|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

Michael Bird on Bryan Wynter and St Ives Michael Bird is the author of a new monograph on the celebrated abstract painter

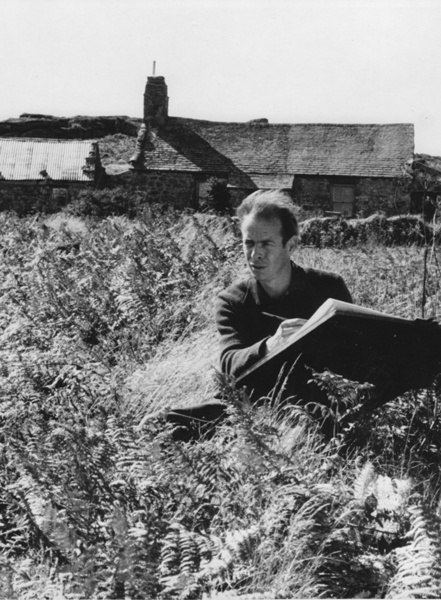

RW: How did you perform the research for your latest book, the monograph on Bryan Wynter? Does Wynter still have relatives and friends in Cornwall who were able to help? MB: Wynter was only 59 when he died in 1975, and he’d lived for many years in Cornwall, first on the moors near Zennor and then on the south coast near St Buryan, so there are quite a few people around who remember him. In fact, I had a strong impression from talking to people that he is still missed. He evidently had great charm and humour, and women especially seem to remember his voice – a resonant, seductive bass. I interviewed some of his friends and associates from the post-war art world. Paul Feiler, for example, was a contemporary of Wynter’s at the Slade and Alan Bowness was an influential advocate of his abstract painting. I also spoke to family members; the absolutely crucial contribution here was Monica Wynter’s. She met Bryan at Corsham in the early 1950s, when she was a student and he was teaching there, and they married a few years later.

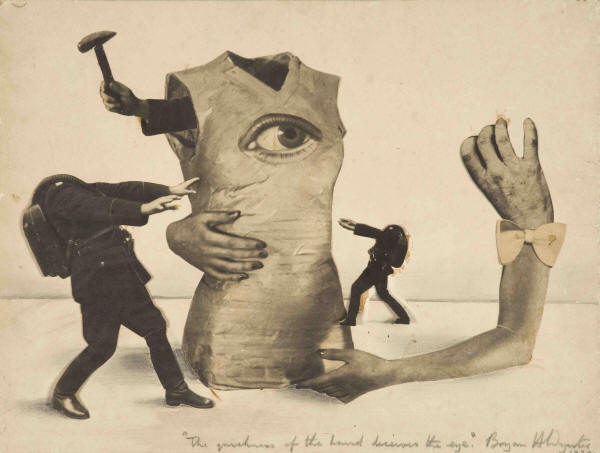

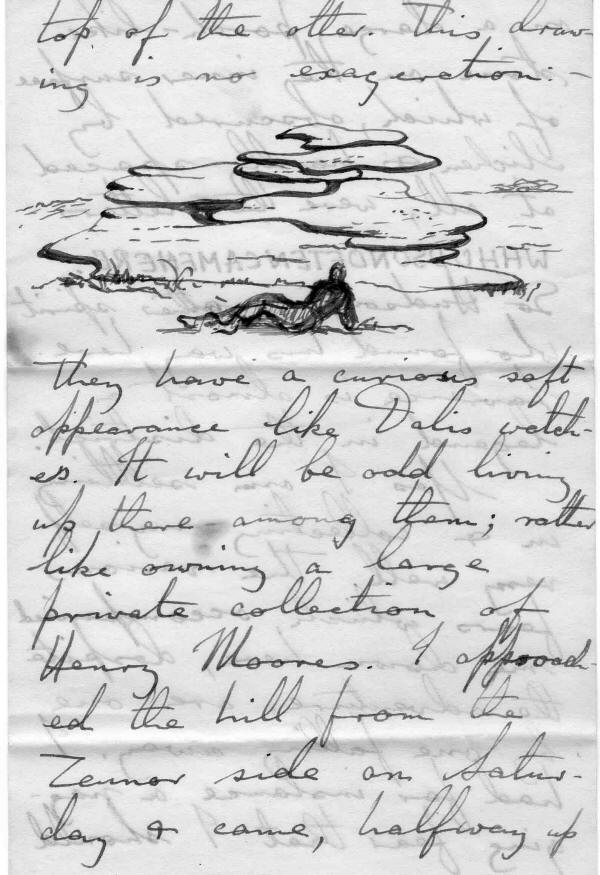

I don’t try to interpret art in biographical terms, but biographical details often give me points of entry to the work, a sense of what the whole process is about for an artist. I read Wynter’s notebooks, his dream diary, his 240 or so surviving letters to his girlfriend Hedy Hoffmann, which provide a lot of insight into his life and art during the early years of his career. There’s an imaginative consistency to his thinking, a kind of poetic logic that runs right through from his student days to his final works. Wynter’s output is diverse – he travelled from Surrealism to Neo-Romanticism to abstract expressionism, kinetics and other experiments – all of which made finding, and following, the connecting threads a important part of the book.

RW: When did Wynter first come to Cornwall? How old was he and did he already have a reputation as an artist? MB: Wynter arrived in Cornwall from Oxford in June 1945, soon after the end of the war in Europe. He had no plan to join an artistic community – St Ives, as far as he knew, was all about traditional marine and landscape art, which he found boring. He simply wanted to leave the restrictions and repressions of wartime behind, to get away and work out what he was going to do next. He knew Cornwall from family holidays in the 1930s, and probably associated it with positive, carefree experiences. Despite the difficulties of pursuing his art during the war, Wynter, who was now 29, had already started to make a reputation. His work was profiled in the journal Counterpoint, which also featured Paul Nash and Eileen Agar. Wynter was supposedly the face of a new generation that was going to develop Surrealism into something more humane and mature. This piece led to the offer of a show at the Redfern Gallery, which eventually took place in 1947. So his career had been launched, although this was the dawn of the original Austerity era and not a great time to make a living as an artist.

RW: Did he quickly find a peer group in Cornwall? How important was the Crypt Group to him in the early years? MB: Soon after arriving, Wynter met Sven Berlin, who I think introduced him to Lanyon and Wells. These four artists, with the letterpress printer Guido Morris, staged the first Crypt Group show in September 1946. After the war years, which had almost eaten up their youth, they were all desperate to exhibit, and they put pretty much everything they could into the show from the previous six or seven years. Outside that particular exhibition (later Crypt Group shows had a different line-up), I don’t think the group in itself had great importance for him – Wynter never felt comfortable with joining groups or teams of any kind. The big thing for him in autumn 1946 was his discovery of Braque, who was being shown in London. Of the other artists, Berlin was a good friend but Wynter found Lanyon’s work more interesting. Wells was a quiet man whose affinity was with Hepworth and Nicholson’s brand of ‘Constructive’ abstract art. Altogether it was a group without much of a shared agenda beyond getting shown and being seen to be modern.

RW: How did Wynter relate to Hepworth and Nicholson? MB: Wynter’s decision to go to art school – bitterly opposed by his father – was partly inspired by the 1936 Surrealist show in London. He really wasn’t interested in the kind of abstract art practised by Hepworth and Nicholson, which in the 1930s had been the rival tendency to Surrealism. And this was surely the exciting thing about St Ives in the late 1940s and 1950s: there never was a ‘St Ives group’ with a shared programme but instead a gathering of artists who had come from different backgrounds, personally, artistically and ideologically. That was what made the place spark. Wynter was unusual in being a British artist who didn’t simply adopt Surrealist motifs but systematically employed automatist practices. In that respect, other artists around St Ives had little to teach him. I’d say, though, that he was influenced by Lanyon for a limited time – around 1952–54, when they were both teaching at Corsham – but after that their paths diverge again.

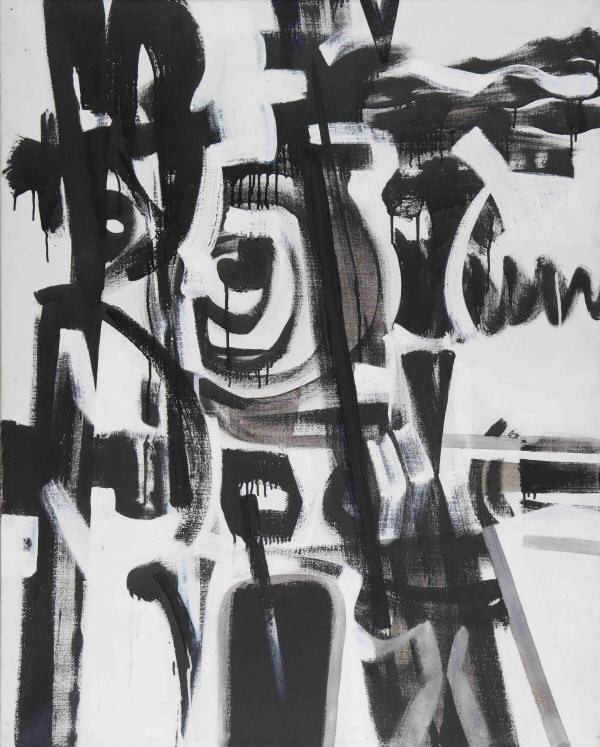

RW: At what stage did he move to being a completely abstract artist? How did this come about? MB: The abstract moment for Wynter can be pinpointed quite precisely. After three or four years of inconclusive experimentation, in January 1956 he began a great series of abstract paintings that critics almost immediately saw as a British version of what the New York School had been doing. In fact, you can see how these works, which seem so different from what Wynter had been producing before, developed out of his Surrealist-inspired interest in psychoanalysis and automatism, just as had happened with Pollock. Did Wynter begin the first of these paintings, The Interior, before or after he’d seen the Abstract Expressionist room at the Tate that same month? We can’t be sure, but there’s a strong case to be made for a parallel development, independent of New York School influence in its early stages. As with other British painters, such as Heron, whose work became abstract in the early 1950s, there were many factors at work. They’d all been looking at De Stael, Soulages and the French tachiste painters. For Wynter, his experiences with mescaline, to which he’d been introduced around 1954, were also formative.

RW: What can you say about his personality? He has a reputation as being more 'bohemian' than some of the other St Ives artists. I think this is possibly because he wasn’t as comfortably off as the likes of Lanyon and Heron who, so I understand, had private means. MB: Wynter was an independent thinker and a determined individualist – these qualities were the bedrock of his personality. The extremely basic cottage and studio on the high moors above Zennor, called the Carn, where he lived from 1945 to 1964, was a romantic, bohemian location – the exact opposite of the well-upholstered, middle-class milieu of his boyhood. At the same time, Wynter liked to maintain a certain orderliness in his domestic surroundings and workplace. He wrote scathingly about the posturing bohemianism of Soho’s ‘urban gypsies’. Wynter’s grandfather had made a fortune from the laundry business he founded in the 1890s and lived in a huge house in London where he once gave a garden party for nine hundred guests. Wynter broke away from this kind of life, but some of the wealth occasionally came his way – enough to tide him over the thin times, at least. You are right that Lanyon and Heron’s families were also well-off, as were Hilton’s and Barns-Graham’s. Things were very different for a working-class artist like Terry Frost, in ways I described in my previous book (The St Ives Artists: A Biography of Place and Time). When you think about it, the whole phenomenon of mid-twentieth-century ‘St Ives art’ rests on the availability of unearned income for several of the key players. There’s nothing unusual about this: throughout the twentieth-century, artists who sought to innovate often required some form of subsidy, whether from a rich patron, family wealth or the state. This is still part of the artistic economy of our own times.

RW: But there are also the IMOOS, and the experiments with mescaline and other drugs which suggest Wynter was something of a psychonaut, perhaps more interested than the others in going beyond art in order to explore alternative states of mind. MB: I like the idea of Wynter as a psychonaut. Very early on he spoke of art as a meeting place of inner and outer, and you can see much of his work in these terms – in the way, for example, in which the kinetic works he called IMOOS (Images Moving Out Onto Space) seem to reach out to, and around, the viewer. Huxley was a very influential writer for Wynter throughout his life, from his advocacy of principled non-violence in the 1930s through the mescaline experiences he described in The Doors of Perception in the 1950s. Wynter’s circle of artists and poets in Oxford during the war were all reading Freud and Jung, and he too wrote poetry and kept a dream diary for a while. It’s interesting how Wynter’s wide reading and cultural reference, and his literary as well as artistic intelligence inform his false starts as an artist as well as his great successes. The point was, he was always going somewhere – exploring, experimenting. His collages, landscape photography, drawing machines, kinetic constructions, kayaking maps – all these, and many other experiments and experiences, were part of what he saw as a process of preparation for painting. Today, when process is considered important in its own right, an artist could make a whole career out of any one of these aspects of Wynter’s practice.

|

|

|