|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

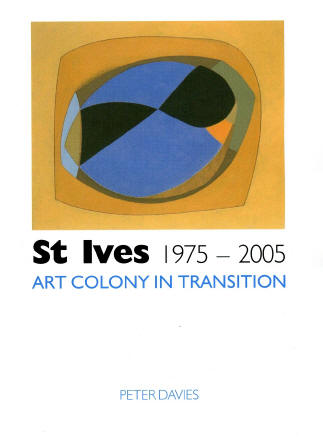

Peter Davies on writing, St Ives, Hilton Kramer and 'The Revenge of the Philistines' Peter Davies (picture below) has written extensively on art from Cornwall in local papers, national papers, magazines and books, and has a reputation as a forthright and outspoken critic. His most recent work, St Ives 1975-2005: Art Colony in Transition' was published in 2007.

Peter, shall we start with some biography?

Can you say a few words about your upbringing and education and how

you found yourself interested in writing and art?

I grew up in South Wales; my father was a

first generation professional - he was a successful lawyer in Newport.

I feel that in my self-styled career as an Art Critic, I'm adopting

some of the lawyer's arguing skills in advocating, promoting or

criticising art and artists. I think I was a bit of an arty type early on, but I didn't take the art school route, because my schooling

was conventional and academic and, although I wasn't top drawer

academically, I nevertheless had enough talent to fulfill my father's

ambition for me that I should be the first member of my family to ever

go to university. I grew up in South Wales; my father was a

first generation professional - he was a successful lawyer in Newport.

I feel that in my self-styled career as an Art Critic, I'm adopting

some of the lawyer's arguing skills in advocating, promoting or

criticising art and artists. I think I was a bit of an arty type early on, but I didn't take the art school route, because my schooling

was conventional and academic and, although I wasn't top drawer

academically, I nevertheless had enough talent to fulfill my father's

ambition for me that I should be the first member of my family to ever

go to university.

I went to a boarding school for six years and was expelled for drugs. I got to university all the same, and studied at the University of East Anglia from 1972-76. My interest in art history stemmed from this time. I was lucky to be in Norwich then because the Sainsbury's Centre was about to be built, although in 1973 we were still in ramshackle wooden prefabs in what was called 'University Village', about half a mile from the main campus. I had the de Stijl expert Jane Becket

as one of my tutors. I was also fortunate in going to Venice for a

term with two dozen others from my year. We messed around a bit and

the tutor went off to Yugoslavia in a huff for the weekend.

Nevertheless, the sight of the Northern Italian Renaissance rubbed off

on us all. I doubt I would have ever taken the difficult decision to

enter the art world as a freelancer without the confidence gained from

these early exposures. Art became both a passion and surrogate

profession, mitigating a

Shortly after graduating I went to Paris with a university mate Terence Maloon. He was on a consignment from ArtScribe Magazine to interview Charles Pollock, Jackson's elder brother. Meeting the brother of a legend was a big turn on for me. We went back to his apartment and saw family heirlooms such as Jackson drawings, which had never been seen by the public. Terence, who was more advanced and knowledgeable than myself, was a bit of a mentor and inspiration for me. He now works at the Sydney Museum of Modern Art. I saw him in London for the first time in 30 years not long ago.

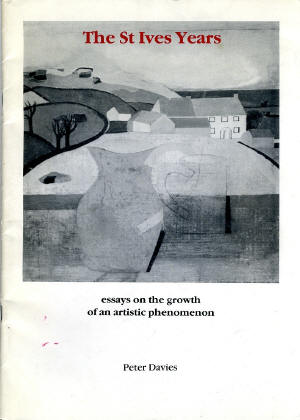

Your first book on Cornish art was

called 'The St Ives Years: Essays on the Growth of an Artistic Phenomenon' (1984).

What led up to this publication? Can you describe this book a

little, and the context in which it was published? Were you

living in Cornwall then? Your first book on Cornish art was

called 'The St Ives Years: Essays on the Growth of an Artistic Phenomenon' (1984).

What led up to this publication? Can you describe this book a

little, and the context in which it was published? Were you

living in Cornwall then?

This was my first stab at writing a book,

although it's more of a pamphlet. It's now worth ten times the

original fiver asking price! It has an archival value, and it covers

what was then untapped art-historical material. Much of this came

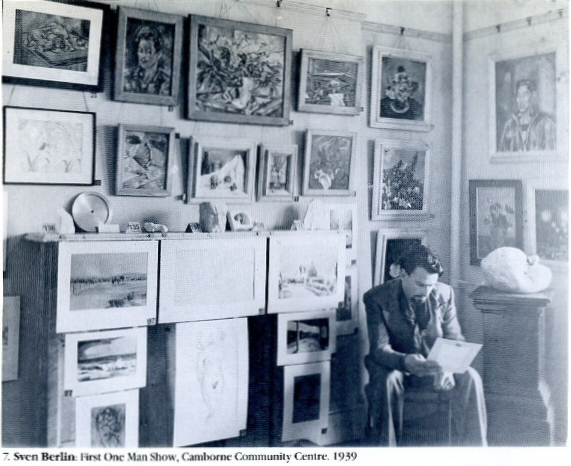

through Sven Berlin (picture below scanned from the book), the Dorset based, former St. Ives legend who I

met in May 1980 at the Poole art centre, where I organised a

six-person show that included his erstwhile post-war colleague Peter

Lanyon.

As a result of that meeting, I did an interview with Sven, which I sold to my friend Peter Townsend, editor of Art Monthly. Peter told me to expand it, and so the interviews included also Denis Mitchell, W. Barns Graham, and Terry Frost. These appeared the following summer and this was my first serious foray into journalism. Sven had a lot of 1940s archive material, including unseen photographs, which I used in the 'St. Ives Years'. To the extent that it predated the boom of Cornish Art, ushered in by the big Tate show in London in 1985, The St. Ives Years belongs to those pioneering studies, such as David Brown's chronology for the New Art Centre (1977), that anticipated the post-1985 great boom. It was published by Bill Hoade, who had a antiquarian book shop in Wimborne, Dorset. Sven also lived in Wimborne, and we put on a Sven show in 1981, for which I wrote the catalogue, and which was opened by the locally based, but far from local, sculptor Elizabeth Frink. I had lived in Poole during the late 1970s, and my art career began there, specifically with a huge mod-Brit show I organised with Jack Lane at the Russell-Cotes Museum in Bournemouth, for which Alan Bowness loaned us five Barbara Hepworths in 1978.

So, you see, my earliest involvement with St. Ives came via Dorset. I've never lived in Cornwall, but have been such a regular visitor that I feel I have lived there. A girl in the local pharmacy said to me "you go away a lot!". I corrected her, to say its the other way round - I come down a lot.

What are your memories of the art scene in St Ives as it was at the time? The art scene in the late 1970s was obviously much quieter, and slightly grieving for the great heyday, but it was the atmosphere of the town and the sense of its art history, rather than the over-subscribed and over-commercialised art scene of today, that attracted one. Also, although fewer in number, the artists there then were generally of a higher quality than those younger ones around now.

Somewhat later In 1994 came St Ives

Re-visited: Innovators and Followers. I remember enjoying this book

when it first came out. What I like about it is that unlike - shall we say

-'conventional' art historical accounts it doesn't suggest that art in

St Ives ended with the death of Barbara Hepworth. Rather it depicts an

active and thriving art colony that is still very much alive and

kicking. Do you want to expand on this? Somewhat later In 1994 came St Ives

Re-visited: Innovators and Followers. I remember enjoying this book

when it first came out. What I like about it is that unlike - shall we say

-'conventional' art historical accounts it doesn't suggest that art in

St Ives ended with the death of Barbara Hepworth. Rather it depicts an

active and thriving art colony that is still very much alive and

kicking. Do you want to expand on this?

In between the 1984 and 1994 St. Ives books

I wrote a book "Art In Poole And Dorset" (1987), which obviously

reflected what I've explained above, i.e. my early Dorset start in

art. Then during the late 80s and early 90s I wrote "A Northern

School" (1989) and "Liverpool Seen" (1992), so I earnt my northern

spurs with those. "A Northern School" together with "After Trewyn" and

my recent "Art Colony In Transition" are my best books.

Writing the northern books made me realise that there are intimate connections between St. Ives and the equivalent art scenes in the north. Many northern artists have gone down to St. Ives, and I wrote a chapter in "St. Ives Revisited" called "Northern Migrants". Hepworth herself was of course northern, although from Yorkshire, and 'A Northern School' was dealing with Lancashire. In art, one book or project spawns and leads to another, and the sense of an on going art colony that you say you detected in "St. Ives Revisited" eventually led to "Art Colony In Transition". "St. Ives Revisited" took a year to write and covers a lot of ground.

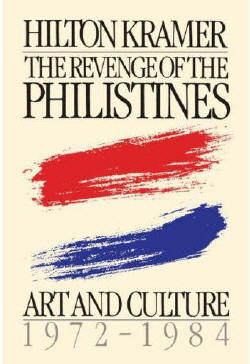

One of its selling points is that Hilton

Kramer, former New York Times art critic, wrote the foreword. This was

a real feather in my cap, because he is one of the leading American

critics. I got the Kramer connection through the London gallerist

Bernard Jacobson. I think the hidden agenda for Kramer helping me out

was

Having said that, Tony Caro was a very good and supportive friend to me at an early stage of my career, and that is something I will never forget, and when all is said and done they are both very good, if not supreme, artists. "St. Ives Revisited" was a bit rushed and, looking back, the text is a bit lumpy in places - I write more smoothly these days! But, again, there was some important material in it.

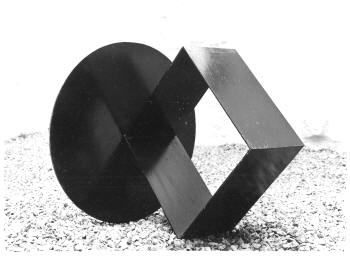

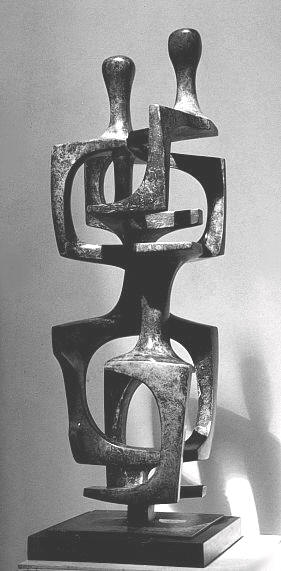

After Trewyn: St Ives sculptors

since Hepworth was next to be published - in 2001. Sculptors like John

Milne, Brian Wall (picture above right) and Paul Mount (picture

below), though mentioned in passing in eg

Tom Cross' 'Painting the Warmth of the Sun', had been a rather

neglected group up to the time of the publication of the book. What is

your evaluation of their work now? How do they fit into the bigger

story?

This book is, as I have said, one of my

best. It is a really tight and coherent study of a neglected enclave

of the post-war St. Ives modern movement. It was a real joy to write,

not least because I was particularly friendly with almost all the

participants. I find sculptors in general a bit easier than painters -

they are less prone to ego problems - and the cost and challenges of

heavy materials and heavy labour keeps their feet on the ground.

John Milne was the only one I didn't know - he died prematurely in 1978 just as I was getting involved in St. Ives. Having written a monograph on Milne for the Belgrave gallery the year before 'After Trewyn', I simply re-used my text for Belgrave for After Trewyn. Also Brian Wall (picture top) in California got a commission for me from an American university. That went wrong, but I was able to simply divert my text from the still born American project to 'After Trewyn'. I went to stay with Wall a couple of times in the south of France, and Maggie and I went to his New York opening in early 1998. Rodger Leigh (picture above left top) was a friend who I used to stay with in Wiltshire, and 'After Trewyn' offered me the opportunity to give him his just desserts. Tom Cross is a diligent researcher but an an extremely mediocre writer - his writing is sycophantic towards the big names and the establishment that he clearly sees himself as a part of. It also lacks critical depth and independence of judgment and his exclusive books, with their politics of exclusion, are absolutely anathema, as indeed they are to many people. However, unlike many people, I think he is a reasonable painter, and I wish he would keep to that, rather than being a pompous spokesman for what he sees.

'St Ives 1975-2005: Art Colony in

Transition' is a lovely looking book that came out last year, published

by St Ives Publishing. It was criticised a little on this site, partly

on the forum and partly in a separate article.

We need to get this straight. My successful

new book was not primarily a book about St. Ives art now; three

quarters of it was about St. Ives in the 70s, 80s and 90s. Now the

1970s is already art history, enough time has elapsed for us to look

objectively and impassively.

There may well be a pluralism in St. Ives now, but I still think that the coherent colony you refer to is intact in terms of a younger generation who, consciously or not, develop the styles of their post-war predecessors. Take the following as examples: Antony Frost following his father, Henrietta Dubrey drawing on Lanyon, Hilton etc., Jason Lilley using Nicholson's and the unrated David Haughton's architectural skyline, Patrick Haughton and Morag Ballard (below left and on the cover) following John Wells, Clive Williams and Larr Can influenced by their teacher Alex McKenzie, Linda Weir working in the tradition of fellow Mancunians Alan Lowdnes and Fred Yates. The list goes on and on. If this is not evidence of a coherent colony, or school, on going and flourishing, then my name is Alistair Campbell. Regards the quip that there was little recognition of new art, or multi-media post-modern art, I would argue that this is a parasitic and odious development that does not belong either to St. Ives or the west-country scene in general. The said developments are decadent,

dumbed down, a symptom of deregulated neo-liberal Britain and America.

Deregulate the economy, and you deregulate social principals, morals

and ethics and aesthetic standards. Julian Spalding, formerly head of

Sheffield, Manchester and Glasgow art galleries, wrote a compelling

book called "The Eclipse of Art" (Prestel, 2003) which goes

into all this. Julian wrote to me from Edinburgh congratulating me on

my attack on Tate St. Ives' dreadful exhibition "Real Life" calling my

article

Julian, however, also warned me that those in positions of power would be deaf to my views, and he himself found himself outlawed for daring to suggest that the art establishment had gone wrong. Timothy Clifford, the outgoing supremo of the entire museums of Scotland, told me that Julian wouldn't get another major museum job as a result of his outspokenness. He's a hero in my book. Sven Berlin once said to me, when I was a rookie art writer, that whatever it costs me, I should keep true to my beliefs, and I'm proud to have, more or less, done that.

'Real Life' was the video art show of 2002 wasnt it? It included work by eg Sam Taylor-Wood and Mark Wallinger (below) Yes. Some of the early conceptualists were original and important artists, Eva Hesse for example. But what we have now is an anti-art bandwagon, a celebrity culture freak show, that bypasses any grasp of the language of fine art. I'll have nothing to do with it. Like surrealism, the legacy of conceptual art is often best when it is integrated into traditional fine art practice, i.e. painting and sculpture. I particularly like a conceptual approach to subject matter in more recent trends of figurative painting or American photo realism or New Image Painting. I'm interested in photography as an art form and own a Lee Miller war time snap. But installation, video and performance are not fine art - they are rather third rate theatre or film, and therefore should confine themselves to populist entertainment centres, rather than high-jack serious art galleries, like Tate St. Ives.

Not only Anthony Caro, but my friend the late Michael Kenny (below right) placed their sculpture beyond the plinth, using the floor, wall or even ceiling of the surrounding architectural environment as part of the overall context of the sculpture. Kenny, I wrote a book on in 1997, and in it I emphasised the important relationship between the illusionism of drawing or the painted mark, and concrete free-standing full-in-the-round. As I’ve argued earlier the use of conceptualism or, in this case the environmental aspect, added to the successful outcome of Caro’s or Kenny’s sculpture. Paul Mount in St. Just also places his sculpture in relation to architecture. The two fields clearly overlap. The problem with installation work per se, however, is there’s often no syntax, no plastic discipline and no tight or vital tension within the work. It depends more on sociological interpretation, and so falls down as a formal statement. You mention artist films: do you mean Andy Warhol’s films? I think Warhol’s films are really good: they have a freshness, originality & possibly humour. The problem is the bandwagon that follows taking the original statement out of context and usually debasing it. To deny performance and film as an art form does not, as you suggest, undermine my position as a critic. On the contrary, it strengthens it and I take quips about my being a reactionary as a compliment. Performance is just that – a pseudo-avant garde branch of the performing – as opposed to plastic – arts.

Is it wrong that art should be subjected to a sociological interpretation? You also say that multi-media post-modern artworks are 'decadent; dumbed down; a symptom of deregulated neo-liberal Britain and America'. What many like about St Ives modernism is the fact that it reminds us of another era: an era before post-modernism, before the consumer boom, before the class-less society, before feminism, before colour TVs, computer games and Amazon.com. But if multimedia art is a reflection of now, surely that’s a good thing? Or are you suggesting that it is better to cling to the past, to the old hierarchies, as a way of denying the present? No, I am not suggesting that it is better to cling to the past, to the old hierarchies, as a way denying the present. What I am suggesting, however, is that the achievements of the St. Ives school - shall we say between 1939 and 1995 - are timeless. The expression of the modern movement was not wasted on the incidentals and superficial distraction of 'modern life' during that time - though obviously such things peripherally infringed on the work. Rather, the great art spoke of, and reflected on, the human condition, the rebuilding of a war-ravaged world, the meaning of life and of existentialism etc.

You're therefore also saying especially in relation to video/performance and installation, that the art establishment (eg Tate) has got it wrong. That is a daring position to take and if nothing else I congratulate you on your boldness. You also imply that modernist art as it was in the 40s, 50s and 60s was OK, but then at some point it all went wrong. In art history terms when was this in your view? Would an artist like Andy Warhol symbolise the moment when things changed: his interest in celebrity, his films, his interest in 'mass culture'? Or was it perhaps the conceptual artists, and Fluxus artists before them who were not interested in aesthetic or beautiful objects that could be bought and sold? Like Hilton Kramer and Julian Spalding quoted above I think it all went wrong during that malaise peculiar to the later 1970s, when late modernist movements like Abstract Expressionism, Pop and Minimalism ran their courses. I’d personally also link the problem to Thatcher and Regan when monetarism and all-out commercialism took hold at the expense of social, cultural and aesthetic value. As regards Fluxus, it was an intellectually interesting movement with probing philosophical meaning, which is not to say that I necessarily liked the end product. I have mixed feelings, for example, about Yoko Ono, not least because I am, if you couldn’t guess, a Beatles fan in general and a John Lennon fan in particular.

Art did become extremely pluralised in the late 70's. Picking up on another comment but moving the discussion on: describing eg video art as 'a parasitic and odious development that does not belong either to St. Ives or the west-country scene in general' seems to suggest that art from St Ives or Cornwall should be different from that elsewhere. This plea for 'localism', if that's what it is, is appealing and one to which I am sympathetic. Actually I’m not suggesting art from St. Ives and the West Country should be different from elsewhere. Rather I’m suggesting that the glorious 50-year old fine art tradition in the West Country (which, arguably, is centred on St. Ives) is an entity with is own distinctions and characteristics. Obviously, there has been osmosis between Cornish art and that of the equivalent art at Corsham, Bristol, Liverpool, Newcastle and London. And, of course, the St. Ives middle generation corresponded with the New York school, so we have transatlantic couplings like Wynter and Tobey, Lanyon and de Kooning, Heron and Francis or Louis, Frost and Gottlieb or Motherwell etc. But the anti-art instincts of post-modernism run against the achievements of great mid-century art. It is why Hilton Kramer wrote his book “The Revenge of the Philistines”, a copy of which this eminent writer gave to and signed for me.

links to Peter Davies books on

Amazon:

St Ives 1975 - 2005: Art Colony in Transition

|

|

|

tendency

to be a drop-out and wanting to do my own thing and on my own terms.

tendency

to be a drop-out and wanting to do my own thing and on my own terms.

St. Ives is not really a sculpture

movement - Barbara Hepworth and the After Trewyn sculptors not

withstanding. It is primarily a colony of potters and painters. All

the 'After Trewyn' sculptors are fine artists and craftsmen. They all

developed the rather obvious influence of Hepworth to create an

individual style that, in terms of a soft sensuous constructivism, can

be considered quintessentially St. Ives school.

St. Ives is not really a sculpture

movement - Barbara Hepworth and the After Trewyn sculptors not

withstanding. It is primarily a colony of potters and painters. All

the 'After Trewyn' sculptors are fine artists and craftsmen. They all

developed the rather obvious influence of Hepworth to create an

individual style that, in terms of a soft sensuous constructivism, can

be considered quintessentially St. Ives school.