|

|

| home | features | exhibitions | interviews | profiles | webprojects | gazetteer | links | archive | forum |

|

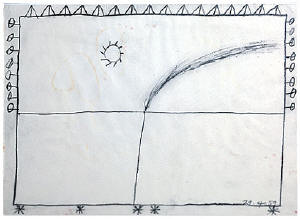

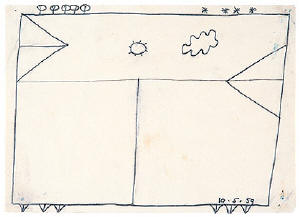

Bob LawBob Law started his life as a painter in Cornwall, and ended it there too. Included in the defining Tate exhibition ‘St Ives 1939 – 1964’ he is certainly part of the story of art from St Ives, but he is quite unlike any other artist that featured in the exhibition. This is because he was an uncompromising minimalist. Although he has been widely exhibited - and was described in his Guardian obituary as a ‘founding father of British Minimalism’ - he is not well known.

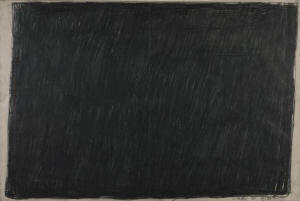

Whilst in Cornwall Law also started painting the monochrome all-black canvasses that he was to become famous for, and his big break came soon after when he was picked up by the critic Lawrence Alloway, and given a show in London at the new ICA in 1960. There followed one-man shows at

some of the most prestigious galleries across Europe, including Beuys’

gallery, Konrad Fischer, Dusseldorf (1970) and the increasingly

influential Lisson Gallery (1971). Later in the decade he had solo shows

at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (1974) – with a number of works

He continued his association

with the Lisson Gallery into the 80s and 90s, before moving back to

Cornwall in 1997. At the time of his retrospective at the Newlyn Gallery

in 1999, the Guggenheim Museum in New York were preparing a show of work

from the Panza Collection, which was to feature a prominent selection of

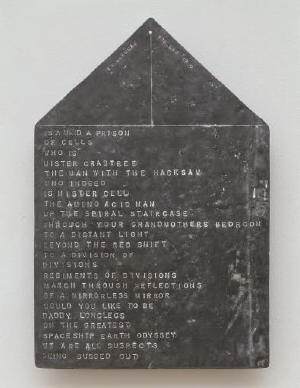

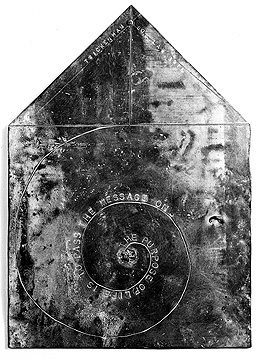

Law’s output. As with many of the better know minimalist artists, the minimalist label is constrictive and conceals more than it reveals. Like Carl Andre, Law wrote poetry and used text in a lot of his later work, and his sculptures often contained strong religious symbolism. The label is therefore a hindrance to understanding his art, which is difficult to place – certainly in relation to other artists with Cornish connections. His meteoric rise to art-world success was so breathtaking in its trajectory, that in some ways it overshadows the work itself, which is consistently quiet and understated. David Batchelor has claimed

that Cornwall appealed to artists in the 50s who wanted to escape the

autocratic influence of the post-war art schools, and in particular

conservative elements at the Slade. Being in Cornwall may have allowed Law

The more intriguing question for contemporary Cornish artists is how Law felt confident enough to resist the gestural, painterly influence of second-generation St Ives painters and embrace a hard-line minimalism: in the process going on to become the most widely exhibited artist of the ‘third generation’. It may be, simply, that his work, often angular and empty of colour always had a sobre, even melancholy quality, that was temperamentally at odds with the work of his other Cornish peers. Law died in Penzance in 2004.

http://www.artistboblaw.org.uk/

RW October 2006

|

|

|

to

be more receptive to American art – and, like other members of the St Ives

group, Law would have been well aware of artists like Ad Reinhardt who had

been painting large monochrome canvasses throughout the 50s.

to

be more receptive to American art – and, like other members of the St Ives

group, Law would have been well aware of artists like Ad Reinhardt who had

been painting large monochrome canvasses throughout the 50s.