|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Altermodernism: helpful or harmful? Rupert White

In the inchoate soup of contemporary art

discourse, concepts that offer clarity are appealing. Hence, for some,

the initial promise of 'Altermodernism'. What better way to provide a path out of uncertainty than to coin a new term for the essence of art now: a term that is catchy, pronounceable, and

non-threatening? But what might Altermodernism signify? Does

anybody really know? And is the concept helpful or harmful? To use Bourriaud's words:

Altermodernism can be defined as that moment when it became

possible to produce something that made sense starting from an assumed

heterochrony...it is neither a petrified kind of time advancing in loops

(postmodernism) nor a linear vision of history (modernism), but a

positive experience of disorientation through an art-form exploring all

dimensions of the present...the artist turns cultural nomad...Thus the

exhibition brings together three sorts of nomadism: in space, in time

and among the 'signs'. By the same token, multiculturalism as a critical methodology 'a system of allotting meanings and assigning individuals their position in the hierarchy of social demands, reducing their whole being to their identity and stripping all their significance back to their origins' is, controversially, seen by Bourriaud to have become out-dated and dispensible. (Interestingly this was a view rightfully criticised on one of the painted boards in the show by Bob and Roberta Smith, where it is likened to the glib claim that we now live in a classless society). Bourriaud again: 'There are no longer cultural roots to sustain forms, no exact cultural base to serve as a benchmark for variations, no nucleus, no boundaries for artistic language. Today's artist in order to arrive at precise points takes as their starting point global culture and no longer the reverse. The line is more important than the points along its length'. Critics have been lining up to take lumps out of the exhibition and the catalogue that accompanies the show. The most lethargic and least insightful write-up, by the way, was in The Times who really couldn't be bothered with either. At the other extreme was Stewart Home who, in his blog, criticised Bourriaud's depiction of modernism and post-modernism as over-simplistic :'modernism and modernity are inseparable from a process of globalisation that was already in motion in the sixteenth century; and rather than marking a break with modernism, ‘post’-modernism is actually a continuation of modernity'. Mixing up intellectual analysis with personal invective, he also, amusingly, described Bourriaud as a 'Parisian fashion-poodle'.

Her summary of altermodern was n't bad though: The Altermodern, it would seem, is

essentially about global culture. The starting point of Post-Modernism,

curators suggest, is the question “where am I from?” But now, thanks to

such innovations as the internet, we need no longer define ourselves

within traditional boundaries. The artist is a wanderer, drifting about

in space and time, drawing from a vast, fluid fund of collective ideas. Firstly altermodernism doesn't sound different enough from post-modernism to be a useful concept. More important, though, are some of the subtexts to the exhibition as a whole. For example are n't Bourriaud and the Tate simply trying to promote and thus valorise globalised art production? Certainly Bourriaud is keen to suggest that artists who operate globally or who make altermodern art are somehow resistive of globalisation: which is ridiculous. I would suggest that, clearly, the opposite is true - that local and regional art scenes strongly rooted in place (including that in Cornwall for example) are more genuinely resistant to recuperation and the homogenising forces of global capital. The problem is that it doesn't suit the Tate, and other big players, to admit this.

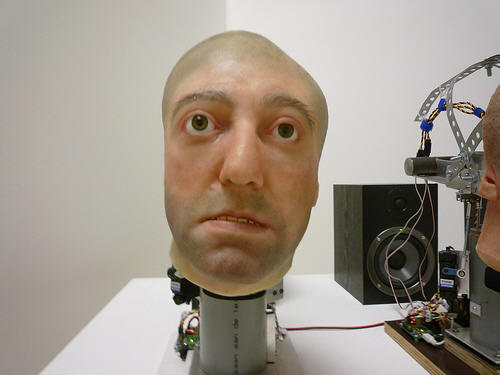

all photos sourced from flickr |

|

|

In his essay for the Tate triennial of the same name, Nicholas Bourriaud

describes, in the space of seven or eight pages, how our relationship with

time (history) and place (geography), has changed irrevocably in the

last 100 years. The account goes something like this:

In his essay for the Tate triennial of the same name, Nicholas Bourriaud

describes, in the space of seven or eight pages, how our relationship with

time (history) and place (geography), has changed irrevocably in the

last 100 years. The account goes something like this: The process has continued to the point now where culture, viz the

art-world, has become global in ways that it has never been before.

Whereas European modernist art before the war was elitist and the domain

of a select few, contemporary art of all shades and colours now shares a similar language and is recognised across the world. In

a way that is analogous to other types of cultural production, it has,

for better or worse, become global in its reach and, contentiously,

subject to 'a common interpretation'.

The process has continued to the point now where culture, viz the

art-world, has become global in ways that it has never been before.

Whereas European modernist art before the war was elitist and the domain

of a select few, contemporary art of all shades and colours now shares a similar language and is recognised across the world. In

a way that is analogous to other types of cultural production, it has,

for better or worse, become global in its reach and, contentiously,

subject to 'a common interpretation'. Bourriaud suggests that 'altermodernism' is a response to the

globalisation of art. Artists, or some of them at least, now engage with

global culture in new ways. As partially demonstrated by the artists

chosen for the Tate exhibition, they do this by weaving between and

across cultural forms, linking seemingly disparate histories and

locations, not themselves showing a particular allegiance or investment

in one cultural or national tradition. The result, he suggests, is art

that is individual and inventive, which tends to resist the drive to cultural

equivalence or homogenisation.

Bourriaud suggests that 'altermodernism' is a response to the

globalisation of art. Artists, or some of them at least, now engage with

global culture in new ways. As partially demonstrated by the artists

chosen for the Tate exhibition, they do this by weaving between and

across cultural forms, linking seemingly disparate histories and

locations, not themselves showing a particular allegiance or investment

in one cultural or national tradition. The result, he suggests, is art

that is individual and inventive, which tends to resist the drive to cultural

equivalence or homogenisation. The

Times write-up by Rachel

Campbell-Johnson was less acerbic but more perplexed. Campbell-Johnson

picked up on the word 'viatorisation' which jumps off the pages of

the catalogue like a

unidentified flying object. It is another obfuscating neologism: a word

that does n't exist in any dictionary or even on the web (try a google

search: you won't find it!).

The

Times write-up by Rachel

Campbell-Johnson was less acerbic but more perplexed. Campbell-Johnson

picked up on the word 'viatorisation' which jumps off the pages of

the catalogue like a

unidentified flying object. It is another obfuscating neologism: a word

that does n't exist in any dictionary or even on the web (try a google

search: you won't find it!).  Its

plain to see that the danger comes from corporate and institutional

forms of cultural production and distribution which always seek to

extend their reach and their influence. This includes eg Hollywood, Disney, Star Bucks and Burger

King and, to a similar though lesser degree, the Tate and blockbuster

exhibitions like Altermodernism. Importantly this is not a level playing

field either: America and its corporate allies continue to dominate it.

Genuinely believing that there is therefore 'a common interpretation'

is therefore both extravagant and harmful.

Its

plain to see that the danger comes from corporate and institutional

forms of cultural production and distribution which always seek to

extend their reach and their influence. This includes eg Hollywood, Disney, Star Bucks and Burger

King and, to a similar though lesser degree, the Tate and blockbuster

exhibitions like Altermodernism. Importantly this is not a level playing

field either: America and its corporate allies continue to dominate it.

Genuinely believing that there is therefore 'a common interpretation'

is therefore both extravagant and harmful.