|

|

| home | exhibitions | interviews | features | profiles | webprojects | archive |

|

Steve Patterson on Stonehenge, Starhawk and the Museum of Witchcraft In a second interview for artcornwall.org, folklorist and writer Steve Patterson reflects on the changing character of Neo-paganism in the post-war period, and the role of Cecil Williamson and the Museum of Witchcraft in Boscastle. Interviewer Rupert White.

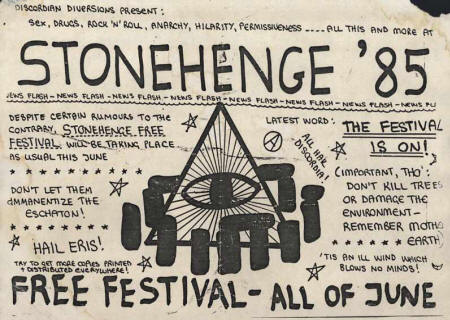

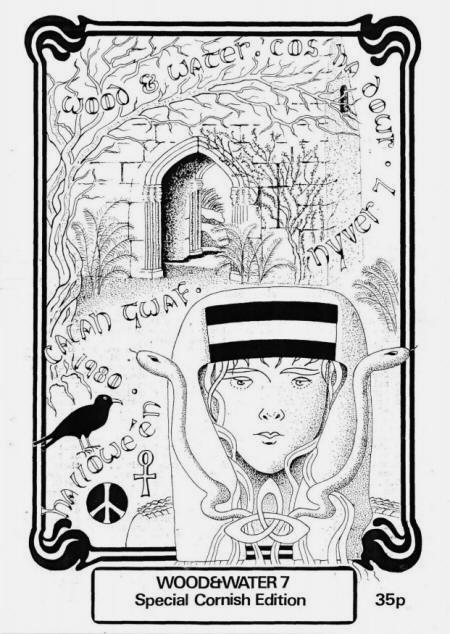

What is your background? What was your path to becoming a pagan? I was born 1965, so I was a teen of the eighties. I was brought up in a quiet village in the middle of Surrey. The eighties were very conservative. Thatcher was in full swing. The Greens were on the rise in Germany at the time, and there was a growing underground or counter-culture: ie interest in the Green movement; peace movement; sexual politics; gay rights; alternative housing; alternative education. Alongside these political ideologies, Paganism started developing as a theological element. In what way did it feel like a movement? How were people brought together? You’d come across like-minded people at the demos, the animal rights hunt sabs, CND meetings, peace camps and free festivals. Various mags were really important too then. Pipes of PAN; PAR (Pagan Animal Rights); Wood and Water; The Cauldron. Mike Howard (of The Cauldron) changed later, but early on he was a great supporter of left wing radical green politics. There’d been a weird transition. In the 50’s and 60’s Wicca was very much for the aspiring middle classes. Very conservative, with a big and little c. But there was a big change when it all got exported to the states. That’s when it got politicised. The voice that consolidated all of this was of course Starhawk. In ‘Spiral Dance’ she brought together magic and radical green feminist politics. These things hadn’t been bedfellows up to this point. That book was a game-changer. If you read Spiral Dance now, it seems a woolly and fluffy pagan thing, but at the time it was quite incredible. This was the end of the old school Wicca, the old initiatic covens. They still continued, but eco-feminism became the prevailing ideology through the eighties. And it was a big presence at the festivals and the peace camps. The other thing that was present at the festivals was a proto-shamanism - before it was called that - then it was the ‘Path of the Great Spirit’ or the ‘Red Road’. There were people in Tally in Wales; an alternative tipi community. They would have a tipi circle and talk openly about mother earth, and have sweat lodges. The difference between what they practiced, and shamanism now is that they were very aware of the native Americans’ rights. And so they were great supporters of Survival International and the Onaway Trust: they saw it as a political thing rather than a self-help therapy thing, which is what it morphed into. But it was seen as a kind of Paganism. Do you have strong memories of going to the festivals in the early 80’s - particularly Stonehenge? Yep. Definitely. I went to Stonehenge in '83 and '84 (picture above right). The police diverted everyone away from the festival in '85. Which lead to the 'Battle of the Beanfield'... Yes. As a lad I used to go round all the free festivals and the peace camps, and I’d take nothing but a blanket with me. I’d just rock up there and people had camp fires in the evenings and I’d always be taken in by someone. And on one occasion I was taken in by some people from Tally at Molesworth. And they talked about ideas to do with the Earth Mother and living in harmony with the land. And they talked about prana.

It was a basically a bender made of a willow and hazel dome, with a tarps over the top, and a sauna in it. They heated up the inside of this dome with hot stones, so I was inside and there were smudging ceremonies with burning sage, and they were all inside it chanting these prana chants, and a point came when I felt I was going to explode! And I had to get out. Everybody else was inside, it was full of nude bodies! But I crawled out of the heavy tarps and it was like crawling out of the womb. Two guys outside poured cold water over me, and my body seized up and I went into spasm, and I remember being on all fours and I was looking up at the stars and everything seemed so far away. I sniffed out my clothes in the darkness. In the morning I thought: ‘that was really strange’. But I realised that I had undergone some kind of transform-ation. For a several days afterwards I was walking about as if in a state of grace. I remember looking out over the Cambridgeshire fells and I could almost see this prana spiralling and moving. And looking back on it I had no language to explain it at the time, but it was a shamanic experience. Amazing. How old were you then? About 17. How did you end up in the South West? I had a year bumming around the festival and the peace camps then I moved to Plymouth to go to College. And there was a radical bookshop in Plymouth called ‘In Other Words’. They had a shelf on paganism, and books on Starhawk. The bookshops were key because this is where you’d meet people. How long were you in Plymouth for? I lived near Plymouth on the edge of the moors for about 10 years.

Jo O’Cleirigh had a stall he’d take around the fairs. He used to have pagan leaflets and Survival International leaflets, and CND leaflets. I’d been reading about Paganism but Jo introduced me more to the rituals and the practices. Jo used to describe The Regency rituals in Queen’s Wood: about how they were deeply symbolic, and they were held around a great old tree, and they broke away from the more verbose rituals of Wicca. He wrote for Wood & Water in the early 80’s (picture right). He did. I used to come down to Lamorna with Jo. That how I first came across Ithell Colqu-houn. She was still alive but I never got to meet her. And of course Starhawk herself came to stay with Jo in Lamorna. What else do you remember about your visits there? One of the ideas that Jo and I believe in is that paganism and the landscape are inextricably woven not in an abstract way but in a very actual way, and for Jo and I Lamorna is the hub. It’s linked to that very land. Another thing that came from the Regency is the use of the ‘stang’. Jo was one of the first I knew to use a stang, and call it that. Cochrane referred to a stang but was using it differently. Presumably you met Cassandra Latham? And she had her own coven… Yes. And she always leant more towards the Wiccan system. In West Penwith, early 90’s, you had Jo’s radical neo paganism; Cassandra was leaning more towards initiatic closed Wicca, but she was never a straight-down-the-line Wiccan: she again was drawing on more traditional old craft sources; then you’ve got Cheryl Straffon and the Earth Mysteries, which was seen as magical, pagan practice. And I believe in St Ives here was an absolutely traditional Gardnerian group. And then the Penwith Pagan Moot started in 94? Were you around then? I was around then. From the mid 80s I visited regularly, and moved down in mid 90’s. Adam Bear seems to have been the initiator of the moot. Interestingly Adam Bear came from that proto-shamanic, native American approach. That was his bag. I never met the guy. The moot thing is interesting. It’s part of this progression. In the 90’s it started to become formalised. You get the growth of the Pagan Federation and you get pagan publishing: suddenly in the 90’s you get more glossy magazines and lots more books. And you get the moots, which were promoted by the PF. There was a seachange, as in the 1980’s paganism was seen as a radical anti-state thing. Then in the 90’s it was ‘lets get this respectable and accepted’ and more mainstream. There was this sense that otherwise paganism would n’t survive. In the US paganism becomes an official religion. Moots became part of this. The moots brought together pagans of different persuasions. The term - I know it was a Roman word originally - but ‘paganism’ as we use it now seems to have come out of this time. The PF were representing all these different interests: they wanted an umbrella word. Can we talk about the Museum of Witchcraft, because Graham King took it over from Cecil Williamson (below left) in the mid 90’s. But what do you remember about it before then?

There was no library. It was like a sitting room. That was the flat where the manager lived? Yes. They had a live-in manager, but I have no idea who they were. Was there anything else resembling the library? Cecil Williamson always referred to the Witchcraft Research Centre. A lot of that would have just been in filing cabinets in his house which were destroyed when he died. When he died, his daughters wanted to clear out the house and a lot went on the bonfire. Lenkiewitz bought a lot of his stuff. Was Williamson’s museum a resource to pagans at all? It was a resource but not in the same way it is now. But it was still a resource that was much ignored. Wicca was the hegemony. It was all about Wicca and Cecil was sidelined and resentful about it. Like Ithell Colquhoun, he was quite isolated? Yes. But he was his own worst enemy. In his early letters he talks about having yearly gatherings but they never happened. There was no public resource. No meetings or talks or community like now. He talked about starting a study group, discussed with Ithell, but it never happened. When I first went to the museum in the early 80’s I’d never heard of it before. It was that unknown. Colin Wilson’s massive book on the Occult - 800 pages long – you’d have thought he would have visited and mentioned it. But he didn’t. Colin Wilson may not have even known about it. It was always unadvertised. You never knew if it was going to be open. But when I went to it I was blown away but it was very different. The Farrars weren’t writing about this! Cecil's narrative was so very different. I really struggled with it but I was intrigued by it. When Graham King bought it in 1996, he had a team of people to help. Cecil Williamson had done no structural work since he moved in he just got the artefacts up. So Graham wanted a team of people to strip out the cabinets pack everything and catalogue everything, and none of us had any experience we were making it up as we went along. You were still in Plymouth then. Where did you stay in Boscastle? We all used to pile into the living room and sleep in sleeping bags there. It was closed over the winter so we did it over the winter. There was a lot of dossing on the floor then. Cassandra was involved, but a lot of the others have disappeared over the years. Can you say more about Cecil’s ‘narrative’? When Cecil had the museum the narrative was all about the idea of wayside witch. Gardner was pagan ceremonial-based, based on the key ideas like Wheel of the Year, the God and the Goddess.

Gardner was drawing from European witch- trial accounts of the great Sabbats. Cecil Williamson was drawing from the British witch-trial accounts which were about familiars and no covens; solitary practitioners working in their communities. Much less spectacular. How did that change with Graham’s arrival? Graham had a new narrative. Cecil had said that it was tourist gold that kept the museum going. It was purely funded through door money. He had no interest in trying to appeal to witches. But Graham King was canny enough to know there was this growing pagan movement in the mid-nineties. He kept the spirit of what Williamson had in there, but he got rid of the dioramas and put in the Wise Woman’s Cottage, which is still drawing very much on Williamson’s idea of the wayside witch. Cecil said the dioramas were inspired by the Coven of Tanat. But we don’t know if the Tanats exist. He’s taken the secret about the Tanat to his grave. Ithell asked to be introduced to them, and Cecil wasn't pleased and that was the last correspondence and I think they fell out as a result. So Graham took Cecil’s narrative, and augmented it with an idea of Wicca that was going around in the 90’s, so you get a hybrid. Instead of being part of the tar babies exhibit, ‘Old Horny’ was presented as the male god of Wicca, for example? Cecil wouldn’t have done that. No. And the last room with ritual tools has also been added. So there was some acknowledgements of Wicca and other aspects of contemporary magical culture. Right up to when I wrote my book, Cecil was unknown and disregarded outside the museum. But now people talk about him in relation to traditional craft. Cecil has come very much back into the fold. Graham King saw what he was doing as running a business. But he had an enormous interest in the subject and he was influential in helping people widen their view away from Wicca.

There was a lot of energy in the 80’s when it was still a radical underground scene. Then, as it became institutionalised, it became more staid. As it came out in the open, some of the ‘magic’ began to dissipate. It’s like fairy gold, once you take that into daylight. It was like the moot thing. It was great a lot of ways that people were coming together, but the ‘magic’ definitely began to dissipate. I was giving a talk recently – we were talking about methods of transmission and there was a women who was saying ‘it’s all on the internet now. You can just look up spells on the internet now. You don’t need covens now’. It’s interesting that this seems the prevailing view. Which seems to relate to something you said earlier, when you were talking about Lamorna. It’s surely hard to separate landscape and witchcraft. Surely that’s where the magic comes from. When it only exists on the www it has no link to any place… It becomes a simulacra of magical ideas. Like my experience at Molesworth, magic is experiential and otherworldly. Unless you have that experience of otherworldliness, then you’re none-the-wiser, you think that what you see on the net is the real thing, and that whole hidden dimension remains hidden. The power comes from the folklore, and the traditions that link to the place? It should exist in a context and if you only take the visible bit its like only taking the tip of the iceberg. 1999 was the year of the solar eclipse. Cassandra and Andy Norfolk did a big ritual at Boscawen Un, and Oberon Zell was there too. It seems to have been a measure of how much things had changed since the 60’s Yes. The other big change mid 90's is that the internet gets switched on. And by the noughties the pagan world embraces the digital world, the old structures break up, the whole coven structure breaks up and whole ways of networking break up. And it’s a very different world from that point onwards. Eclipses are traditionally an inauspicious, dark time, and it was in accordance with that. It brought the worst out in many people. Took a long time to recover from it. May be it did mark the end of a particular stage of paganism in Britain. May be it marked the moment when it started turned in and became digitised and dissociated itself from the landscape

This interview was carried out in March 2017, as research for 'The Re-enchanted Landscape: Earth Mysteries, Paganism and Art in Cornwall 1950-2000' to be published in late 2017. |

|

|

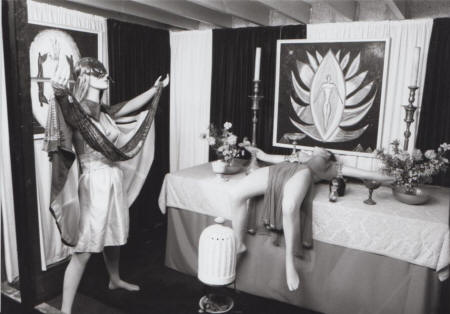

When

you went in there was a chicane and a dirty old bit of Perspex. There

was no shop. You went in and all the cabinets were waist-high concrete

blocks - no boutique lighting - it was an uncompromising assault on the

senses! There were two tableaux downstairs: the Temple of Tanat first

(below right), and then at the end there was the witches’ cradle. Then

upstairs was the tar babies and ‘Old Horny’ (below left), which was

glassed off like a diorama.

When

you went in there was a chicane and a dirty old bit of Perspex. There

was no shop. You went in and all the cabinets were waist-high concrete

blocks - no boutique lighting - it was an uncompromising assault on the

senses! There were two tableaux downstairs: the Temple of Tanat first

(below right), and then at the end there was the witches’ cradle. Then

upstairs was the tar babies and ‘Old Horny’ (below left), which was

glassed off like a diorama.