|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Now, then, and again: between anniversary and HERitageDr. Alexandra M. Kokoli

Should a movement which aspired to be revolutionary and which to a large degree remains wilfully countercultural commemorate the anniversary of a change in law, rather than continue to seek the radical transformation (if not overthrow) of the entire political system and its legislative powers? In marking the 40th anniversary of the introduction of the Sex Discrimination Act (1975), curators Day+Gluckman are aptly ambivalent, as are the artworks brought together in this exhibition. No (un-ironic) celebrations of gender equality can be found here; instead, gender equality is intersectionally exploded and re-presented as a question, as pressing as ever.

The results often bear the scars of their past marginalisation and repression: thoroughly dismissive of chronologies, wilfully fractured, implacably disorienting. As Julia Kristeva’s much cited essay ‘Women’s Time’ indicates, feminist temporalities are never a simple affair and tend to throw pre-existing conceptualisations of time into crisis 3). Liberties, across and between feminist moments and movements, should be approached as an opportunity if not a provocation. These staged encounters between works and (inevitably) their contexts potentially make up a DIY historiographic kit in themselves, suggesting ‘alternative historical affinities’ beyond chronologies 4).Mieke Bal’s notion of ‘preposterous history’ liberates comparative discussion from the limitations of origins and sequence. Bal argues that when a contemporary work of art quotes past practices or alludes to past artworks, this does not hold significance only for the new artwork but also the one quoted from, because the interpretation of the quoted work will have to take heed of its own quotations hereafter: ‘this reversal, which puts what came chronologically first (“pre”) as an aftereffect behind (“post”) its later recycling, is what I would like to call preposterous history’ 5). According to Clare Johnson, this reversal of ‘pre-’ and ‘post-’ (or rather, their complete untethering from sequential order) ‘can lead to the dissolution of matrilineal logic’ and, like Foucauldian genealogy, it draws attention to ‘the dissipation of events outside of any search for origins’6). Related to the concept of ‘preposterous history’ is another that emerged in the recent writing and art practice of Mieke Bal: anachronism as ‘a tool to understand things not “as they really were” but as how things from the past make sense to us today’7). Feminist anachronistic and preposterous histories fabricate flexible and open-ended spaces in which the past and the present can make sense, together, to and for each other, while also disposing of the mother-daughter plot and its insidious baggage.

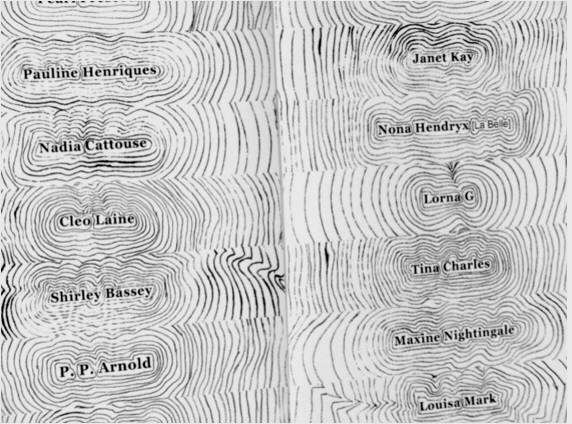

Feminism’s scepticism towards history infects the future and past alike. Archives, curated collections, official and unofficial acts and practices of commemoration, memory and cultural visibility remain prevalent as both issues and structures in art informed by feminism. ‘The Devotional Wallpaper’ (2008-pictured abovex2), part of The Devotional Collection (1999-) by Sonia Boyce, consists of a collaboratively assembled archive of music in vinyl records and other media and ephemera by black British women artists working in the music industry. This ‘devotional’ work could be interpreted as ‘a roll call of 200 female luminaries, memorialised as a large-scale printed wallpaper’9), even though the ambiguity of its format is hard to shake off: simultaneously unimportant and all-enveloping, ubiquitous and thus invisible, wallpaper can never become monument because it is - literally - part of the furniture. Moreover, inclusion is not tantamount to a straight-forward tribute:Many of the named performers would probably hate being collected under that rubric. The act of collecting is not on their behalf, it’s not to represent them. It’s really about an unplanned way that a diverse range of public listeners have built a collective memory.10) Boyce’s history/memory mashup offers different possibilities to feminism’s perennial problems with time and its records. Future uses are not only beyond the control of the past11), but there is no past independent of the acts of memory and recall to come. The Devotional Wallpaper makes an ambivalent backdrop for the entire Liberties show, which offers a glimpse of a diverse and vibrant HERitage, unapologetically, generatively and forever preposterous.

1) Spero cited in Joanna S. Walker, Nancy Spero, Encounters (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), p. 90.2) Ibid 3) Julia Kristeva, ‘Women’s Time’ (1979), The Kristeva Reader, ed. Toril Moi (Oxford: Blackwell, 1986), pp. 187-213. 4) Clare Johnson, Femininity, Time and Feminist Art (London: Palgrave Macmillan), p. 10. 5) Mieke Bal, Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), p. 7, emphasis in the original. 6) Johnson, Femininity, Time and Feminist Art, p. 69. 7) Mieke Bal, ‘Frankfurt’ [blog post, 2011]. http://www.miekebal.org/news-events/2011/09/29/frankfurt Accessed: 15 June 2015.8) Alice May Williams, We Can Do It! (v.3) (2014),Accessed: 15 June 2015. 9) Sonia Boyce, ‘Scat: Sound and Collaboration’, http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/sonia-boyce/. Accessed: 12 June 2015.10) Ibid 11) Ibid This essay was commissioned for the exhibition LIBERTIES: An exhibition of contemporary art reflecting on 40 Years since the Sex Discrimination Act, at Collyer Bristow Gallery, London (July - October 2015) and reprinted for The Exchange, Penzance (October 2016 - January 2017). The exhibition is part of A Woman’s Place project curated by Day+Gluckman. www.dayandgluckman.co.uk/theprojectsee 'exhibitions' for installation shots of the show in Penzance |

|

|

For

feminism in its many diverse manifestations, anniversaries present a

deeper

For

feminism in its many diverse manifestations, anniversaries present a

deeper