current, with the beasts also being referred to as the ‘Tinners’ Hares’⁹ and even, seen by me in a leaflet in Widecombe church, as ‘St Piran’s Rabbits’! This creation of a modern myth is itself of interest, but it does not help our quest to understand what the motif might mean. In the post-medieval period, from at least about AD 1600, the hares appeared in an alchemical illustration by Basil Valentine said to represent the ‘Hunt of Venus’, but their meaning in this context is obscure, to say the least.¹⁰ Intriguingly, at least one of our westcountry examples of the Three Hares, in the church at Corfe Mullen in Dorset, was carefully designed to fit the geometrical concept of the ‘Daisy Wheel’.¹¹ Sometimes considered to be a protective, apotropaic symbol, the ‘Daisy Wheel’ was in fact a core element of medieval architectural design – using a compass to draw a succession of overlapping and intersecting circles and lobes enabling precise calculation of dimensions of buildings etc.¹²

Alchemical illustration of the ‘Hunt of Venus’ by Basil Valentine c.1600

Within medieval Christianity hares can have a negative reputation, due to their abundant procreativity, sometimes bizarre behaviour and supposed hermaphroditism, and also being associated with lechery and lasciviousness, but mostly the symbols seem to have a benign and highly positive character, especially within Buddhism and Islam. In modern times in Devon the three beasts were considered to represent ‘Hope, Health and Happiness’.¹³ It is perhaps curious that no mention of the motif has yet been found among westcountry folklore, though the same is true of the so-called Green Man image which is much more widespread and which is not infrequently juxtaposed with a Three Hares boss. So what might the Three Hares have represented in a medieval context within south-west England? My personal opinion is that the clever carving could have been used didactically with multiple interpretations (some more simplistic than others) – as a warning against lust and sin (with potential for redemption), as a reminder of the phases of the moon, or the stages of life, as a Trinitarian or feminine fertility symbol, as a mathematical paradox, and as a celebration of the skill of craftspeople. That it was borrowed by the key religions of the Old World, travelling thousands of miles across the Eurasian continent, spanning at least 900 years of specific use, always with sacred or special status, is a justifiable cause of wonderment. The clusters in Devon, eastern France and in China clearly deserve deeper scrutiny. As a symbol for our own time it has particular resonance – in a world riven by religious and cultural intolerance, its life-affirming appeal remains an inspiration for artists and craftspeople across the world, who continue to absorb its genius through the expression of new versions in a wide range of media. Our quest continues, and new discoveries continue to be made.¹⁴

Three Hares roof boss in Throwleigh Church, Devon, late medieval (© chrischapmanphotography.com)

Three Hares roof boss in the chapel at Cotehele c.1500 (© chrischapmanphotography.com)

Three Hares stone boss in Corfe Mullen church, Dorset (© chrischapmanphotography.com)

Notes & References

first published in The Enquiring Eye #4 (Autumn 2020) 25.6.21 |

|

|

_small.jpg)

_small1.jpg)