|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Ralph McTell on The Folk Cottage, The Isle of Wight festival and COB Phone interview by Rupert White.

Many of the early 60's folk guitarists in Soho, like Wizz

Jones, were described as beatniks. How did 'beatnik culture'

affect you as a teenager?

Very much. I had a bit of a troubled childhood. And like many boys who come from broken homes I had a dodgy early teenage period until I discovered music. I properly discovered roots in American music when I was about 16. I fell in with the beatnik crowd in Croydon where I lived. The four beatniks I knew were all a couple of years older than me. There was nowhere to go, so some of these fellers got themselves a little flat and I spent hours round there listen-ing to Art Blakey and Miles Davis and people like that, and beginning to be interested in alternative beatnik cultures revealing all the 'mysteries of life' that I too wanted to find out about after abandoning religion and conventional ways of going about things. I'd been in the army as a boy soldier, and I was at art college where I met some lovely like-minded people. But music and the self-imposed discipline of learning to play by listening to records more than having any teachers - there was noone to show you what I wanted to learn - the network, even without phones, led us to each other. I acquired some degree of skill and Wizz noticed me. Wizz was only about 5 years older than me and had been down in Cornwall in the late 50's.

Wizz has mentioned Malcolm Price to me as, probably,

the first of the Soho guitarists to come to Cornwall...

Malcolm lived in a game-keepers cottage which was a squat and which had some amazing characters including David Hockney (?) and dropouts from the late 40's who had been living in the deserted cottages in the woods. Malcolm was one of the finest flat picking guitar players I'd ever heard. He was funny and witty, when I saw him in folk clubs later. He was there with his runaway teenage girlfriend encamped in the woods at the bottom of the Heligan estate.

How influential was Jack Kerouac back then?

I never read 'On the Road' but absorbed enough about it. But my mentor by this time was Woody Guthrie who'd done the travelling for socialist reasons. He was a committed union man, so it was a combination of a political view, music, poetry and guitar playing. Woody's message better served my purposes rather than Jack's which was more modern jazz, though I took that on board as well. I still love jazz. I'm one of the few folkies who can genuinely say that.

I had lived in a squat in Poole in 1961/62 and I listened to all

that music when I was struggling with my guitar playing. Beat

culture was education out of school. You had to ponder the

poems, and the stories, and the flow-of- consciousness stuff.

And Dylan was a student of all that, so when we heard Dylan we

got him too.

It was going on in other cities: Liverpool, Glasgow and probably Dublin. When Wizz came to Cornwall he was taken to court for stealing a tuppenny bar of soap out of the gents toilets in Newquay. That's how reactionary people were. And liquorice papers around cigarettes: they all thought I was smoking dope in The Folk Cottage! The whole culture gave us an identity, and a discipline, and a more enquiring mind.

Did it also inspire you to travel??

My Dad was in the Desert Rats and had been abroad during the war, but none of the rest of my family had even thought of travelling. We hitchhiked everywhere because it was 'noble'. You took the rough with the smooth. Boys had to wait for hours, girls could go anywhere in comparative safety. I hit the road when I was 17 and was still travelling when Wizz invited me to come and play with him in Cornwall.

People don't hitchhike in the same way now...

Hitchhiking wasn't frowned upon. You were taking a chance. You

didn't know if you would get there, and who you would

meet. We'd say things like 'I'll see you in Trieste' and it

would take as long as it took to get there. I got as far as

Istanbul and would have gone further but I got ill.

I didn't even know where I was going. I bought a map that cost

sixpence and by the time I got to the South of France it was in

about eight pieces: 'No money in my pocket, a cigarette in my

mouth no fixed destination but some vague direction South'. I

had no wish to sit on the beach. I wanted to keep rolling on and

playing my guitar; earning money by busking. I had a ten

shilling note when I left England and a ten shilling note when I

came back.

Wizz and I played in the Mermaid in Porth (in 1966) until we

were banned because too many people came. It was a residency

that lasted a few weeks. We didn't have a microphone and at

first it was extraordinary. People kept pouring in. We were paid

three pounds a night. Wizz insisted on splitting it 50:50 but I

said 'no - I'm on my own you've got two kids you have two

pounds, I'll have one pound'.

It was the start of a wonderful adventure. He'd heard there was

a folk club (The Folk Cottage - picture above) up at a barn in

Mitchell and it was like an old-fashioned sing-a-long. All the

artists sat on the stage: Brenda Wootton, John The Fish, John

Sleep and John Hayday, and they sang songs one after the other.

I found a caravan at the back of the Edgecombe Hotel which had

been standing there for years, and we made an offer to the bloke

who owned it. He said I could take it away. One sunny day John

Hayday towed it to Mitchell where it was illegally parked in a

field. It leaked. It had a roof made of hardboard and canvas. It

had no brakes, it fell off the trailer once and went flying down

the road. There was no traffic in Cornwall in those days and we

were able to pull it out of the ditch and drive it on.

What sort of things did you play at the Folk Cottage

initially?

Almost exclusively American stuff, based on how interesting it was to play on the guitar. My preferred style was finger-style guitar playing which is more intricate than flat-picking. It was songs by Patrick Sky, Tom Paxman, Bob Dylan and some old blues things. But I was also playing a couple of Bert Jansch songs. He was always one of my guitar heroes but at that stage we hadn't yet become close friends.

What about original songs?

I'd just begun writing my own songs. One of the regular

musicians, John Sleep, had a friend called David Dearlove. David

wrote songs, and had been working for Southern Music, I think as

a publisher and he dropped out of the rat-race and moved to

Cornwall to become a postman. He found The Folk Cottage and

began to contribute songs to the repertoire of John Sleep and

John Hayday. One day he asked if one of the songs I was playing

was my own. I had started writing it in Paris before I'd come to

Cornwall. He said 'its rather good you should send it to

someone'. I sent a bunch of songs to Essex music which is where

David recommended. They were dismissive really but they said

'keep us in the loop'. Then I wrote 'March of the Emmetts' which

happened to be recorded. The audience responded really well and

there was a lot of laughter on the recording, and it

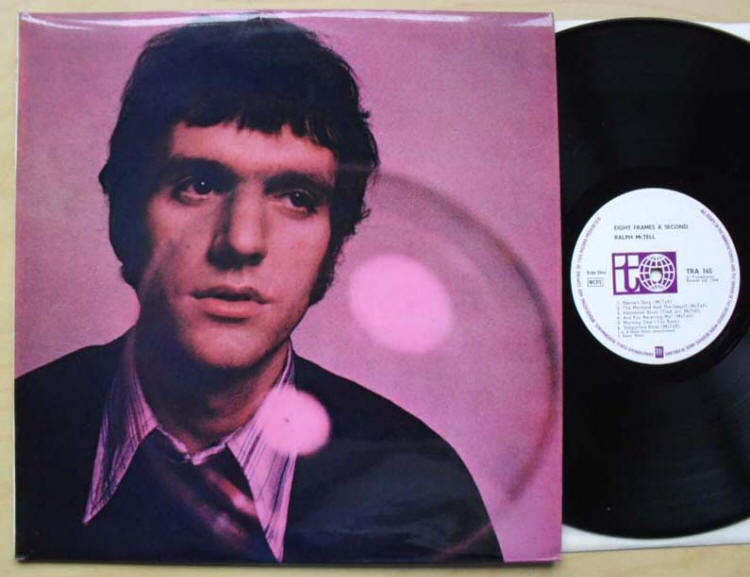

was laughter I think that helped me get the contract with

Transatlantic Records a year or two later.

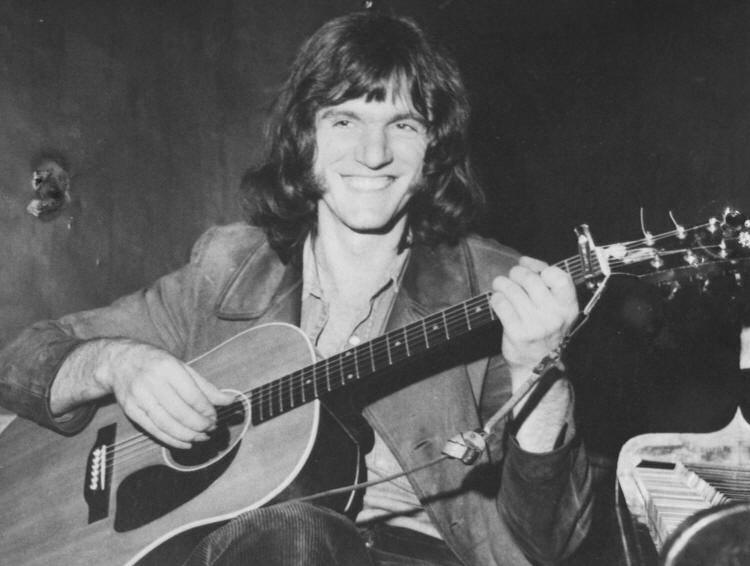

At around this time I formed a jug band (picture top) because I

couldn't find anyone good enough to play proper instruments. But

my friend Henry Bartlett, who introduced me to tons of

music, played the jug and another guy who was

a kitchen assistant in one of the pubs in Newquay - who was a

great character - called Micky Bennett. I gave him a washboard

and tried to teach him to play, but frankly he was the worst

washboard player in the world! But the effect was so funny on

stage. We've got loads of tapes of people just roaring with

laughter at the antics. It was fantastic. That was 67 - just.

Talking about your early

songs, there are a few that were

inspired by Cornwall..

'The Mermaid and Seagull' was the most famous one. It was requested all the time. It's a whimsical fantasy about getting bored. It's a song about people sitting about talking rubbish in a pub, and me going out and wandering off on my own and imagining that I can hear the mermaids and brass bands and all those Cornish things as I strolled along the beach. It was so popular, and so it appeared on the first album, together with a bunch of songs which David had heard me play.

In 1967 I had a little boy called Sam but it (the caravan and

Folk Cottage farm) was entirely unsuitable for him. That summer

was idyllic. It was the summer of Sergeant Pepper album, the

revolution had taken hold and the music was incredible. I was

about to make my first album. There was a sense of change in the

air and a true feeling that music was helping to change the

world. I first heard Sergeant Pepper on a portable stereo

gramophone up under the cliffs in Newquay. Somebody had bought

the album and we were sat there listening to it with our mouths

open.

With a baby son now it was clear I had to do something else. There were no flush toilets at the farm. There was a milking shed a portable Elsan and one cold water tap. We were placed on an emergency housing list, and we moved back to Croydon where I got a council flat with my wife and son, and I applied to start teacher training. Though I didn't have enough qualifications I had some 'history', and they had a policy that if you were an interesting person you could add something to the college culture by being a bit different.

I had good intentions, though I was slightly depressed about it

having had so many years of freedom, but suddenly I found that I

was getting gigs and I was trying to do the two things.

Travelling round the country and then getting back in the early

morning and going on to college, I was falling asleep in class.

At the end of the first year I said to my wife: 'what do you

think?' and she said 'well you've got to do music'.

Can you say a

bit

more

about

the music industry then, and some of the other influential

people that were around?

Jimi Hendrix was exceptional. Jimi, in any generation, would have been a genius. Some people have it - like Charlie Parker and Art Tatum. Lots of black musicians seem to have this gift of music that is disproportionate to the way their lives have been. Its the highest form of music to me. Jimi was beyond reach for most of us. We're artisans, we work hard, we sweat, we learn to play to a degree of proficiency but he could play it without even tuning it up, just compensating with his fingers.

What about The Incredible

String Band (ISB)?

They were the other side of it. They had an incredible influence on us down here because their instruments were very organic, and the roots were fascinating: a mix of American, North African and British plus a heavy LSD vision. They were expanding your thoughts and playing instruments that weren't always in tune, and the harmonies were approximate but there was a spirit there which we found totally elevating.

Mates would come round to the caravan and listen to John Peel's

'Perfumed Garden'. We enjoyed the music. I was one of the

few who thought that John Peel didn't always get it right, but

he certainly got it right as far as the ISB were concerned and

we found it all very inspirational. By that time Clive Palmer,

the founding member of the String Band had moved to the same

field as me in Mitchell, virtually.

He took over Willoughby's caravan. Willoughby (the farm-owner) had two years of brucellosis and he was as ill as can be. He managed to keep his 6 cows together, but finally he got beaten and he rented the caravan to Clive, Mick Bennett and John Bidwell, who together formed the band COB.

And you engineered their first album

They were n't a great band - but the albums were great. I'm very

proud of what we achieved there.

Meanwhile your own career

started to take off, and you managed to fill some big venues

There'd been this groundswell. I was there at the right time. Largely word of mouth, but don't forget there was this network of clubs. John Renbourne introduced me to a Northern promoter called Wim White and after the first appearance at his club I got six more gigs. I looked at an old diary the other day. I was working 7 nights a week, and travelling in my little GPO van with a ladder-rack on the roof. I was driving all over the country for six quid a night.

And

in 1970, you were put on

the main stage at the famous Isle of Wight festival. What do you remember of that day?

The speakers and PA were not that loud - nothing like they have now.

The DJ, Jeff Dexter, was sitting on the top of the stage playing

records between the acts and I got an encore and I was waiting

to be sent back on. My manager was out the front and I thought:

'do I go back? what do I do?'. I was waiting for someone to tell

me. Then Jeff put on a record, so my manager rushed out onto the

stage in front of 500,000 people and grabbed him by the beard,

and nearly pulled him out of his chair! It was extraordinary. I

didn't even have a pick-up on my guitar, and I had my lucky

shirt on which was a red tennis shirt which I had swapped for a

set of strings in Milan.

I was ever so glad I did it, but my only regret was that I

didn't get to see Jimi Hendrix at the end of the evening because

my manager had sensed that panic was setting in, and the crowd

was getting more and more restless. I had to wait a very long

time to see how intense people felt about the music. It was the

end of something.

I saw everyone who played the same day as me. I saw Pentangle,

Donovan, Moody Blues, watching from the side of the stage. My

manager insisted on catching the last ferry back. Bert Jansch

was asleep under the stage. I knew Jackie McShee, because she

was a Croydon girl, and I used to sing with her sister. She

watched show. I knew Danny and John Renbourne by that time. John

helped me in the early days. He told people about me.

Can you say a bit more about Clive Palmer and COB, and your involvement with them?

I think I first met Clive before Cornwall. I have a feeling

that, after Wizz and Pete Stanley split up, Clive and Wizz

formed a duo and played on 'Country meets Folk', and there are a

couple of tracks from the BBC. I met him in London. Wizz and

Clive were doing gigs as a duo at the Folk Cottage and they were

fantastic - they really were.

I got to know him better during '67 when living in the field.

John Sleep was a teacher at Newquay Grammar School and he

encouraged some of his pupils to get up on stage at the Folk

Cottage. Tim Wellard and John Bidwell were a duo and

they played on stage at the Folk Cottage before I left. So I

knew John as a really hard-working young guitar player, who was

determined to get on, and he became quite accomplished and he

fell under the spell of Clive, and moved in with Mick.

Mick was a bit of a Jack-the-lad character but blessed with this extraordinarily powerful voice for the skinny little whippet that he was! He was influenced by all the music around him. He started writing poems and I like to think that I helped him regarding the basic rules of scansion and stuff like that, and he started reading avidly and, with Clive - let's be frank about this - there were drugs taken. Clive found a soul brothers in Mick and John, and they experimented with time signatures, and they bounced off each other very effectively. Clive has this beautiful simple, almost shaman-like approach to music and art and he's drifted along, carried by music all his life. And there they were, trapped together, living on potatoes through the winter of 67/68 and not much else - dope and hope - and they wrote these songs. And they were strange and rather beautiful.

I got my manager of the time, Jo Lustig, to listen to them and

he knew that Clive was important because of the ISB and he

negotiated a deal with CBS with three acts. One was COB, which I

then produced.

I must be honest they were so undisciplined - it was a

nightmare. Several people told me I was completely mad to do it,

but I did have faith in the boys and I'm very proud of what I

achieved and the records sold in their thousands all over the

world - for which none of us received a penny.

COB's music is unusual, and very otherworldly

All three of the members were otherworldly! I particularly liked John's inventiveness. He made an instrument called a dulcitar which is a cross between a dulcimer and a sitar, so you had a sitar effect without having to spend 20 years learning to play it. So you've got this mystical eastern sound to it: strange harmonies, lots of minor keys, and a biblical influence. Mick is Jewish and he decided he wanted to understand more of the Bible and he wrote these lovely warbling psalm-like songs and Clive put tunes to them and I helped with a couple as well. This mixture of styles I found terribly attractive. I didn't ever expect it to be hugely successful.

The titles of the albums we made up. The Tartan Lancer was the

name of the off license at the bottom of my road in Putney. And

Mick's jokey Jewish title Moyshe McStiff was a combination of

Scots tradition which Clive had immersed himself in and a Jewish

name, and I threw in the sacred heart to confuse it even

further. Some American critics have written pages on the meaning

of the title alone! Mick and I still laugh about this now -

and one reviewer even read the whole bible before he wrote his

first review.

It was recorded very intensely over a few days. I had to wing it

and trust my intuition. I managed to rescue 'Solomon's Song' on

the second album by getting Danny Thompson (of Pentangle) to

play on it. He had brought his young boy around to see the

recording studio, and I said 'You haven't got your double bass

in the car have you?' 'Yes why?' 'This song is a nightmare its

got two movements in it and we can't get them to stick

together'. Danny roared all over it and helped knit it together,

that's how that track came together.

On 'Eleven Willows' which is an instrumental I got Genevieve, who was playing percussion rather badly, to sing quietly but she was not at all confident so we had to tweak the vocals, and Bert Jansch recorded it years later.

This is one of a number of interviews carried out early in 2012, as part of the research for 'Folk in Cornwall': Antenna Publications (2013). https://www.amazon.co.uk/Folk-Cornwall-Musicians-Sixties-Revival/dp/0993216404/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1514571944&sr=8-1&keywords=folk+in+cornwall

|

|

|