|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

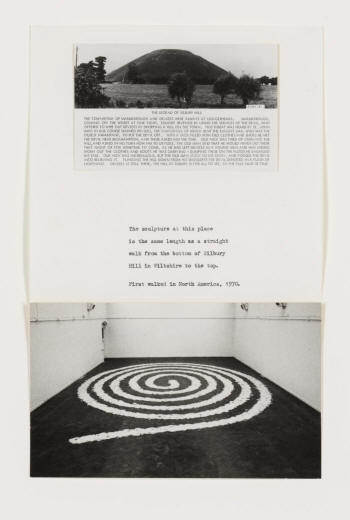

Michael Dames on The Silbury Treasure and 'in-and-out-of-the-soil' myth Michael Dames is a writer whose highly acclaimed book, 'The Silbury Treasure' (1976), suggests that man-made Silbury Hill is an image of the Great Goddess' pregnant womb, the rest of her reclining body being described by the surrounding moat, which despite now being filled with at least 10 feet of silt, still appears waterlogged at times. This theory and other revelations relating to Avebury, were subsequently picked up by pagans and feminist artists like Lucy Lippard and Monica Sjoo. Dames' most recent book is entitled 'Pagans Progress'.

My love is the landscape. Everything starts with that for me, whether its myth or paintings, or anything. I'm a 'ground-based' person.

So you taught yourself art-history?Yes, that's true. I was fortunate in Aylesbury , Buckinghamshire. The county library HQ was there, and there was a whole stream of art books just round the corner from where I was at school. And that's where I spent my spare time.

Did you grow up in Aylesbury? It was nearby, in the countryside, and I was very happy working on the land, earning money to take my girlfriend to the pictures, on Saturdays, and at harvest time, mucking out the cows and that sort of thing. I'd been living in this village since I was two, and I wanted to connect with what was going on there. And the most obvious thing was agriculture, so I was glad to join in.

Then you moved to Birmingham to go to University... I wanted to see lumps of Britain I hadn't encountered before, namely the industrial Midlands.

After this you landed a Geography teaching job in Manchester . How did you move more into art and art history?It was a two-tiered thing. I'd switched from teaching Geography, to teaching Art in the grammar school, so I'd already made that transition to the visual. My first one-person show was in Manchester. I had one in the Central Library and one in Gibb's Bookshop. The exhibitions gave me an extra incentive to gather my own thoughts together.

And were these landscape paintings? I was briefly intoxicated by the 'dark satanic mills'. I don't just mean mill buildings, but deep gullies cut in millstone grit, with weaving villages and textile villages stuck in the bottom of them. It was a total novelty to me, and I was enraptured by that. All the townships around Manchester had mill chimneys, which were all still working. Our youngest son in the back garden would be covered with large lumps of soot when we brought him in!

How were you then affected by the changes referred to now as the 'Swinging Sixties'?It was an exciting time. Colour supplements were bringing new ideas to students who didn't have to rely on the one tutor who they didn't like very much. There was a lot going on in London, and there was to-ing and fro-ing between staff in London and Sheffield. I was preoccupied with getting slide lectures together. I worked quite hard on presenting decent shows to students.

And so you were visiting London a lot? Yes, and I had a one person show at the Woodstock Gallery, London W1, in 1964.

Vaguely in touch. But I am by nature a rather solitary person; I don't tend to seek out groups, though actually when invited to them I do accept, as I did at Feminist conferences held in Greece, Bulgaria and Luxembourg, and at Ley Hunter moots in Avebury and Oxford.

What

has been your view on leys

and 'ley-theory'? I believe more firmly in sight lines than in ley lines. What the naked eye can see, who can split asunder ?

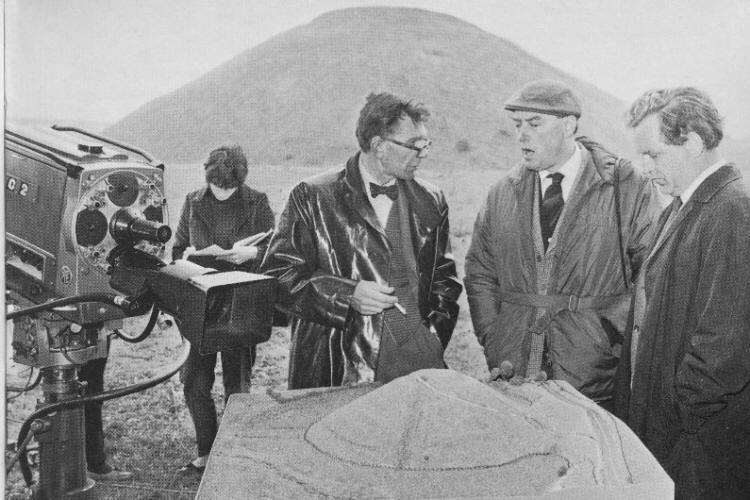

What specifically led up to your first book 'The Silbury Treasure'? I was teaching in Swindon College of Art

just as Richard Atkinson (above with TV crew)

was finishing

his dig into Silbury Hill. He dug an extra tunnel into it, and at that

time it was presumed that Silbury Hill was a Bronze Age hero's tomb. He

was desperately looking for golden treasures to prove his point. What he

did find on the very last day of the dig was an urn with a lid on, and

inside was a message saying the

urn was left here in 1849 by a previous excavator. So he was rather

chasing his own tail.

What he did find was that

ants in the interior mound could be dated to the Neolithic which was a

thousand years before he presumed the hill had

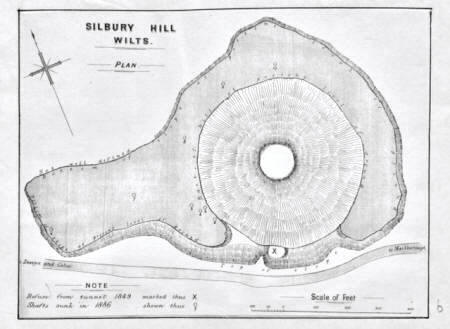

And then a stony silence fell on the subject. He lost interest. He'd found the wrong period. So I thought whats wrong with the Neolithic? And I realised that the Neolithic was a female-centred culture that started agriculture and brought it to Britain, and that its monuments might have reference to agriculture and to a female deity. So that's what got me going. I was glad then to move to Birmingham, because the libraries are so much better there. So I could follow up this flickering idea in detail, comparing it with other countries and the abundance of Neolithic figurines, usually squatting on the ground pregnant, so I thought: 'Hey! Silbury Hill is a Neolithic figurine!'. The moat is her body, though it's not very wet these days. So I presented Silbury as the monumental image of the presiding deity of that era, and of course this produced gasps of disgust and disbelief from Atkinson and his friends. But it was popular and I believe authentic.

There were a few people who wrote about the Goddess in the 40's and 50's. Robert Graves, and some of the Jungians for example.I don't claim to have invented the Neolithic or Goddess culture, but what surprised me was that 1960's archaeologist s were keen to prove how scientific they were. They weren't interested in imagery of any period, really. They certainly were n't interested in a culture that was female-based. I'm not saying there weren't people who had worked through this right across Europe, but they were just being ignored.

People also hadn't applied it to the British Landscape quite as graphically as you did. That's because I think in farming terms. What is the biggest image in Britain? It is Britain itself. It's alive, it grows our food. Even archaeologists have to eat cornflakes! The miracle of new life springing up from the pregnant womb of the earth...

During

that period in the early 70's when you were researching the book, how

well recognised were the quarter days -

the Celtic festivals? During

that period in the early 70's when you were researching the book, how

well recognised were the quarter days -

the Celtic festivals?

They were hovering in the background, and were being stoked up for various reason as the late sixties wore on. There was a sudden realisation that science and technology were wonderful life -giving things. But the human imagination and human culture cannot be confined within science, and these alternative ways of seeing the world needed an airing.

Were you surprised by how much your book was picked up on, and celebrated by feminists and pagans?The book was hailed as the 'Book of the Year' in The Sunday Times and The Guardian, so that helped stir up interest. And those who came to my house to see me included Dutch people who were deeply into drugs - I had a young family so didn't particularly want my home invaded - and ditto artist Monica Sjoo who got into the habit of dropping into my house, sometimes by herself and sometimes with her followers. I admired her energy, and still do, but I didn't consider myself to be part of her tribe.She had strict views about all sorts of things that I didn't have. One day she came round with some followers, and they sat in my front room while I served them drinks and for several hours they moaned about the horribleness of men, and as they got up one said 'you see - we all agreed on that subject?'. I said 'are you including the person that served you drinks and picked up your glasses?' In other words I didn't exist in their company. I was the wrong sex.

Your work was actually embraced by feminists across world. I think this is why Lucy Lippard picked up on it too. Once when I visited Silbury, I pulled into the car park. It was a lovely sunny evening, and three women came up to me and said 'you can't stop here'. I said 'I can, it's a public car park!'. They said 'no, no, you must go away were going to have a ritual. We are women this is our place'. I said 'OK I'll come back when you've finished'. But had it not been for me they wouldn't have known that it was anything to do with women. I wasn't angry, I just thought well that serves me right! I was glad that they were actively using the place, but I was sorry that there was no room for someone of the wrong gender.

Monica Sjoo was very politically driven, and responded to this aspect of your work. I was working at an oblique angle to what she was doing. It wasn't a one to one fit, but I was pleased to be able to contribute to her difficult task.

Your book helped her link her interest in the Goddess to the landscape in a much fuller way. Most people who are brought up in cities and are only dimly aware that the living land exists. They're not personally involved in its processes, so it comes as a surprise if eventually they focus on that.

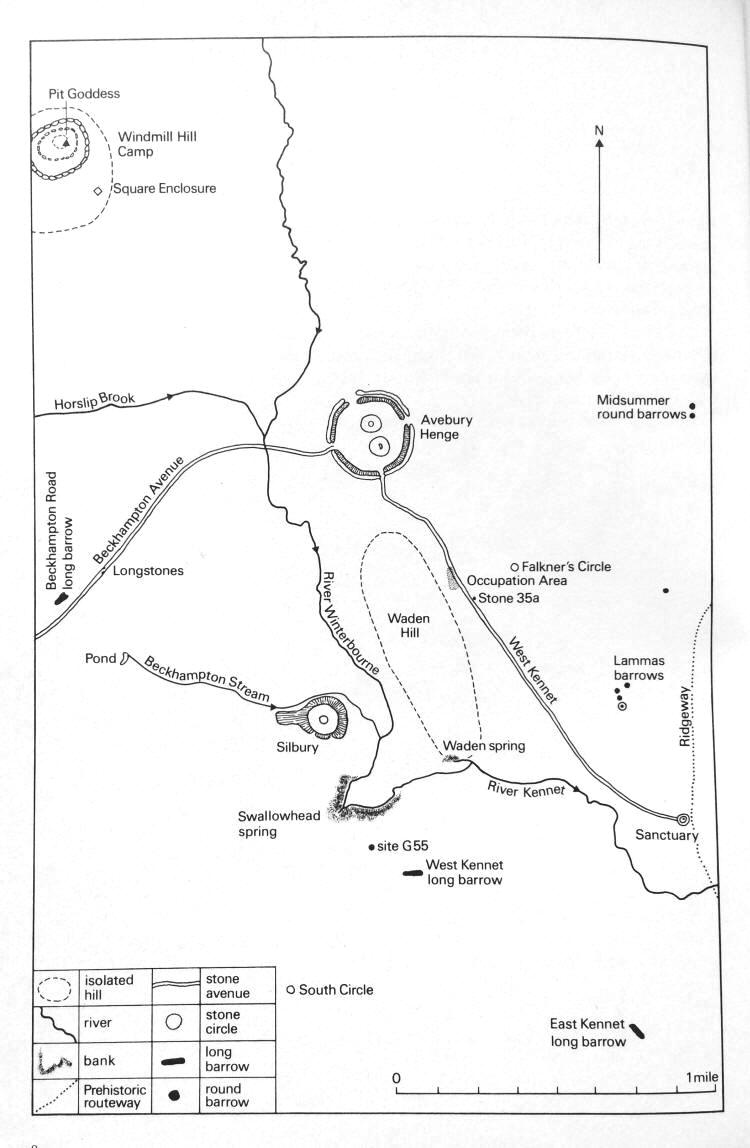

Lots of other people must have got in touch with you. Poet Peter Redgrove, I notice, is acknowledged in your follow up book 'The Avebury Cycle'. He asked me to go down to talk in the art school in Falmouth which I enjoyed for a couple of days. His wife seemed very interested in menstruation, which sounded a bit medical for me, but I know he wrote a lot about that subject. Why he was interested in my work I'm not sure, but 'The Avebury Cycle', which I'd almost completed by the time Silbury came out, was trying to link the year round in a circle, and relate that circle to the monuments around Avebury namely West Kennet Long Barrow and the avenues and so on.

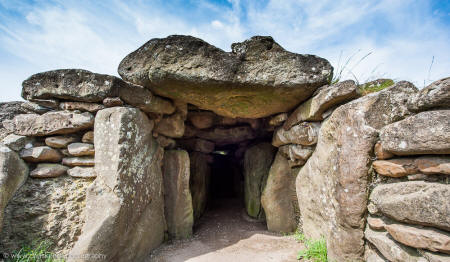

Yes. So in the book West Kennet (below right) was proposed as the site of the Martinmas festival; The Sanctuary, Candlemas; Avebury, Beltane; and Silbury Hill, Lammas or the start of the harvest. What I was saying on one level or most levels was perfectly obvious. Why shouldn't farmers do that? Of course they'd do that. If they're going to have a spiritual dimension to their physical toil, this was it. You could see it on the ground as clear as daylight. But what's clear as daylight to one person is not clear to someone else.

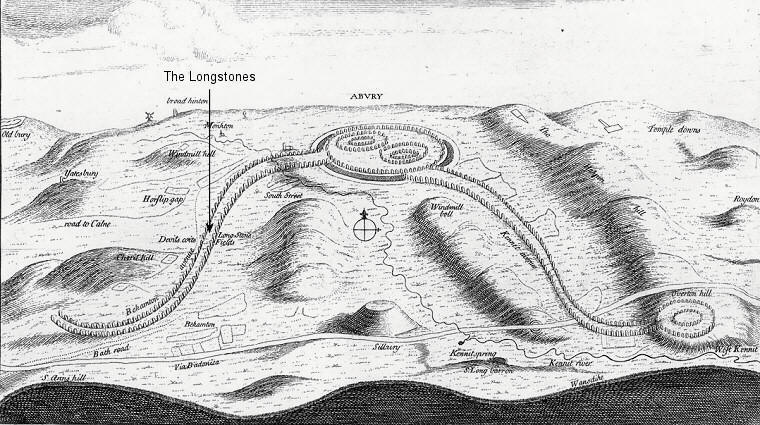

The nearest person who came to it was Stukeley himself, but he was keen to demonstrate that the avenues were Egyptian-type serpents so he wasn't interested in the seasonal round as such. He wasn't thinking in terms of the yearly toil and how it might be visualised.

You describe Avebury as two serpents eating each other... And also male and female avenues. Following the work of many illustrious anthropologists, I was realising that the human species is not isolated in so-called primitive religions, but can actually merge with animal species. So there this medley of animal voices going on within the imagery.

Coming back to people you were in touch with then, I noticed Joseph Campbell, the mythologist was also in the acknowledgements. He was. Before Silbury got anywhere I'd had a couple of rejections including one from Thames and Hudson whose archaeological expert said 'no way'! So I thought I must find a few people who might give my approach their endorsement. I got an A5 sheet of paper and wrote down some addresses, some of them in America, and some of them wrote to say they would support me to get it published, and Joseph Campbell was one of those. And so was Philip Rawson who ran the oriental museum in Durham. I went to see him, and he picked up the phone to Thames and Hudson and said 'you must do this', and they said 'OK'!

Campbell had a lot of cachet in the 60's He was dealing with myth. Storylines that interacted with the ground. Not myth as a separate bundle of thoughts, but 'in and out of the soil' myth.

That's a nice way of putting it...You were subsequently employed as an artist for a while in the late 70's. I was a town artist in Rochdale, working with architects and so on, for the local government. Monica sjoo thought I'd compromised myself and was working for the Establishment! When I'd finished Avebury Cycle Thomas Neurath, head of Thames and Hudson, said 'I'm giving you a car to go anywhere you want in the British Isles'. So I did, and I fell in love with Ireland because all the mythic tracks I was following led as far as Wales, but I could see they were glowing brighter on the other side of the Irish Sea, because they kept their folklore better together than we did.I disappeared into Ireland , and this eventually turned into a book called 'Mythic Ireland' where I hoped to combine the landscape with the movements of the sun and moon, and with the seasons, and with myth, including the visits of Gods and Goddesses to a hilltop called Uisneach right in County Meath.I feel deeply comfortable in Ireland, though I haven't been there for a while.

It sounds broader in scope than your first two books.I was trying to make a multi-stranded bringing together of cultures. I didn't ignore the urban . I thought: 'Dublin exists what can I make of that?' It was a challenge how to bring this into a logical shape that is not too narrow.

One of them was on Taliesin. I'm particularly fond of Taliesin because he was a farm boy. He was accidentally splashed by all the herbs of the year, and is eaten by his mother and thrown into the sea. He turns up on May Eve on the West Coast of Wales, and becomes 'the shining one'. A Sun God. I like the unlikely drama of it. When he is trying to escape from his mother, who is a witch, he turns into different animals, and she turns into an animal that can eat each of those animals in turn, and so he is acquiring an education into the great hierarchy of living things as one unity. There is wisdom in these tales.

'Pagan's Progress' is your most recent work, and in it you describe the importance of the prefix 'Ge' in Geography, which refers to Gaia, or the earth as a living being. We are in such a varied and ingeniously small scale country, that you could stop in any one field and find a story. Having travelled around a lot I wish ed to put some of these mythic happenings into a structure. The mythic structure is important and not a thing of the past.

Thinking again about your impact on Goddess feminists, I noticed Kathy Jones contributed a chapter to 'Pagan's Progress'. I have frequently gone to speak at her annual Goddess Conference in Glastonbury, and actually she has nine pictures by Monica Sjoo in her house. She and I have done guided tours around Avebury together too.

I noticed that you also comment on Richard Long's work 'Silbury Hill (below left)'.

What I've most recently done is an exhibition in Droitwich down the road from here, of Sabrina, Goddess of the River Severn. I tend to swing back and forth between image and word. So the new written work 'Spirits of Severn' I've been working on for a year or so. The great pig Henwen who is the harvest-giver emerges from - probably - the Ballowall barrow near Cape Cornwall, and swims up the Severn estuary, crosses into South Wales and gives birth at a hill called Grey Hill in Monmouthshire. She does that repeatedly. It's a two language river, with a mix of Welsh and English folklore that I want to bring together. I think it's the best thing I've ever written. And I should just mention the most important guide and help in all my attempts, my beloved wife Judy, whom I have known since we first walked together in 1958.

To finish, how importance is the reaction of others to you work? As I mentioned, Lucy Lippard the art critic, was very complimentary about it in 'Overlay' (1981) for example. I never met the lady, but I 'm grateful for positive recognition. Not for personal fame but because I want the story to get out there. The only reason I write at all is because this, I think, is valuable. And the more people that have the chance to focus on it the better. Sometimes it affects people completely. So you just put it on a tray and see who wants to eat it!

Pagan's Progress on Amazon: http://amzn.eu/27qyyZp |

|

|

been

built.

been

built.

And

you wrote two books on Wales

And

you wrote two books on Wales