|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

David Tremlett on beatniks, the Royal College and early British Conceptual art David Tremlett is a pioneering first-generation conceptual artist. Having grown up in Cornwall, he left the Royal College of Art in 1969 and within a couple of years was exhibiting throughout Europe and America, including shows at MOMA in New York and Documenta in Germany. Phone interview by Rupert White.

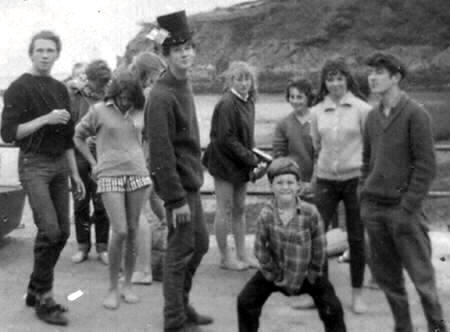

We were near St Mewan – between St Austell and Sticker. There was a farm there that my father and mother ran called Bosinver Farm. They came there at the end of the war. My mother was from Falmouth and my father had extensive Cornish connections. I was born in Kent and was brought down about 6 months later. My father was also a mining engineer and he reopened an old tin mine near Polgooth, which was our closest village and where I used to play as a kid – there and Mevagissey(picture right: with top hat at Portmellon near Mevagissey). The BBC have archive footage of my father getting this mineshaft going. Mevagissey, the fishing village, was a rather bohemian place then wasn't it? Colin Wilson was the most well known writer in the area. Then there was Lionel Miskin who introduced me to Falmouth Art School. My father, at the time, was trying to get me to join the Navy. He’d say ‘it's all about getting a job boy’! There were a few beatnik-types who lived in Heligan Woods, in the cottages there. There was an artist who lived there called Ivor De Courcy, then in Mevagissey itself there was Lionel Miskin and a potter, Bernard Moss. According to Ralph McTell, various folk musicians also stayed in Heligan Woods. John Furnival the poet also lived there for a while... My connection with Heligan was through a girl I met at St Austell Grammar – Bridget Gilbert who went on to work in the theatre at Stratford on Avon. She was the long-term partner of actor Ian Holm (Bilbo Baggins) and she was with the brother of Jane Birkin (singer) for a long time. She now runs a charity in Nairobi. Heligan was where I met Martin Val Baker. Martin's father was a writer (Denys Val Baker) and in 1962 Martin came up from St Ives with some friends from Penzance – Lew and Jonathan Baker. Their father was a writer too... Yes, and the Gilberts' father was also a writer – he wrote screenplays for the BBC. Colin Wilson was living in Gorran Haven. I met him several times as a 16-17 year old. He was this older, more famous writer. I 'd have met him through the Gilberts and De Courcy. De Courcy's wife, Brenda, still lives there, in that small valley. Some strange people would end up there. Michael Marks of Marks and Spencer was off his head! I have this recollection of walking along a path once, and seeing this man with his head in the hedge, talking to it somehow. Apparently he thought he communicate with crane flies, so he'd be there talking away in the hedges! Sounds like it was a very formative period for you. Was it? Definitely. I was never really a true beatnik. I was the son of a middle class farmer. But these people changed me. I'd never read Dostoevsky or Pushkin until I met that group. I ended reading things I might never have, including Colin Wilson's 'The Outsider'. The Outsider was influential for many young people at the time. Yes. I even noticed it in David Bowie's reading list. It taught you about all these people who were outside society. Dostoevsky's 'Crime and Punishment' was a good example: the character being such a stranger to society. The Outsider also introduced Existentialism to a lot of English people... I didn't understand what Existentialism meant until much later. But it was a beginning, when you became political and joined 'ban the bomb' CND marches. You went on a few of the Aldermaston marches, and Martin has even written about you being arrested on one of the Committee of 100 marches (picture above: Aldermaston march 1965. DT is wearing the leather jacket). Sounds like you became quite immersed in the beat lifesyle.

And some of you would camp out in the woods in Heligan? Not me so much – I just lived round the corner – and my parents expected me to come home! It tended to be Martin's group who came up from Penzance to stay overnight in the camp, putting aspirin in their cigarettes to try and get high. I was impressed by all that. I liked the fact that their parents obviously didn’t give a damn if they spent days or week away from home! How did visual art become part of your life? St Austell grammar didn’t have an art O-level but they had an art class and I used to enjoy drawing. And I used to carve blocks of wood that my Dad would have around. I used to make faces and various funny objects. I had no intention of going to art college, and in fact I had no intention of higher education because my parents had wanted me to get a job. Miskin said ‘let’s have a look at what you’ve done at home’. I’d been copying Michaelangelo’s sculptures out of books, that sort of thing. I showed him and he said ‘put it into a folder, send it down to Falmouth, and come and have an interview’. So I drove on my scooter to Falmouth, and I got on the course. It meant that Cornwall would pay for the lot. They'd pay my fees, digs and food. My parents were thoroughly pleased. My father saw this as an opportunity to get rid of the farm and go to Australia, because they thought that I’d ‘found my path’.

And Miskin was a sculptor? No, Miskin was a painter. I always liked Lionel a lot. He was a mystic. Oskar Kokoschka and Chagall-kind of influence. He was a clever and passionate man, and he was an artist in every sense of the word, and he lived the life. But I wouldn’t say he influenced me. I was always sceptical of bohemianism. I was quite disciplined, I had a discipline in me, that meant I had a slight suspicion of bohemianism. That's what Lionel represented, much though I loved the man. I was more influenced by Ray Exworth who was a tough little cookie. He’d been at the Royal College and was extremely hard-working and disciplined. Frighteningly so. He was the one that told me when I was quite young that I was dreadful: ‘Tremlett you're shit. You shouldn’t even be at art school’, sort of thing. Actually the other tutor in Falmouth, Frances Hewlett – who was really good fun – would always say don' t listen to Ray Exworth... Of course it would have been a small college then, with only 30 or 40 people in your year? Or less – maybe 25, and we all had to quit Falmouth after one year. They didn't do the DipAD course, so we all had to leave. I applied to Birmingham, painting, and didn’t get in, but did get accepted into sculpture. Because I’d been told I was so dreadfully useless I couldn’t believe it! My parents left for Australia at around the time I started at Birmingham, but because I still had friends like Martin and a guy called Terry Pascoe, in Cornwall, I would often come down to stay. So in 1965 I spent the summer selling deckchairs on Porthminster beach in St Ives (picture below right). Later Terry helped me a few times as an assistant, mainly in France. Talking of St Ives, when did you first became aware of the art colony and its artists, and what did it mean to you? I didn’t see a lot of it. At Falmouth we’d have Terry Frost coming in, and Patrick Heron occasionally. We went to visit Barbara Hepworth, and I remember visiting her studio and seeing her there. St Ives was the haven for all artists, then, but I wasn't very impressed. It was something about the lifestyle. There seemed to be a lot of going into pubs and getting drunk – a post-Dylan Thomas thing – which I was suspicious of. I felt a need to avoid this cosy, comfy, pally thing... Were you also suspicious of abstract art? Not really. Ray Exworth encouraged a lot of life drawing, but I'd read about the Russian Constructivists at Falmouth, and Mondrian, and I liked the geometry. I liked the mathematics in it. I was never convinced by sentimentalism and story-telling in art. It was this odd thing about being disciplined and being on your own that fascinated me. I have children, and a family, and I meet people all over the world, but the reality is that I am on my own when it comes to my work. And I feel happier being on my own, in a disciplined structure. This attitude must have come out of Cornwall and that fuzzy intellectual existentialist-beatnik period, that grounded me very well for the later 60's and 70's... Do you want to say something about Birmingham? Birmingham was a shock. It was this depressed city in decline, and the whole thing was pretty miserable. It was a good lesson in how to adapt to a completely different environment. And I felt seriously on my own. I didn't know anybody, and I didn't know the culture: I hadn't seen a prostitute or a street drinker in my life...

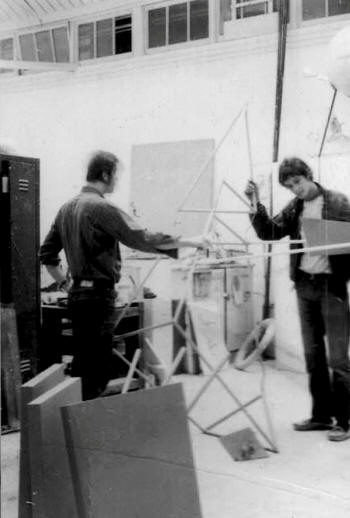

The RCA (picture left facing forward) was one step further into the abyss. It was full of highly toffee-nosed people – in my view – and I was coming in as a hick from the country, to some degree. There was a chap there called Peter Atkins and he was teaching at St Martin's. He was interested in your ideas not in what you were physically doing, and that helped me a lot, whereas your Bernard Meadows and all that 'post-Henry Moore lot' were all hard workers, but I did n't get much from them. Peter Atkins changed his surname to Kardia. He was the one person who was encouraging to Gilbert & George and Hamish Fulton and Richard Long. He was encouraging as a character. He was not a practicing artist, he was more of a theoretician. He was at St Martin's most of the time, but he got brought into the Royal College because it was the beginning of that conceptual art period. Nobody really knew that much about it at the time, but he had some interesting ideas, post-Fluxus and all that. He had a good knowledge of Fluxus and post-Fluxus, but people like Meadows, and Clatworthy, and Brown, and Bryan Kneale didn’t have a clue. They made objects and made them well, or badly, and tried to sell them, whereas the Kardias of the world were trying to find the new generation of artists. Can you clarify the dates that you were at the RCA? This is 67/68/69. I left in 1969. Are you saying that post-Fluxus conceptual art wasn't very visible then? There was little being shown in the galleries. The dominant influence at the Royal College was still Peter Blake and David Hockney. All the pop artists were like the king pins. Blake, and I think Hockney, were coming in as teachers. I think I saw the odd magazine showing Joseph Beuys or Kaprow or Fluxus, which was nothing whatsoever with what the RCA was teaching. Which magazines? Studio International? Yes. And Art International and Art Forum. What I think I had in common with people like Gilbert & George was a sense of rebellion. Perhaps it was the old beatnik thing again. I found the RCA very traditional. It wasn’t very free. You were free to do what you wanted, but only within particular parameters. So those that got the gold medals and the prizes were the ones doing rather boring bog-standard stuff – very competent but I've not heard of or seen any of them since I left. Presumably they became teachers of some sort.

So my diploma show was put on, and it was all to do with greasy mechanics and strange photographs, and it was clearly influenced by Fluxus and looking at Beuys, and in fact I'd made a trip to Germany because of the influence of German artists then. So it was partly performance and photography based? Yes. Photography and using yourself in the work. But I was also making objects. The very first show I had was with Grabowski in Sloane Square (picture above right). He was before Lisson and Nigel Greenwood. He came to the RCA and he saw what I'd been making. So for example I'd made this column of bricks, with nails and barbed wire. He offered me a show which was very well received. People like Richard Cork wrote reviews, and Peter Kardia wrote this forward for me. It was my first solo exhibition. I sold one thing to Mr Grabowski, and Nigel Greenwood came to that exhibition and said would I like to work with him, and he stole me in a way, because after I’d visited him to see what he was doing, I said 'absolutely'. You were also in the Young Contemporaries (now New Contemporaries) at around the same time...

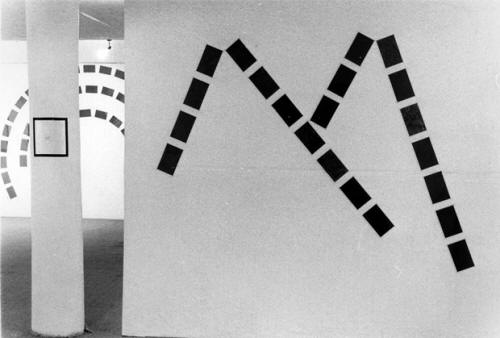

I got to know Gilbert & George via the Nigel Greenwood Gallery, which is where they first did 'Underneath the Arches'. Later they were my best men when I first got married (picture left). Then I went to Germany a bit more, and I did a show with Konrad Fischer in Dusseldorf. Jenny Licht worked at MOMA in New York and there was a set of shows called the Project Series, and she came over with Kynaston McShine who later became the director and they asked me to do one of these interesting forum small shows (picture below right and in 'features'). There were lots over a number of years, and it was very much part of early Conceptual Art when they were trying to bring over German and French artists, and people like Richard Long and Barry Flanagan from the UK. And you were interviewed for the very hip Avalanche magazine. Yes. And I found myself appearing in Avalanche in different ways. Willoughby Sharp, the editor, came over to England. And through that connection I met Michael Heizer and Carl Andre and all these people. I did the interview in Earls Court. If you look at Avalanche, Willoughby Sharp’s got very long hair, and he used to be a very eccentric character. He was Brit in fact. He was sniffing cocaine, which I didn't know anything about at the time. So he'd bought me a bottle of whisky, and he sniffed cocaine, and he wrote this appalling interview. I hated it – I've never liked it – it was just waffle. Why? Did he not ask the right questions? He was endlessly looking for crazy, weird characters. He was a big fan of Vito Acconci, who did a lot of strange things, and he loved Joseph Beuys – he did the first interview of Beuys for Art Forum in the very early 70's in fact – so he was always after that angle. And so my being under a railway arch, and hitchhiking to Australia and so on, he liked all that and tried to create a character out of it, but I never really liked it. Looking at those magazines it's striking that Conceptual Art became an international movement very quickly.

Did any aspects of this pop culture affect you? Did you have much contact with musicians or designers for example?

In the 70's I

knew Laurie Anderson quite well, and I met Philip Glass and Steve Reich.

One of my old friends is John Dunbar who used to run Indica, and I still

see him occasionally. He was married to Marianne Faithful, and so there

was that crossover with pop. And I was at Birmingham with Christine

McVie, of Fleetwood Mac. But that was about it.

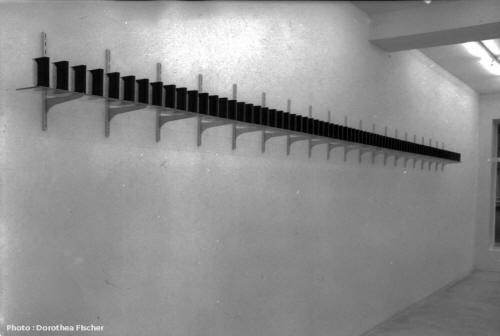

I believe there was a work called 'Green' that went with it? For 'Green' I took a slide photo in every county. Green I showed in the MOMA in Oxford when Nick Serota was running it. It was shown as slides playing on a carousel. How did the wall drawing develop out of these earlier works? At the point I gave up the studio in '71, because I had no money left, there was a period when working on a budget became necessary. I'd put an exhibition in a small suitcase and go somewhere, and put it on the wall. The cassettes were a bigger object, but most of the time I used to use these filing cards that were massaged with graphite which I'd spread out over the wall (picture below right: Oxford MOMA, 1974). This is something that should be shown in the Tate this spring. They were really the precursor to the wall drawings. I realised I could do it without truckloads of stuff, just with my hands and a few pencils. I had a tiny little place in London, before I moved to this tiny little place in Hertfordshire so I never had any space, but felt as if I had the whole world to work in. That's where the idea of making wall drawings came from. And its not unique to me. Plenty of good artists have done it. But behind this remember I did 7 years as a sculptor so I've always thought of it as making something, or constructing something. Its not about painting. Its not an illusion, its about making something on a surface. Its about physically making something. And it's sculptural because you're creating an environment My particular love now is the use of the architecture. So you're crawling up wall and across a ceiling and out the doorway and it becomes thoroughly three dimensional.

That was work on paper. I 'd been travelling in the North of Europe, and North America and I was doing these little line drawings. I did a book with Nigel Greenwood called 'Some Places to Visit', which are simple line drawings. The Tate have this piece called 'The Cards' which is like musical hieroglyphics describing a sort of landscape, and the Newlyn drawings were similar but had much straighter, stricter lines. It was always about a finding a language. The cassettes are a sort of hieroglyph or language for a landscape. There was always this link between different sets of objects, and cards, and rooms. It was serial. It went from one to two to three to four. Landscape is often present in your work Landscape was always there. Its the passage of location and what goes on in these different locations if you're going from one place to another, from one town to another. It was always the passage that I was interested in. There's a language and a structure to it. The different forms I use are a description of time and passage. I employ them inside buildings these days. It's about that movement, and creating a structure with materials like pastel rubbed on by hand. What you're describing is rather abstract and speculative, the antithesis of the Pop Art we've been talking about. Pop Art is nearly all illustration. Its a clever illustration, in my view, which is obviously pictorial and realistic, and it describes the subject as most people like to see it. And what's interesting today, is that artists are asked to describe what their work is and they come out clearly and say what its all about. Its like everyone understands art now, and they all go to Tate Modern and they love it! Part of the mystery of art has disappeared. Art has become another product, despite all our efforts at disguising it, and being awkward, and not talking about it, and everything. You very rarely hear an artist these days declining a question. I never did interviews in the past. I'm old enough now to have a rough idea, but I still don’t have any clear ideas. The subject matter to me is still very vague. I spend every hour of the day trying to make it less vague!

If I was going to say 'thankyou' to any country it would have to be Italy. Italy has been super-generous to me and I love the place. I keep returning there. This character called Cerreto runs a wine company making the best Barolo in the region. He sponsored a group show and I was asked to do a work in an old castle in Barolo and he put me up. One day he said 'I’ve got this little chapel sitting up on the hillside in the middle of the vineyards and I park my tractor in it'. I had a look and I thought it's in a fabulous position, and we had a talk and I said, even though its been deconsecrated, 'Is there any way we could return it to the idea of a chapel?' Sol was around at the time and I'd known him since the early 70's and we often met up in Italy. I said to Sol 'I' ve found this fantastic little place, are you interested in doing a collaboration?' We'd never collaborated but we'd been in endless exhibitions together, and we were both doing quite substantial wall works. He said 'yeh, but David I don't think we should touch because then we're gonna fight...' He was more experienced on the outside of buildings, so he went outside and I went inside. The floors I made in marble and the windows were made by Murano and I made a costume for the priest with Missoni. It took Sol 2 or 3 months to get his outside done, and it took me 6 to 8 weeks with a couple of assistants. And he didn’t pay us very much – we got a few bob in our pockets – but he did then say I 'd like to give you one bottle of Barolo top end wine every week 'til the rest of your life. Sounds good. And what projects have you now got coming up? I’m doing a new chapel in the same part of the world this year. It 's the exterior again up on a hill and I 've gone for a for a very strange, interesting work on the whole of the outside which has now been passed and everyone is up for it. I've got a big project in Munich coming up, and a massive one in London. I'm not allowed to say where, but you should hear about it at the end of the year!

David Tremlett's website: http://www.davidtremlett.com/ Martin Val Baker's archive http://www.rainydaygallery.co.uk/musicarchive.html

|

|

|

Around

the middle of my 3rd year my grand-dad died down in St Austell and he

left me a £1000 and a pocket watch. With that £1000 I decided I was

going to get a studio. So I went out and I found a railway arch down in

Camberwell. It was £25 a week, and I decided to rent it. I told Bernard

Meadows, and he said 'that's OK you just have to come back with some

work and show us what you're doing'. But I didn't go back for about 6

months, at which point I had a letter saying that if I didn't show

something they would write to Cornwall, and Cornwall would ask for my

grant back.

Around

the middle of my 3rd year my grand-dad died down in St Austell and he

left me a £1000 and a pocket watch. With that £1000 I decided I was

going to get a studio. So I went out and I found a railway arch down in

Camberwell. It was £25 a week, and I decided to rent it. I told Bernard

Meadows, and he said 'that's OK you just have to come back with some

work and show us what you're doing'. But I didn't go back for about 6

months, at which point I had a letter saying that if I didn't show

something they would write to Cornwall, and Cornwall would ask for my

grant back.