|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Sovay Berriman on Cornwall, Cornish identity, Eek! and Meskla

Interview Rupert White

Let's start by talking about the group show 'Eek!', and about your circumstances at the time. Had you just moved back down? I finished my MA at the Royal College of Art in London and moved back to Cornwall in 2003. I was just really clear that I wanted to maintain the level of making that I'd had, but in Cornwall, and I also wanted to connect to other artists in Cornwall because I'd been away for a number of years, and wasn't embedded in the art scene in Cornwall at all. So I happened to meet - through teaching at Cornwall College -Jacqui Knight who'd also returned the same year as me from the Slade, having done her MA. Also a local girl, we just got on and we hatched this idea to have an exhibition that brought some of our peers down from London to show, but we also did an open call out for artists in Cornwall to take part in the exhibition, so that we could set up a load of connections and dialogue. But also for ourselves, we could begin to see ourselves in this crossing moment, in these two places at the same time.

'Pass' by Sovay Berriman at Eek!

And ironically, of course, Eek! was just across the way in what is now Krowji, but before then it was just called the Old Grammar School, and though there were some artists already using it, it was quite tatty and hadn't been developed. When we started planning the exhibition, there was nothing here, just broken glass and leftover geography books! Then, throughout that year, the building started to be populated with artists. And I was still using the studios at Treruffe that Christine Spencer-Green setup. Siobhan Purdy was there as well, and a number of other artists. When Krowji was set up, Ross Williams spent a lot of time speaking with us down at Treruffe to make sure that Krowji didn't undermine Treruffe and could encourage and support the studios that were already in existence. In fact they shut down due to developers eventually, but yeah, Krowji was a really supportive endeavour.

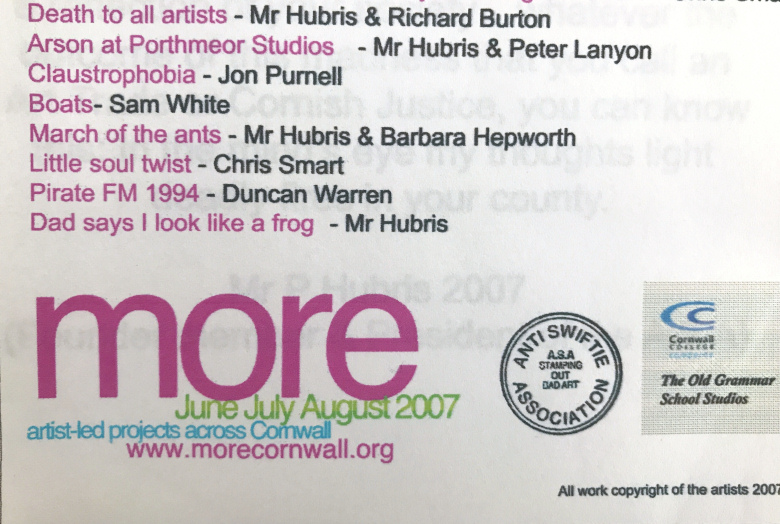

After Eek! You were involved in various other projects. MORE Cornwall, I remember, and also Santa's Secret £10 Tombola. MORE was a sort of umbrella project that helped to connect and advertise various artist-led projects during the 2007 Social Systems pan-Cornwall exhibition organised by Project Base. Also there was the launch of the new Exchange gallery in Penzance. Project Base grew out of St Ives International. So there's been quite a legacy of those kinds of cross-Cornwall multi-site projects, and MORE Cornwall was an independent version of that.

Shortly after, you went off to Bristol. When was that? 2008. I was offered the opportunity to be artist in residence at Spike Associates programme at Spike Island. That was for the year of 2008. So I took it. I was feeling quite frustrated about opportunities. And it seemed a really good opportunity and it worked for me personally.

Daryl Waller's Anti Swiftie Association CD as part of morecornwall

You settled in Bristol for a few years didn't you? I was there about four years. It was really good not to be living in London or Cornwall, but somewhere else that opened up the rest of the country. I ended up meeting a load of artists based in Swansea and Cardiff and Newport, and also in Manchester and Birmingham. Then I went back to London for a bit. My mum moved to London in the very early 80s, so I spent a lot of my childhood in London. I was approaching 40, and I didn't have children and wasn't in a relationship. People around me were having children and settling down into a sort of traditional family situation, and I just didn't fit that scenario. I was there for four years, met some new people, and did this project 'Molluscs Hunt Wizards' in 2014, which took me walking through the deserts of Mongolia and parts of Australia. And it was through that project that I felt, it's sort of sentimental, but I felt like I needed to be home, where love is for me, with my nieces. And there was just something about coming home, and also wanting to develop a skill that was a fundamentally useful survival skill. So I came back to Cornwall and trained as a plumber.

And what year would that have been roughly? That was 2015.

So you've yo-yoed between Cornwall and other more urban places. I think that's quite common. People feel the need to move away, but then they come back again. There can be an ambivalence about being in Cornwall. Yes. But also if there's no ambivalence, even if Cornwall really matters to you, as it always really mattered to me. I've always felt really powerfully connected to being Cornish, and to the land of Cornwall. For me going away was, strategically and politically, about wanting to gain experience. And wanting to challenge myself, challenge my edges, sort of knock myself about a bit in a different way. And I do think in Cornwall we self-sentimentalise, and don't recognise power, innovation or ambition on our doorstep, and we don't recognise or value the experiences that people gain just through living and working and being in Cornwall. We only trust it if it comes from outside.

So, in other words, you don't have to travel to produce good art. No. There's so many artists, that just produce fantastic work and they've been solidly living in Cornwall for decades, like Delpha Hudson for instance.

Which brings us to Meskla. Eek! was very much about visual art, and had a conventional exhibition format. Meskla is much broader and more diffuse, and it's difficult to pin down exactly what it is, but that's obviously what you intended. Why did you broaden out in this way? That's partly to do with my maturing like as a person and as an artist. There were times where I was deliberately thinking, OK to be an artist I need to be making like objects and things. However, the sculptures and things that I made were often assemblages that could be taken apart and put back together. So I think that that 'expanded' way of thinking is fundamental to the way I approach art-making. And now maybe, through confidence, maybe through a like, 'ah what the hell' attitude I'm happier to present that on a larger scale. It's really important that this is multi-platform artwork so it can reach all the different audiences it hopes to reach, and include the different voices it hopes to include. It's something that is durational, as well as tangible and physical. And something that has lots of space for all the different potentials of what Cornish cultural experience is. I was mindful of its legacy, and not just allowing that conversation to disappear. That's why I've made these solid cast-copper pocket sculptures (above) that are given to people who contribute rubbish sculptures to the exhibition, so that there is some token of the permanence of Cornish cultural identity and the permanence of the conversation around that.

The Meskla podcasts are amazing. Can you talk a bit more about them? The thing that ties them together is this exploration of Cornish identity, but of course they go in lots of different directions, don't they? I wanted to connect the conversations, that are very locally focused, through the rubbish-sculpture making workshops, to a broader global discussion, that is sort of multi-directional: historical as well as geographical. It felt like quite natural to reach out to people who had experience or research around some of these points of interest. So the podcast is basically me doing research, just recording our conversations, essentially, and opening them up so that they're public. If we put a conversation around indigenous languages and the Cornish language next to, I don't know, a conversation about Hedluv and Passman or ceilidh calling or lifestyle culture, if you put all those conversations next to each other, each person who listens to them is going to come up with their own response, aren't they? And that's just really valuable.

You interviewed some artists for the podcasts, but actually, when you think about it, there aren't that many artists in Cornwall who make art about Cornish identity or about Cornish history. It's a kind of blind spot. I've always made work that is connected to my Cornish identity, my relationship with the landscape in Cornwall and Cornwall's tangible and intangible heritage, and our built environment. It's just tangential in the way it comes out, because it's processed through me and my imagination. A lot of people have said to me 'Yeah, but you don't make work about Cornwall' but I have been making work about that experience the whole time! So maybe more people are making work in that way as well.

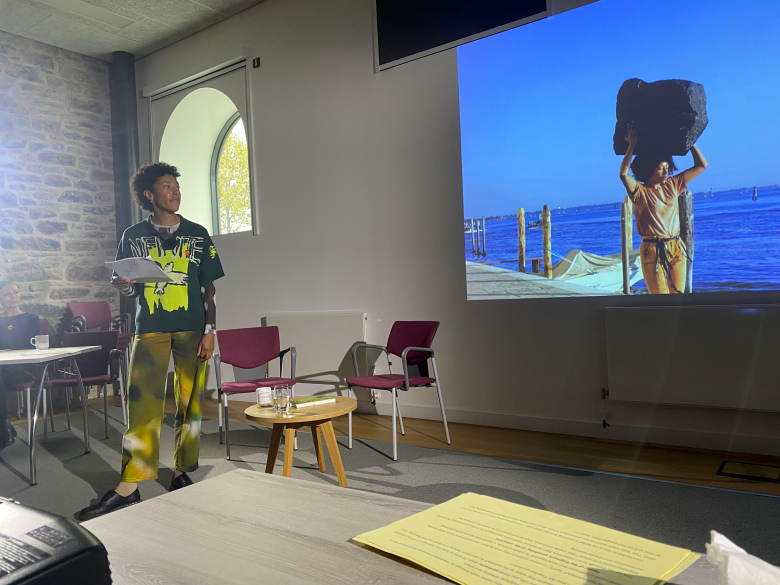

Just not in an overt, or obvious, way. Exactly. Take for instance, Libita Sibungu, so much of the work she was talking about is really connected to the experience of being Afro-Celt and growing up in Cornwall and her own personal experience. And then, in the podcast with Georgia Gendall and Liam Jolly, they both talk about their personal experience and they reflect back on their work and say, you know, these bits are about Cornwall, they are about my experience. And maybe as people who live and work here for a long time, it's not our role and responsibility to really obviously make work about Cornwall. We can just make work and then maybe there's bits of Cornwall in it.

Libita Sibungu speaking at the Meskla symposium

It was interesting hearing Georgia talk about her grandparents because several years ago I interviewed her grand-dad Richard Gendall for my book on folk music. Which reminds me, there's been renewed interest in Cornwall's folklore, witchcraft and sacred sites in recent years, and many artists and writers have been able to use that to bring Cornwall into their work. I'm really aware that I talk as a 50 year old artist now! But I've identified as a as a pagan since my teens, and the landscape of Cornwall and the standing stones and the mythology around how Carn Brea was formed, and all this stuff is utterly part of my being, and is completely within my work. But it goes back to that belief that it doesn't have to be explicit in the work. It's also very personal and intimate, and I don't necessarily feel like it's something I want to actively make work about at this moment. I'm also always really interested in the importance of mundane interactions with things. I was chatting with someone about this, who said, it's like the standing stones are their friends and family. And if I want to make fun of them, or just get drunk next to them or whatever, I can, but that doesn't mean I don't respect them, but I don't have to really explicitly revere them. The Merry Maidens to me, as a young girl, were really inspiring from a feminist perspective, they were radicalising to an extent: another thing that made me angry about the patriarchal establishment, but also recognising female power. I think for those artists who are explicit about that stuff its, like, great, but I'm very mindful of the sort of fetishes of the art world, and simplistic consumerism of the art world. And the spirituality and the import of all those sites and of magic, for want of a better word, is bigger than how the art world digests it.

It's been interesting following Ithell Colquhoun's revival on artcornwall, as she is very emblematic of that new way of thinking, that folklore-related notion of Cornish identity. I just want to say something about Ithell Colquhoun and, say, Barbara Hepworth. There is so much renewed reverence of these people from a feminist and queer perspective. But one of my interpretations of those artists is, that through a class perspective, they are very privileged individuals. And it concerns me when only very privileged individuals of a very particular era are so uplifted. I think this is what's important about Fran Rowse's work around elevating the bal maidens. I've always thought the women mending the nets in the Newlyn painter's paintings, they're also feminists. We don't need Virginia Woolf to happen to have an incredibly middle class lifestyle, to be a feminist. We don't need Barbara Hepworth, an incredibly privileged person, to be able to come here and be a feminist. You know, the women who are the true feminists are those who don't even have access to be elevated by the art world.

Fair enough! And Fran Rowse, who you mention, was part of the Meskla symposium at Kresen Kernow... So is Meskla finished now? Actually 2024 is the 10 year anniversary of the British government ratifying and identifying Cornwall as having national minority status, and I'm in conversation with other organisations to be doing things around that time. So the Meskla workshops will continue next year, but they might be in a different format. Iím currently developing plans and looking at fundraising.

MESKLA | Brewyon Drudh (Mussel Gathering | Precious Fragments) is an expanded sculpture project that took place in Redruth, Cornwall, between June & December 2022. This multi-platform art work used sculpture and conversation to explore contemporary Cornish cultural identity & its relationship with heritage, land and extraction industries.

https://sovayberriman.co.uk/MESKLA-Brewyon-Drudh

https://sovayberriman.co.uk/MESKLA-Symposium

4.12.22 |

|

|