|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Abigail Reynolds on The Mother's Bones, assemblage, localism and the St Keverne Band

Interview by Cat Bagg and Rosie Thomson-Glover (Field Notes)

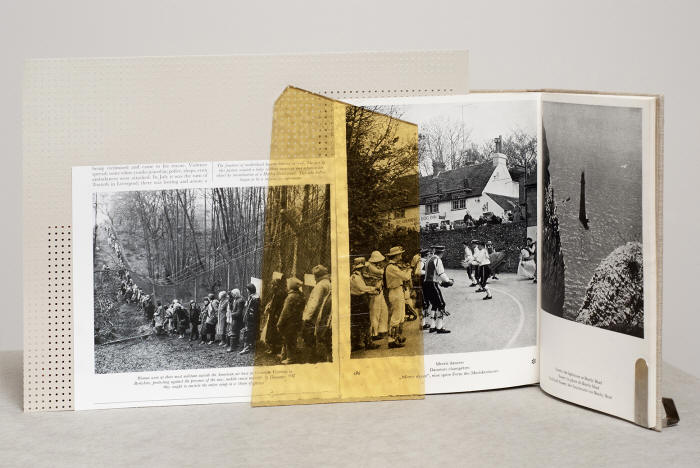

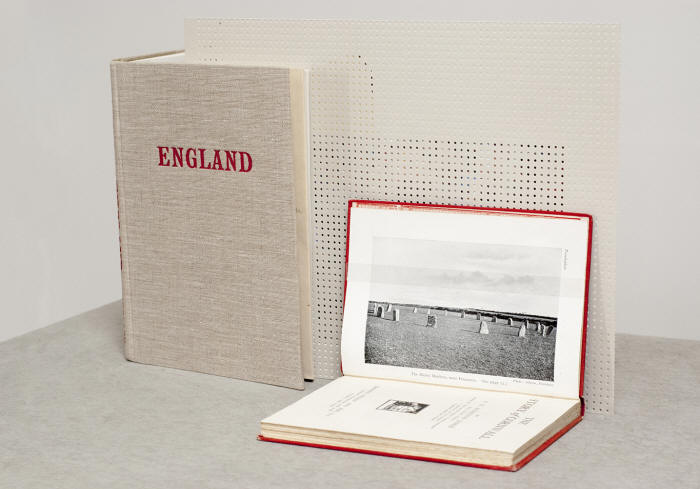

Weíre really pleased to be talking to you about your new work 'The Motherís Bones'... Weíve been linked for a while, because when you curated 'Rituals Are Tellers of Us' you included two of my works: The Maidens and The Witch's Hat. Then the first Inland Art Festival included Double Brass. The Motherís Bones is bound up with those earlier events because they all share a sense of ritual; meaningful gestures made at particular times for reasons that are communal, rather than an individuated personal reason. Thatís always the same; whether in The Maidens (a piece that included an image of the Merry Maidens stone circle near St Buryan (picturex2 below)) or whether it is Double Brass (a live performance for two bands that circle each other in a field at high noon on the summer solstice)...

The Motherís Bones was born from Double Brass (picture below. Also see 'webprojects'). I had this idea for the band to perform in Dean Quarry which Iíd walked through years before. I knew it as a strange and off-limits place Ė the sort of place that attracts me in a trespassing sort of way. St Keverne band began as a quarry band, and as I wanted to work with the land in a direct way it seemed the band could be a direct route by which to do it. A social way. By 2014 I had this quite trusting relationship with Gareth, the band leader. Straight after Double Brass 2014 Gareth and I walked the quarry with some band members, and we found a sound mirror. Thereís a place in the oldest part of the quarry where, if you play at it, it speaks back to you because of the shape left after the stone has been quarried. Itís so beautiful and strange. Having found this sound mirror I felt like we had to do this piece, which I called ĎThe Motherís Bonesí. I asked Gareth to compose a work for his band to play to the stone, using the interval of the sound mirror so everything is aligned.

Can you tell us about the title, which comes from a Greek myth, and how that links to the quarry? When I was a child I had a huge appetite for Greek Myths and also Norse Myths. The darkness of those stories is still attractive to me, and doesnít pall with repetition. I used to take out the same two books from the library opposite my house week after week. Having started work on The Motherís Bones I was reading the story of Deucalion and Pyrrah (which I had forgotten) to my son as a bedtime story when I realised it was at the heart of the work I wanted to create. In this myth, humans are born from stones. It happens because Zeus drowns all the clay people made by Prometheus, and the only survivors of the flood are told they must repopulate the earth by throwing Ďthe motherís bones behind themí Ė and once they realise Zeus is referring to Gaia (mother earth), not their individual mothers, they throw the stones lying on Mount Olympus which take human form as they hit the earth. Our ancestors are then stone, not clay. We are meant to be more resistant to the evils released by PandoraÖ. The subject of the film is truly the quarry, and the band are a manifestation of one of the quarryís aspects. In The Living Stones, Cornwall (1953) Ithell Colquhoun says: In a profound sense... the structure of its rocks gives rise to the psychic life of the land: granite, serpentine, slate, sandstone, limestone, chalk and the rest each have their special personality dependent on the age in which they were laid down, each being co-existent with a special phase of the earth-spiritís manifestation. (p. 46) This attitude does not seem fanciful in Cornwall, where Iím surrounded by natural tors and pagan megaliths. The relation of the human to the gabbro stone in the Quarry is very present as the quarry may well re-open. This is a recent chapter in the relationship between rock and community, itís not at all a closed book.

The geology of the quarry is really important to the film, can you tell us a bit about that? Iíll have to re-tell what Robin Shail the geologist explained to me Ė I might not remember all the details, but the broad facts are that the gabbro in Dean Quarry is the floor of the Rheic sea. 400 million years ago this sea was subducted and disappeared, although eventually the tectonic plates buckled and a tiny bit of that sea floor heaved back to the surface. Thatís Dean Quarry. After I heard that I thought about the old bones of the land.

Can you tell us a bit about the proposal to reopen the quarry? Shire Oak propose to reopen the quarry and use the stone to create the tidal energy lagoon in Swansea Bay. I thought that would make the project difficult because the owner would have to agree to stop works to allow us to film. They still havenít started work even now, because the permission to do the enabling works was put on hold when a community group named Campaign Against Dean Superquarry (CADS) took them to court. Cornwall Council granted the enabling works but they shouldn't have because they didnít have an up-to-date environmental impact survey. Since I first went into the quarry in 2011, all thatís happened is that a large perimeter fence has gone up severing the SW Coast path and the sea from the main quarry Ė that has happened since we filmed, so the quarry doesnít look now as it did a year ago when there were diggers and lorries there but not really mining machinery. By 2011 the crushing machinery for making aggregates had already been broken up, though on Google Earth all the equipment is still shown there as it used to be. Itís not updated.

Because thatís from 2005 when it was a working quarry? Yes, although they stopped working, they didnít dismantle all the equipment straight away. They say the new fence is a safety feature. Itís about visible structures of authority. The band members are divided over whether it would be a good idea to re-open the quarry. Many of them feel itís their heritage and should continue as a working quarry, and want to see those jobs open up. Others think it simply means permanent damage with no community gain... if it opens it will totally change the landscape here. The film does not subscribe to either side of this feeling - its focus is the intense relationship between this body of people and this body of rock, which is political, but indirect.

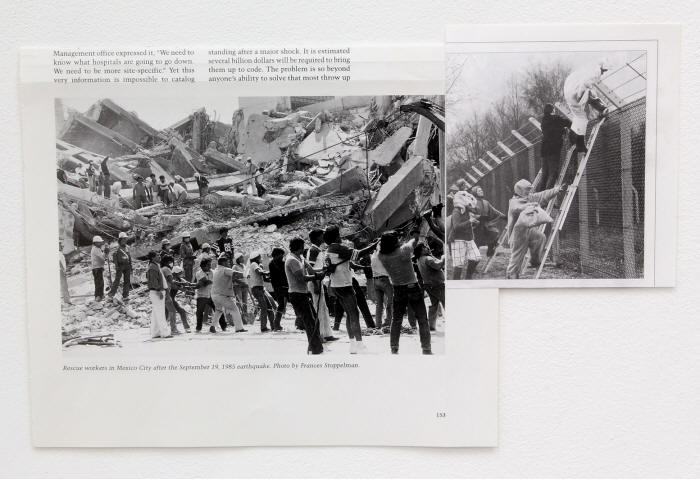

Thereís a sense of ritual in the piece that has a natural link to protest, which is interesting given the current tensions around the site, but then the music, the musicians, the imagery is actually really exquisite and special, it is a celebration of the quarry in some form...it almost humanises it. I agree - when you see the shots in the film of all the band members in the quarry, it is like an occupation; an occupation by the community of that site as if to hold it Ė as might have been seen at Twyford Down and the other 80ís road protests. At the same time, in the film theyíre working where they belong. If it was just wilderness, they wouldnít belong there. Itís complex, and I've been very conscious to have it between one thing and another. Thatís always the most interesting place to be anyway. Iím not interested in making a protest film. You have to be careful and respectful to work in these places. And Iím aware of a certain sense of respect or a certain sense of belonging. I donít live in St Keverne but I do live here. You couldnít possibly make this film if you were living in London, because it's so sensitive, and also because the work to really be present here and to listen properly is very slow. But I think itís good I donít actually live there because it would be awful, even if I lived in Coverack. You can be too close or too far and I feel like Iím just about right. All of my work using images of road protests (eg 'Up and Over' picture above), or the maidens in the circle is all in my mind in the film, but not explicitÖ

And the mood is not like that...there is no need for that kind of spirit there, the way the space is inhabited is very neutral and the film really feels like your work, it has that kind of visual language. To move from the found still imagery that I generally work with into making my own imagery felt like a significant shift for me because Iím used to editing and managing pre-existing formal visual structures. Editing in moving image is assemblage just the same, but it was an oddly unpinned sort of feeling to stage my own images. It was also strange to be able to play with time as a dimension. Given that all my work seems to concern itself with time Iím amazed that I have not done this before. Maybe itís because I enjoy my autonomy and a film like this needs a high level of collaboration and trust between people who are very dedicated and good at what they do, so I was worried that managing it would be very stressful. But filming itself was genuinely fun; very smooth and good-humoured with a festive atmosphere. I kept wondering when something would go wrong and it didnít. I really enjoyed it Ė we all did. I was quite scared of editing the film by myself, as everyone seems to work with an editor, and I knew I didnít want to do that as I am a studio artist not a film-maker. I like to work alone. But in fact it was fine to treat it rather like another collage work, and the film rather fell together by itself, as all good work does. It formed itself in front of me. I think it does confront what I hoped it would; the potency of that land. The potency of the really astonishing and passionate music Gareth composed for the band didnít conflict with the formal way I usually work. When I watch the film I feel really absorbed by it, even me whoís been watching it for months and months and months, again and again. But it does flatten you against the wall a bit. Iíve had to work hard to strip things away, to pull in spaces. Iíve found that really difficult. In my work generally there arenít any spaces; when I push two images through each other it results in something dense and compressed. Which I realised recently is something I like about motorbikes; when you accelerate you experience physical compression, like a push in the chest, or a hand all round you pressing you down. Maybe on a motorbike you just feel velocity better than gravity shows it to you. I really love it. And the film is like that, but it was a bit too much, even for meÖ.Iíve had to fight to make it release and open out.

How did the music come about? Gareth wrote a score in five movements but Iíve only used four in the film. I dropped a movement when I started to edit because it was too driving for the imagery. Each movement has its own visual language - so for instance the third movement only focuses on the band and the way they play, whereas the end is very solitary and, sort of, emptied outÖ

And how did the process of coming to the site work with the band? Were there rehearsals? They rehearsed the music that Gareth wrote for them, that was it. Theyíre not acting in the film. They already know how to stand and play. The boys at the beginning have great presence because theyíre only being asked to do what they do all the time. I just asked them to stand in a certain spot and direct their gaze in the way I wanted, then just play their instrument from when I say go until I say stop.

When you were creating the work was there an audience in mind or a location? What is its end point from that perspective? I am used to showing in commercial and non-commercial galleries internationally and I am generally interested in moving into a different area and for it to be in a cinema space. Also Iíve made a film thatís very intense, in a way that cinema is intense Ė itís dark and thereís just you and the huge screen. Cinema is a very emotional experience. Iíve only recently realised that we could live score it, like a silent film, and have it projected in a quarry with the band playing live. It would need some practice because Gareth would have to conduct. It would be very strange to see all the people in the film playing, mirroring each other with this film. I think that could be amazing. But I donít know - itís one of those events that would take a decent amount of planning to do wellÖ.

There are some strange effects in the film, like when the shots of the rock split into green and red... That came about from my initial desire to feel sculptural in the quarry, (itís not really 3D but we recognise the cue) and then it relates to the story of Deucalion and Pyrrah - the stones trying to transform themselves into humans or resolve themselves in some way. Itís a suggestion that the quarry might somehow animate, or that these rocks might be super-charged. In the edit it began to relate to a twitch on the drone-shot that goes out into the sea over the grading bins, which is not an effect. It is in the footage because the droneís camera is trying to stabilise the recorded image and it canít stabilise the sea - so it just freaks out! Those accidental moments are wonderful because I feel thereís an energy thatís just not very controlled. The media canít cope with the environment. I had made the 3D effect before I realised the drone footage was de-stabilised. It was a happy co-incidence.

Itís almost another character, another energy, another presence or entity in the work. Itís that feeling that the landscape has this energy or potency that is not rational, which Ithell Colquhoun gestures at. There is an energy at work and that we donít understand and weíre not working with. Recently Iíve been reading Annie Dillard. She writes: Ďnow the whole world seems not-holy. We have drained the light from the boughs in the sacred groves and snuffed it in the high places and by the banks of sacred streams.í Weíve obliterated all of these mythic spaces because we find them very threatening, I wanted some of that to leak out in the film, so a lot of the effects are about that for me. But then there are also these vary rational geometries within the film. There is a triad of glass models (picture above) which speaks to a triad of adult players from the band. I have staged them precisely as Barbara Hepworth arranges the three elements of her 1973 work ĎMagic Stonesí. The glass forms are mid-century teaching models of the seven crystal systems, which I borrowed from Camborne School of Mines. The packing systems of the crystal systems they represent create the kaleidoscope of colours that you see in the magnified gabbro shots. In the film there is a view of a gabbro slide through a microscope at x5, (thatís a section of the rock about 4mm across) as a polarising filter is pulled across the lens to position one then two. A geologist can read the colour changes and by them understand the mineral composition of the stone. Colour changes reveal which crystal systems are present. The bright colours happen because of the crystal packing of the minerals comprising the gabbro. I was very surprised to find that stone is analysed visually - through these packing systems. Itís a standard geological analysis of gabbro; it is beautiful in two ways. As every shot of the film does, the glass models relate to the geology of this specific place in Dean Quarry and to the microscope imagery. Everything is linked. The moon even Ė which gives a scale in opposition to the microscope imagery. Again that was a happenstance on the day of filming. We set up the shot with Caroline walking and there was the moon. Perfect Ė another scale Ė another sense of time. Another lump of rock hanging in the air.

The tempo and feeling of the film changes towards the end, suddenly youíre following the actions of an individual. Yes. The film closes with a more conventionally filmic language. I wanted to end with a feeling of giving oneself up to the quarry. Something abandoned or opened out, something very immediate and physical. Watching the bandsman lying in the cold stagnant water, feeling it soaking into his hair and his beautiful uniform - I wanted that very physical connection to the quarry to end the film. I think as a film itís constantly pushing through visual languages, different scopic regimes from different conversations, so the filmic can just be there as another one. Itís just a very dense tapestry. There are many structural principles I worked with in the edit, like lightness and weight. Some shots (like the drones) are weightless, as in myths people commonly fly across worlds and times. Other shots are very heavy Ė as the gabbro is so heavy. I was just very aware of that and for example flatness and depth as well as the scales of time and size shifting all the time.

When we first watched the work there was a sense of familiarity, the site, the area, the sound, but if someoneís watching this in London or Vienna do you think the reaction, the experience will be different? Iím finding that, actually, extreme localism travels really well. I was surprised that people responded really strongly when my sculpture Tol (picture above) was shown in Hong Kong. I suppose that a community choir or band is common to many cultures. A strong sense of community and relation to the land is probably quite 'travelable'. Iíd be interested to find out Ö

Well, because it almost becomes otherworldly... Thank you. Also itís so specific, itís not trying to talk about every quarry, or every group of people and where they live. I have focused very narrowly on this very specific site - I guess thatís what you understand Ė in the extreme focus you can come through to find something that can be shared. * Annie Dillard ĎTeaching a Stone to Talkí p69 1984 Pan books

All images are screenshots from 'The Mothers Bones' unless noted otherwise in the text. See 'webprojects' for 'Double Brass' 2014 and 2015.

|

|

|